This article is Lesson 22 of Andrew's book, Learn ClojureScript

This lesson has been a long time coming, and it is a critical one. By this point, we have seen that it is possible to write whole applications without using any mutable data, but for most cases, it is inconvenient to say the least. As we learned in the last lesson, ClojureScript encourages writing programs as a purely functional core surrounded by effectful code, and this incudes code that updates state. Being a pragmatic language, ClojureScript gives us several constructs for dealing with values that change over time.

In this lesson:

- Use atoms to manage values that change over time

- Observe and react to changes in state

- Use transients for high-performance mutations

Atoms

As we have seen many times, ClojureScript encourages us to write programs primarily as pure functions that transform immutable values. We have also seen that this can be somewhat cumbersome. Following the philosophy of pragmatism over purity, ClojureScript provides a convenient tool for representing state that changes over time: the atom. Atoms are containers that can hold a single immutable value at any point in time. However, the value that they refer to can be swapped out with another value. Moreover, our code can observe whenever these state swaps occur. This gives us a convenient way to deal with state that changes over time.

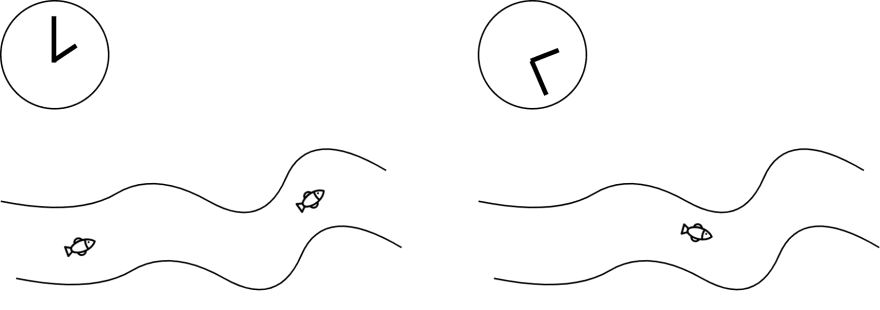

Unlike JavaScript, ClojureScript separates the ideas of identity and state1. An identity is a reference to a logical entity. That entity may change over time, but it still retains its identity in the same way that a river retains its identity even though it has different water flowing through it over the course of time. An identity may be associated with various values over the course of time, and these values are its state. Atoms are the state containers that we use in CloureScript to represent identities.

A River Has Many States Over Time

Updating state with swap!

The most trivial example of an identity that we can learn from is the lowly counter. A counter is an identity whose state is a number that increases over time. We can wrap any clojure value in an atom just by calling (atom v) where v is the value that becomes the atom's initial state:

(def counter (atom 0))

Since an atom provides a reference to some value at any point in time, we can dereference it - that is, get the immutable value to which it refers - by using the deref macro or its shorthand form, @.

counter ;; <1>

;; => #object[cljs.core.Atom {:val 0}]

(deref counter) ;; <2>

;; => 0

@counter ;; <3>

;; => 0

Dereferencing an Atom

- The atom itself is an object that wraps a value

- Atoms can be dereferenced with

deref - Prefixing an atom's name with

@is sugar for callingderef

Of course to be able to do anything useful with an atom we have to be able to update it's state, and we will use the swap! function to do this. swap! takes an atom and a transformation. That function will be given the atom's current state and should return its new state. swap! itself will return the atom's new state. Any additional arguments to swap! are passed as additional arguments to the transformation function. For our simple counter, we can use inc to increment it and + to add more than 1 at a time.

(swap! counter inc)

@counter

;; => 1

(swap! counter + 9)

@counter

;; => 10

Atoms are ClojureScript's way of providing a very controlled mechanism for updating state. When we dereference an atom, we still get an immutable value, and even if the atom's state is updated, the value that we received does not change:

(def creature

(atom {:type "water"

:life 50

:abilities ["swimming" "speed"]}))

(def base-creature @creature) ;; <1>

(swap! creature update :abilities conj "night vision")

@creature ;; <2>

;; => {:type "water"

;; :life 50

;; :abilities ["swimming" "speed" "night vision"]}

base-creature ;; <3>

;; => {:type "water"

;; :life 50

;; :abilities ["swimming", "speed"]}

- Dereference the atom before we

swap!in a new state - After the

swap!, the atom's state has changed - The initial state that we got is unchanged

We can also provide a function that acts as a validator that lets us define what sort of values are allowed in the atom using the set-validator! function2. The validator function takes what would be the new value of the atom. If it returns false (or throws an error), then our attempted update will fail and throw an error. For instance, to guarantee that we can never set a negative :life value on our creature, we could supply a validator to ensure this property:

(set-validator! creature

(fn [c] (>= (:life c) 0)))

(swap! creature assoc :life 10) ;; Ok

(swap! creature assoc :life -1) ;; Throws error

(:life @creature) ;; 10

As we just observed, updating the atom's state in a way that makes the validator return false results in an exception being thrown and no update being made. Validators are not commonly used in ClojureScript, but like pre- and post-conditions for functions, they can be a useful tool during development.

Quick Review

- What value does

swap!return? - How does a validator function indicate whether a state should be allowed or not?

Replacing state with reset!

While swap! is useful for transforming the state of an atom, sometimes we just want to update the atom's entire state at once. Using ClojureScript's standard library, this is not a difficult task: (swap! counter (constantly 0)). constantly returns a function that always returns a specific value every time it is called, so in this case, it returns a function that will always return 0, given any argument, which will effectively reset the counter state to 0. However, this code is not as cleat as it could be, which is why ClojureScript also provides the reset! function. This function simply takes the atom and a value, which it sets as the atom's new state. Like swap!, it returns the new state:

(reset! counter 0)

@counter

;; => 0

The reset! function is useful especially when we have some known initial state that we want to revert to, but otherwise, swap! is more commonly used in practice.

Observing Change with Watches

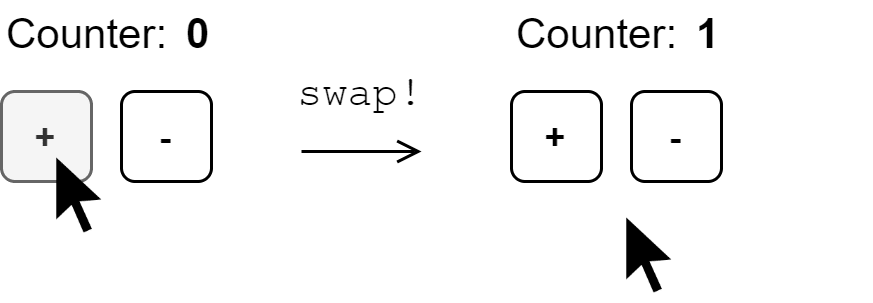

One of the most useful features of atoms is the ability to be notified whenever their state changes. This is accomplished with the add-watch function. This function takes 3 arguments: the atom to watch, a keyword that uniquely identifies the watcher, and a watch function. The watch function itself takes the keyword that was passed to add-watch, the atom itself, the atom's old state, and its new state. In most cases, the old and new state are the only things that we are interested in. To get our feet wet, let's implement a simple counter with buttons that can be used to add or subtract from its value.

Watching a Counter Atom

(defonce app-state (atom 0)) ;; <1>

(def app-container (gdom/getElement "app"))

(defn render [state] ;; <2>

(set! (.-innerHTML app-container)

(hiccups/html

[:div

[:p "Counter: " [:strong state]]

[:button {:id "up"} "+"]

[:button {:id "down"} "-"]])))

(defonce is-initialized?

(do

(gevents/listen (gdom/getElement "app") "click"

(fn [e]

(condp = (aget e "target" "id")

"up" (swap! app-state inc)

"down" (swap! app-state dec))))

(add-watch app-state :counter-observer ;; <3>

(fn [key atom old-val new-val]

(render new-val)))

(render @app-state)

true))

Counter Component

- Create an

atomto hold the counter state - Render takes the current state

- Add a watch function that re-renders the component whenever state changes

In this example, we use add-watch to observe changes to the state of the app-state atom. There is a related function, remove-watch, that can de-register the watch function. It takes the atom that is being observed and the keyword identifying the watcher to remove. If we wanted to remove the watcher in the example above, we could call this function like so:

(remove-watch app-state :counter-observer)

Challenge

Take the Contact Book app from Lesson 20 and refactor it to keep the state in an atom.

Transients

While atoms are the defacto tool for managing state that changes over time, transients come in handy when we need to introduce mutability for the sake of performance. If we need to perform many transformations in a row on a single data structure, ClojureScript's immutable data structures are not the most performant. Every time we perform a transformation of an immutable data structure, we create garbage that JavaScript's garbage collector will need to clean up. In cases like this, transients can be very useful.

A transient version of any vector, set, or map may be created with the transient function:

(transient {})

;; #object[cljs.core.TransientArrayMap]

The API for working with transients is similar to the standard collection API, but the transformation functions all have a ! appended, e.g. assoc!, conj!. The read API, however, is identical to that of immutable collections. A transient collection may be converted back to its persistent counterpart using the persistent! function:

(-> {}

transient ;; <1>

(assoc! :speed 12.3)

(assoc! :position [44, 29])

persistent!) ;; <2>

- Convert map to a transient

- Convert transient map back to a persistent (immutable) structure

Transients are not commonly used and should only be considered as a performance optimization when we have proven that a portion of code is too slow.

Using State Wisely

ClojureScript's state management - particularly atoms - give us great power to more naturally and intuitively model things that change over time, but with that power comes the potential of introducing anti-patterns. If we follow a couple of simple guidelines, we can ensure that our code remains clear and maintainable.

Guideline #1: Pass atoms explicitly

In order to keep a function testable and easy to reason about, we should always explicitly pass in any atom(s) on which it operates as arguments rather than operating on a global atom from its scope:

;; Don't do this

(def state (atom {:counter 0})) ;; <1>

(defn increment-counter []

(swap! state update :counter inc))

;; OK

(defn increment-counter [state] ;; <2>

(swap! state update :counter inc))

- Increment a global counter atom

- Increment a counter atom passed in as a parameter

While neither function is pure (they both have the side effect of mutating state), the second option is more testable and reusable because we can pass in any atom that we wish. We do not need to implicitly depend on the current global state.

Guideline #2: Prefer fewer atoms

In general, an application should have fewer atoms with more data rather than a separate atom for every piece of state. It is simpler to think about transitioning our entire app state one step at a time rather than synchronizing separate pieces of state:

;; Don't do this

(def account-a (atom 100)) ;; <1>

(def account-b (atom 100))

(swap! account-a - 25)

(swap! account-b + 25)

;; OK

(def accounts (atom {:a 100 ;; <2>

:b 100}))

(swap! accounts

(fn [accounts]

(-> accounts

(update :a - 25)

(update :b + 25))))

- Represent each piece of state as a separate atom

- Represent our "world" as an atom

While the second version is a bit more verbose, it has the advantage of creating cohesion between different steps that are all part of a "transaction", and it allows us to create complex state transitions without relying on many separate inputs. As we will see in the next section, this is also a common pattern when using the Reagent framework.

Summary

In this lesson, we were introduced to the critical feature of managing state that changes over time. As we have seen, we can create complete applications without resorting to mutability, adding just a small amount of controlled mutability can make our code dramatically simpler. We spent most of our time looking at how to use atoms to work with mutable state and how to observe and react to those state changes. We also looked briefly at transients - mutable version of ClojureScripts collections - and learned that while they are good for optimizing performance, they are not good general state containers. Finally, we looked at a couple of guidelines for constraining our use of mutable state that help make our applications maintainable and testable.

-

See https://clojure.org/about/state for a discussion on identity and state. ↩

-

Alternatively, a validator may be supplied when the atom is created by passing a map as a second argument to

atomwhere the:validatorkey points to the validator function:(atom init-val {:validator validator-fn})↩

Top comments (0)