An integer in Python is not a traditional 2, 4, or 8-byte implementation but rather it is implemented as an array of digits in base 2^30 which enables Python to support super long integers. Since there is no explicit limit on the size, working with integers in Python is extremely convenient as we can carry out operations on very long numbers without worrying about integer overflows. This convenience comes at a cost of allocation being expensive and trivial operations like addition, multiplication, division being inefficient.

Each integer in python is implemented as a C structure illustrated below.

struct _longobject {

...

Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt; // <--- holds reference count

...

Py_ssize_t ob_size; // <--- holds number of digits

digit ob_digit[1]; // <--- holds the digits in base 2^30

};

It is observed that smaller integers in the range -5 to 256, are used very frequently as compared to other longer integers and hence to gain performance benefit Python preallocates this range of integers during initialization and makes them singleton and hence every time a smaller integer value is referenced instead of allocating a new integer it passes the reference of the corresponding singleton.

Here is what Python's official documentation says about this preallocation

The current implementation keeps an array of integer objects for all integers between -5 and 256 when you create an int in that range you actually just get back a reference to the existing object.

In the CPython's source code this optimization can be traced in the macro IS_SMALL_INT and the function get_small_int in longobject.c. This way python saves a lot of space and computation for commonly used integers.

Verifying smaller integers are indeed a singleton

For a CPython implementation, the in-built id function returns the address of the object in memory. This means if the smaller integers are indeed singleton then the id function should return the same memory address for two instances of the same value while multiple instances of larger values should return different ones, and this is indeed what we observe

>>> x, y = 36, 36

>>> id(x) == id(y)

True

>>> x, y = 257, 257

>>> id(x) == id(y)

False

The singletons can also be seen in action during computations. In the example below, we reach the same target value 6 by performing two operations on three different numbers, 2, 4, and 10, and we see the id function returning the same memory reference in both the cases.

>>> a, b, c = 2, 4, 10

>>> x = a + b

>>> y = c - b

>>> id(x) == id(y)

True

Verifying if these integers are indeed referenced often

We have established that Python indeed is consuming smaller integers through their corresponding singleton instances, without reallocating them every time. Now we verify the hypothesis that Python indeed saves a bunch of allocations during its initialization through these singletons. We do this by checking the reference counts of each of the integer values.

Reference Counts

Reference count holds the number of different places there are that have a reference to the object. Every time an object is referenced the ob_refcnt, in its structure, is increased by 1, and when dereferenced the count is decreased by 1. When the reference count becomes 0 the object is garbage collected.

In order to get the current reference count of an object, we use the function getrefcount from the sys module.

>>> ref_count = sys.getrefcount(50)

11

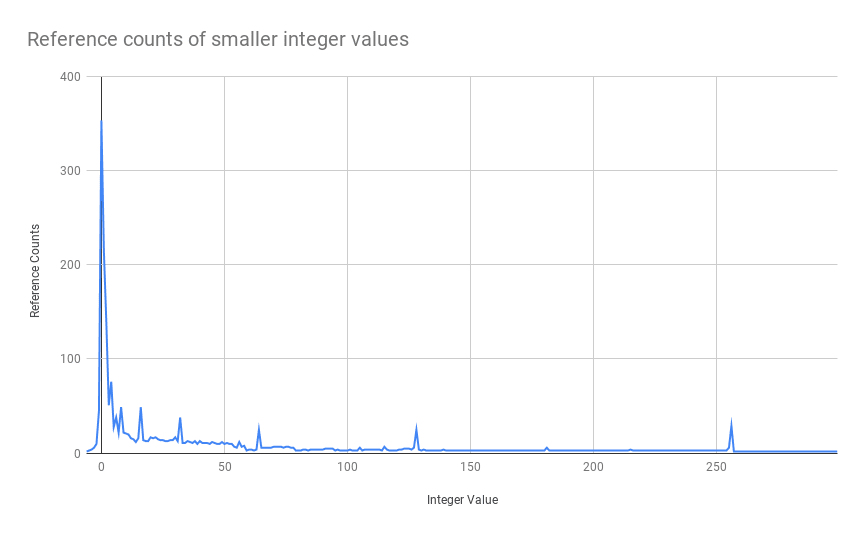

When we do this for all the integers in range -5 to 300 we get the following distribution

The above graph suggests that the reference count of smaller integer values is high indicating heavy usage and it decreases as the value increases which asserts the fact that there are many objects referencing smaller integer values as compared to larger ones during python initialization.

The value 0 is referenced the most - 359 times while along the long tail we see spikes in reference counts at powers of 2 i.e. 32, 64, 128, and 256. Python during its initialization itself requires small integer values and hence by creating singletons it saves about 1993 allocations.

The reference counts were computed on a freshly spun python which means during initialization it requires some integers for computations and these are facilitated by creating singleton instances of smaller values.

In usual programming, the smaller integer values are accessed much more frequently than larger ones, having singleton instances of these saves python a bunch of computation and allocations.

References

- Python Object Types and Reference Counts

- How python implements super-long integers

- Why Python is Slow: Looking Under the Hood

Other articles you may like

- Fractional Cascading - Speeding up Binary Searches

- Copy-on-Write Semantics

- What makes MySQL LRU cache scan resistant

- Building Finite State Machines with Python Coroutines

- Solving an age-old problem using Bayesian Average

This article was originally published on my blog - Python Caches Integers.

If you liked what you read, subscribe to my newsletter and get the post delivered directly to your inbox and give me a shout-out @arpit_bhayani.

Top comments (0)