I recently worked on an open source project called Jupiter, an online AI to beat the popular online game 2048.

Go try out the AI:

In writing this AI, I decided to use a machine learning method called the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm. Monte Carlo algorithms like the one used in Jupiter have been used in several notable AIs, including DeepMind's AlphaGo, which famously beat the Go world champion in May 2017.

In this article, I'll explain:

- How and why the Monte Carlo method works

- When and where Monte Carlo algorithms can be useful

- How I used the Monte Carlo method in an AI to beat 2048

- How to implement Monte Carlo algorithms in JavaScript and other languages

Note: I got the idea of using a Monte Carlo method to beat 2048 from this StackOverflow answer.

What is the Monte Carlo Method?

The Monte Carlo method is the idea of using a large number of random simulations of an experiment to gain insights into the experiment's end results. Random simulations of an experiment are frequently referred to as Monte Carlo simulations.

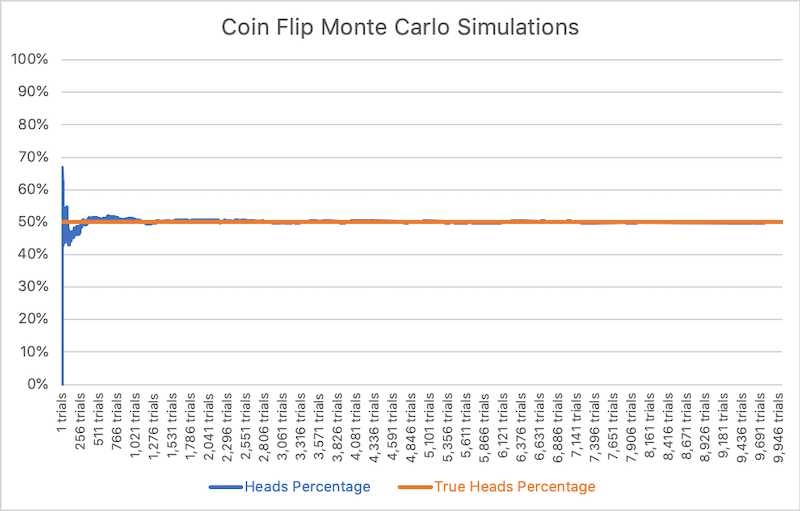

For example, let's say that you were flipping a coin, and trying to figure out the probability of the coin landing heads. With the Monte Carlo method, we could simulate 10,000 coin tosses, and calculate the percentage of coins that landed heads.

Here's what that would look like.

As can be seen, the result converges to the expected value, 50%. A notable feature of Monte Carlo simulations is that a higher number of simulations is correlated with higher accuracy. For example, if we only performed two simulations, there is a high (25%) probability of heads landing in both simulations, giving a result of 100%. This is very inaccurate in comparison to the expected result of 50%.

Monte Carlo simulations work because of the Law of Large Numbers, which says:

If you simulate the same experiment many times, the average of the results should converge to the expected value of the simulation.

In other words, Monte Carlo simulations are a way to estimate what will happen in a given experiment without having to implement any specific algorithms or heuristics.

When and Where the Monte Carlo Method Can Be Useful

The Monte Carlo method is used in a variety of fields, including game AI development, finance and economics, and evolutionary biology to name a few.

The Monte Carlo method can be useful in any experiment with a random factor, where end results cannot be predicted algorithmically. For example, in 2048, a new tile at a random location is added after every move, making it impossible to calculate the exact location of upcoming tiles and subsequently the end result of the game as well.

In these types of experiments, running a large number of Monte Carlo simulations can help get a sense of the average end results, the probability of various events occurring, and the relationship between the variables in the experiment.

For example, using the Monte Carlo method to in Jupiter allowed me to better understand how variables like starting move, number of moves in a game, and best tile in the board affected the end results of the game.

How I Used the Monte Carlo Method in Jupiter, an AI to Beat 2048

Let's start with a few definitions:

- Board and Tiles: a 4x4 grid with tiles optionally placed on each grid spot

- Game State: a set of tiles on the board which represents the board at a specific time

- Game Score: the sum of all the tiles on the board

- Real Game: the game that is being played and shown on the browser, not a simulation

At any given game state, let's assume that four possible moves can be made: left, right, up, or down.

There are indeed cases where a certain move is not possible in a given game state. Removing impossible moves can be easily added to the algorithm later.

With the Monte Carlo method, we can run a set of game simulations for every move.

For each possible move, the program simulates a set of simulations which start by playing the move for that set first. After that, the rest of the game can be played completely randomly until it is over.

In JavaScript, this algorithm looks something like:

// assume Game object exists

// assume currentGame variable exists as the real game

const totalSimulations = 200; // 50 simulations are played for each move

const possibleMoves = ["left", "right", "down", "up"];

possibleMoves.forEach((move) => { // simulations for all four possible starting moves

for(let i = 0; i < totalSimulations / 4; i++) {

const simulation = new Game(); // create simulation

simulation.board = currentGame.board; // copy current game state to simulation

simulation.makeMove(move); // make initial move

while(!simulation.gameover()) {

simulation.makeMove(possibleMoves[Math.floor(Math.random() * 4)]);

} // make random moves until simulation game is over

}

});

After all the simulations are completed, the program can gather the total final game scores of all the simulations, and average them for each move. We can then find the optimal move by optimizing for the highest final game score.

For example, if the simulations which started by playing left had an average final score of 250, whereas the ones which started by playing the other moves had an average final game score of 225, then left is the optimal move.

In this program, the optimal move is the one with simulations with the highest average final game score.

Note: I could have chosen to optimize for a different value such as the number of moves in the game.

However, this would actually make no difference in how the algorithm functions, because the number of moves in the game almost exactly predicts the game score. In 2048, the new tile added after each game move is normally a 2 tile, but has a 10% chance of being a 4 tile instead. This means the expected value of the new tile is 2.2 (

2 × 90% + 4 × 10%). The total value of tiles is also preserved after every tile combination (ex: 2 tile combined with another 2 tile gives a 4 tile). As a result, game score can be calculated by multiplying the expected value of the new tile by the number of moves in the game, or with this formula:2.2 × (real game move count + average move count).

To add this functionality of optimizing for highest score to our current code: add an array of total final scores for the simulations for each possible move, and choose the move with the highest value in that array to play like so:

const possibleMoves = ["left", "right", "down", "up"];

const totalSimulations = 200;

let moveSimulationTotalScores = [0, 0, 0, 0];

possibleMoves.forEach((move, moveIndex) => { // simulations for all four possible starting moves

for(let i = 0; i < totalSimulations / 4; i++) {

const simulation = new Game(); // create simulation

simulation.board = currentGame.board; // copy current game state to simulation

simulation.makeMove(move); // make initial move

while(!simulation.gameover()) {

simulation.makeMove(possibleMoves[Math.floor(Math.random() * 4)]);

} // make random moves until simulation game is over

moveSimulationTotalScores[moveIndex] += simulation.getScore();

}

});

// make best move with highest total simulation scores

let topScore = Math.max(...moveSimulationTotalScores);

let topScoreIndex = moveSimulationTotalScores.indexOf(topScore);

let bestMove = possibleMoves[topScoreIndex];

currentGame.makeMove(bestMove);

In the end, this algorithm is simple to implement given a well-written 2048 game class. In JavaScript, there are a number of performance upgrades that can be made, starting by adding concurrency with Web Workers and pruning moves with very low final game scores.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this post, and found it useful in helping you understand and implement the Monte Carlo method in your own projects.

Go check out Jupiter and its source code.

Thanks for scrolling.

— Gabriel Romualdo, September 12, 2020

Top comments (0)