In their most recent paper, researchers at DeepMind dissect the conventional wisdom that more complex models equal better performance.

The company has uncovered a previously untapped method of scaling large language models. To build effective language models, major tech companies like OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, Facebook, and even DeepMind are all missing the mark by making the models too large.

Kaplan and his colleagues at OpenAI established that, in 2020, a larger model is a stand-in for better performance. They found a power law correlation between those factors, leading them to conclude that as more resources become available to train models, the priority should shift toward making them bigger.

DeepMind’s findings will define language model scaling in the future

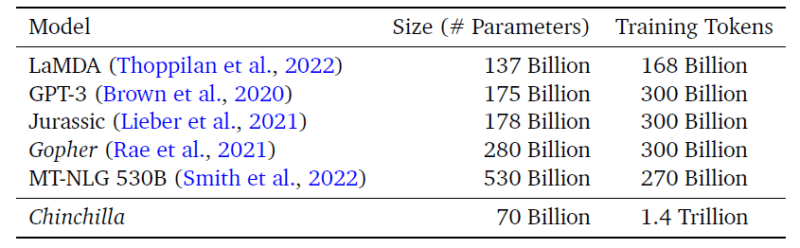

Since 2020, manufacturers have been steadily releasing bigger and bigger models like the GPT-3 (175B), LaMDA (137B), Jurassic-1 (178B), Megatron-Turing NLG (530B), and Gopher (280B). According to Kaplan’s law, these models are an improvement over their predecessors (GPT-2, BERT), but they still fall short of their full potential.

They erroneously concluded that increasing the size of the model was the only way to enhance it. They failed to take into account a key component: information.

In a new paper (“Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models” by Hoffmann et al. ), DeepMind researchers reexamined Kaplan’s findings and concluded that scaling the number of training tokens (i.e., the amount of text data fed into the model) is just as important as scaling model size.

Given a fixed compute budget, researchers should allocate it in similar proportions to increase model size and training token count in order to achieve the compute-optimal model (measured by minimal training loss) (measured by minimal training loss). In order to adequately train a large enough model, it is recommended that the number of training tokens be increased by a factor of two for each doubling of the model size. This means that a smaller model can significantly outperform a larger, but suboptimal, model if trained on a much larger number of tokens.

Also, they gave proof of it. The focus of the latest paper is Chinchilla, a 70B-parameter model trained on 4 times more data than the previous leader in language AI, Gopher (also built by DeepMind). According to the studies, Chinchilla is superior to other NLG systems like Gopher, GPT-3, Jurassic-1, and Megatron-Turing NLG.

The simple conclusion is that current large language models are “significantly undertrained” because researchers have been blindly following the scaling hypothesis.

Not only that, but also. Chinchilla’s reduced size makes inference and fine-tuning more affordable, opening up the possibility of using these models in settings where neither money nor cutting-edge hardware would otherwise be an obstacle. “The benefits of a better-trained smaller model extend beyond the immediate benefits of improved performance.”

Compute-optimal large language models

Compute budget is usually the limiting factor — known in advance and independent. Model size and number of training tokens are irremediably determined by the amount of money the company can spend on better hardware. To study how these variables affect performance, DeepMind’s researchers considered this question: “Given a fixed FLOPs budget, how should one trade-off model size and the number of training tokens?”

As stated above, models like GPT-3, Gopher, and MT-NLG follow the scaling laws devised by Kaplan (Table 1). To put a concrete example, if compute budget increases by a factor of 10, Kaplan’s law predicts optimal performance when model size is increased by 5.5x and the number of training tokens is increased by 1.8x.

Kaplan and colleagues arrived at this conclusion because they fixed the number of training tokens in their analysis. This assumption prevented them from finding DeepMind’s answer — that both model size and number of tokens should increase in parallel, roughly by 3.16x (or √10x).

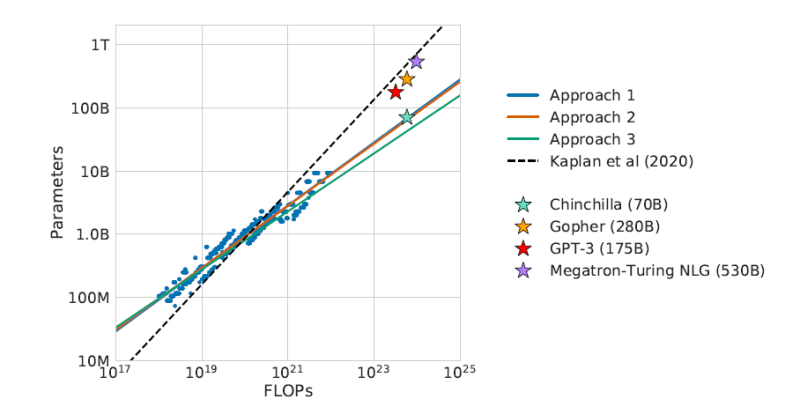

To study the relationship between compute budget, model size, and number of training tokens, researchers used three approaches (see section 3 of the paper for a more detailed explanation).

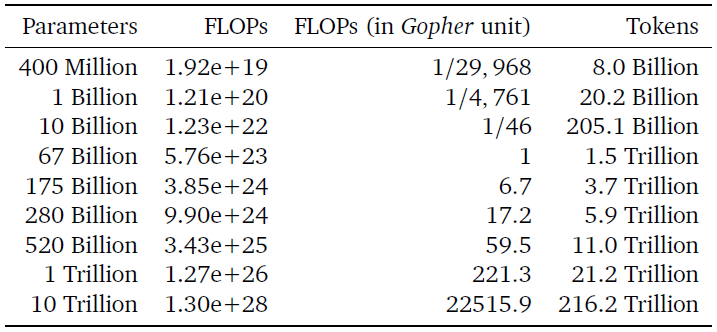

- Fixed model size: They defined a family of model sizes (70M-16B) and varied the number of training tokens (4 variations) for each model. Then they determined the optimal combination for each compute budget. Using this approach, a compute-optimal model trained with the same amount of compute as Gopher would have 67B params and 1.5T tokens.

- IsoFLOP curves: They fixed compute budget (9 variations ranging from 6×10¹⁸ to 3×10²¹) and explored model size (determining automatically number of tokens). Using this approach, a compute-optimal model trained with the same amount of compute as Gopher would have 63B params and 1.4T tokens.

- Fitting a parametric loss function: Using the results from approaches 1 and 2 they modeled the losses as parametric functions of model size and number of tokens. Using this approach, a compute-optimal model trained with the same amount of compute as Gopher would have 40B params.

In total, they evaluated over 400 models, ranging from 70M to 16B parameters and from 5B to 500B training tokens. All three approaches yielded similar predictions for optimal model size and number of training tokens — significantly different than that from Kaplan.

These findings suggest that models from the current generation are “considerably over-sized, given their respective compute budgets” (figure 1).

As it’s shown in table 3 (first approach), a 175B model (GPT-3-like) should be trained with a compute budget of 3.85×10²⁴ FLOPs and trained on 3.7T tokens (more than 10 times what OpenAI used for their GPT-3 175B model). A 280B model (Gopher-like) should be trained with 9.90×10²⁴ FLOPs and on 5.9T tokens (20 times what DeepMind used for Gopher).

They took the conservative estimates (approaches 1 & 2) to determine the size and number of training tokens of a compute-optimal model trained on the budget they used for Gopher. Chinchilla is the resulting model. 70B parameters, trained on 1.4T tokens (4x smaller and 4x more data than Gopher). Chinchilla outperformed Gopher — and all other previous language models — “uniformly and significantly.”

They proved their hypothesis: Increasing the number of training tokens at the same rate as model size provides the best results, other things being equal.

Results comparison: Chinchilla vs Gopher & Co

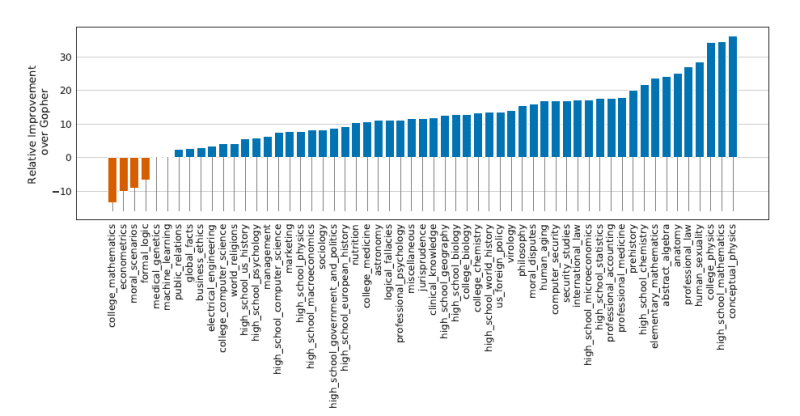

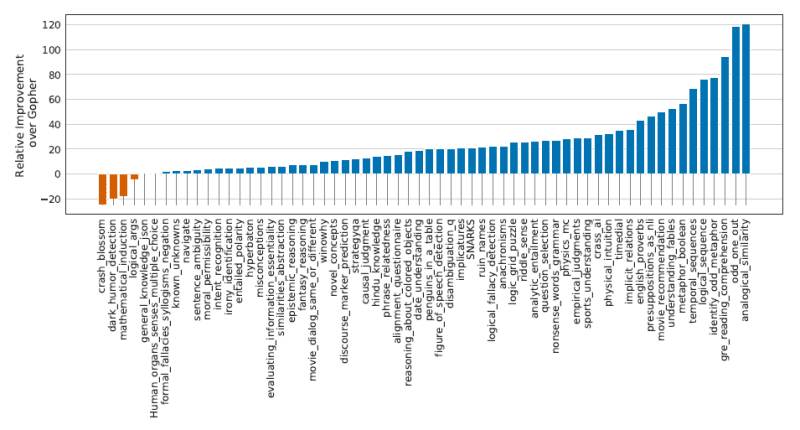

When we look at the results for each benchmark, saying Chinchilla outperformed Gopher feels like an understatement. To avoid cluttering the article with graphs, I’ll only show the results for Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU) and Big-bench (which account for 80% of the tasks) and ethics-related benchmarks — which always deserve special attention. (For a detailed analysis that includes reading, commonsense, and Q&A benchmarks, see section 4 of the paper.)

MMLU & BIG-bench

Chinchilla got new SOTA scores in both benchmarks. 67.6% average accuracy on MMLU and 65.1% average accuracy on BIG-bench, while Gopher got 60% and 54.4%, respectively (figures 2, 3). For MMLU, Chinchilla even surpasses the 63.4% mark established by experts as the predicted SOTA for June 2023. No one was expecting such an improvement so soon.

Chinchilla consistently outperforms previous LLMs in other benchmarks such as commonsense reasoning and reading comprehension, unquestionably claiming the language AI throne.

However, its hegemony was short-lived. Chinchilla was quickly surpassed by Google’s latest model, PaLM, just a week after its release (at 540B parameters it became the current largest and the most performant language model). This continuous chain of passings between companies exemplifies the field’s quick pace. Although Google did not fully incorporate DeepMind’s findings when developing PaLM, this was due to the fact that they were testing a different approach. (Look for a new article on PaLM soon!)

Gender bias and toxicity

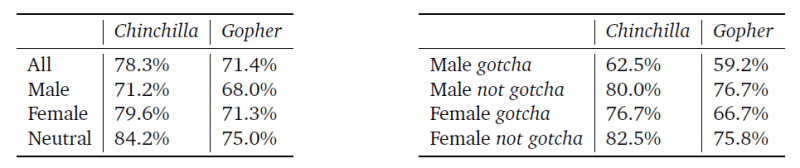

It’s expected that Chinchilla, which shares the same dataset and architecture as Gopher, will show similar behavior regarding bias and toxicity. It shows some improvements over Gopher in the Winogender dataset of gender and occupation bias (table 7), but not equally across groups.

In the PerspectiveAPI toxicity benchmark, Chinchilla and Gopher show similar results: “The large majority of generated samples are classified as non-toxic, and the difference between the models is negligible.” This also implies that, even if a model is trained on more data, it doesn’t necessarily get more toxic.

Hypothesis: How could they further improve Chinchilla performance-wise?

DeepMind discovered a new relationship between compute budget, model size, and training token count. However, these are not the only factors that influence performance and efficiency.

Finding the best hyperparameters is a major issue when training large models (HPs). Because current language models are so large, businesses can only afford to train them once: It is impossible to find the best set of HPs. To set them, researchers frequently have to make difficult – and frequently incorrect – assumptions.

Microsoft and OpenAI recently investigated a new type of parameterization (P) that scales well across different-size models of the same family. The best HPs from a smaller model can be transferred to the larger model, resulting in significantly better results.

DeepMind’s paper mentions previous work on hyperparameter tuning, but not this paper, which was published a few weeks ago. Using the optimal-compute paradigm in conjunction with the P should produce even better results for any large language model.

A retrieval mechanism could be another enhancement.

Despite being 25 times smaller, RETRO outperformed GPT-3 across all tasks. Because of its retrieval capabilities, the model was able to access a massive database (3T tokens) in real-time (In an analogous way to how we do internet searches).

Finally, if we wanted to take it a step further, an alignment technique could improve results not only in language benchmarks but also in real-world situations. With excellent performance results, OpenAI implemented a method to improve GPT-3 into InstructGPT. However, AI alignment is extremely complex, and InstructGPT does not appear to improve in terms of safety or toxicity over previous models.

If a company combined all of these features into a single model, they would create the best overall model possible based on what we know now about large language models.

Four critical reflections from Chinchilla

A new trend

Chinchilla’s performance is impressive not only because of the magnitude of improvement, but also because the model is smaller than all large language models developed in the last two years that demonstrated SOTA performance. Instead of focusing on increasing the size of the models, as many AI experts have suggested, companies and researchers should optimize the resources and parameters they have — otherwise, they are wasting their money.

Chinchilla is a game changer in terms of both performance and efficiency.

Because Google’s PaLM has achieved SOTA results in many benchmarks, Chinchilla’s performance is no longer the best in the field. However, Chinchilla’s main influence comes from being extremely good while breaking the pattern of making models larger and larger.

The ramifications of this will shape the field’s future. To begin, businesses should recognize that model size is only one of many variables that affect performance. Second, it may dampen public expectations of ever-larger models in the future, as a sign that we’re getting closer to AGI much faster than we actually are. Finally, it may help reduce the environmental impact of large models as well as the barriers to entry for smaller companies that cannot keep up with big Tech.

This brings me to my second point of reflection.

Limited reproducibility

Chinchilla is a small model, but it is still too unusual for most businesses and schools to devote resources to its training or study. No one describing a 70B as “small” can possibly be unaware of the implications of this statement. Those who would benefit most from studying these models (researchers) typically lack the financial means to conduct the necessary experiments. As a result, modern AI is precariously supported by a small group of powerful companies that set the research agenda.

But there’s another, non-monetary barrier to progress as well.

Chinchilla is unlikely to be made public by DeepMind. Both Google and OpenAI have stated that they have no plans to release their respective deep learning libraries anytime soon. In many cases, the publication of such models serves only to showcase who is at the forefront of the field, rather than to facilitate further study. Although DeepMind is one of the AI companies that has done the most to advance science and research by sharing its discoveries (they made AlphaFold predictions freely available), the culture of showing off is still pervasive in the industry as a whole.

By creating a more effective and compact model, DeepMind hopes to buck a downward trend. Nonetheless, we should take pride in how far we’ve come in democratizing a technology that will reshape our future, especially since Chinchilla is still a major model. Building an AGI will be pointless if we continue down the current path of a select few controlling the funding, focus, and outcomes of scientific research.

Data audit

The training of current models is inadequate (or oversized). In order to construct optimal-compute models, businesses will require more extensive datasets than they typically have access to. Large, high-quality text datasets will be in demand in the near future.

Professor of linguistics at the University of Washington Emily M. Bender criticized Google’s approach to PaLM, saying that the model is “too big to deploy safely” because it uses 780B tokens of data for training without adequate documentation. More tokens were used to train Chinchilla. Since Bender’s criticisms can be extrapolated to Chinchilla (depending on the process DeepMind used to train the model), we can conclude that it is also not safe to deploy.

To enhance models while keeping them compact, more data is required. However, the models’ safety decreases as more data is used. Models can either be made bigger (out of reach for most players on the field and increasing their carbon footprint) or trained on more tokens, but this comes at a cost (i.e. making data audits harder and the models less safe). It’s no longer a fair comparison to say that Chinchilla is better just because it’s smaller.

It’s also possible to divert resources to other research avenues that don’t necessitate the use of huge datasets for training models. Since only Big Tech can afford to pursue the research avenues they find most promising, only those avenues yield results; not because other avenues can’t work, but because they aren’t being pursued to their full potential.

Inherent bias

It seems that it doesn’t matter how much researchers optimize models in terms of performance or efficiency, they can’t seem to reach acceptable levels of bias and toxicity. Transformer-based large language models may be inherently subjected to these issues, regardless of model size, dataset size, hyperparameter quality, compute budget, etc.

We won’t solve the ethical issues of language models simply by making them better at performance benchmarks.

Top comments (0)