Background

At Deta, we believe the individual developer should be empowered to create their own tools in the cloud. We also see that the tools for building these tools are more approachable than ever. What follows is a description of building my own tool, Yarc, to demonstrate this and to scratch an itch within my own workflow.

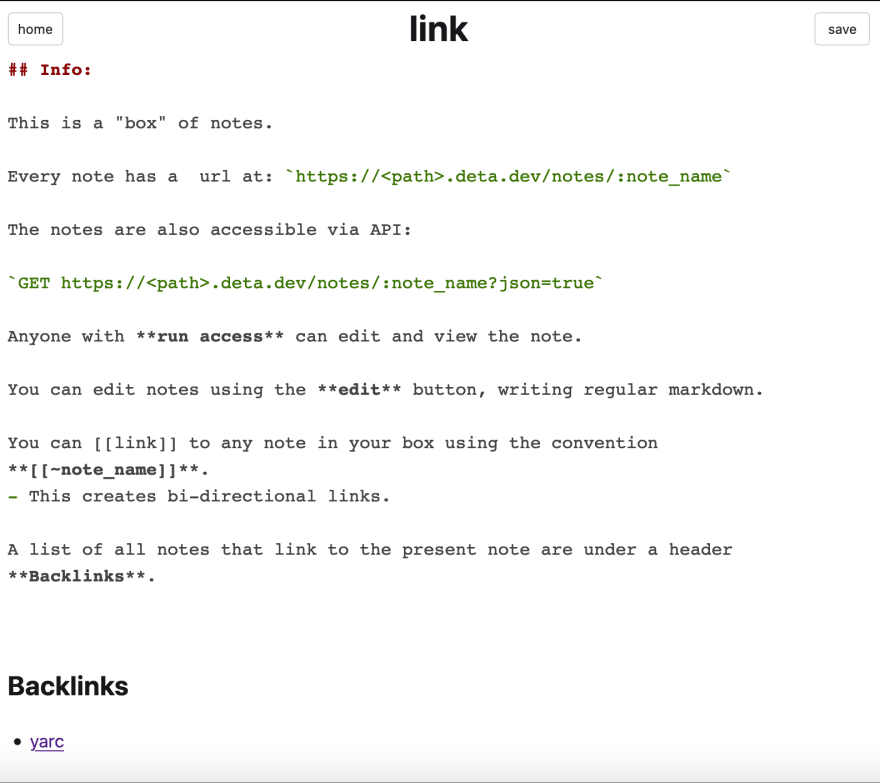

Roam Research is a notes app which describes itself as a 'tool for networked thought'. Roam aims to free your notes from a rigid hierarchical structure (what they call 'the file cabinet approach') in tools like Evernote. Using Roam, one can easily and deeply network notes using advanced hyperlinking capabilities. For instance, in any given note, one can see all the other notes (backlinks) which link to the said note (bi-directional linking).

I personally liked the bi-directional linking in Roam, but I wanted something lighter weight with the ability to open up the hood and add features as I saw fit, like accessing the raw text of my notes over API. I saw many other permutations of tools that had offered their own take on the bi-directional linking in Roam (see Obsidian, Foam); I named my own clone Yarc (yet another roam clone).

With Yarc, I'm not declaring that this project comes remotely close to matching what the team at Roam has done. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and Roam offers far more advanced capabilities than Yarc will likely every have.

Project Design

What I needed was for the app was simple, consisting of three significant parts:

- Core Functionality: a standard for writing notes, uniquely addressing them, and bi-directionally linking them

- Backend: the backend needed to serve a note and its contents as well as process updates (content, links, and backlinks) to a given note

- Frontend: a client / UI to easily view and update the notes

Core Functionality

First, for the notes themselves, I decided to use Markdown as it is a standard with a syntax versatile enough to support text documents with code snippets, hyper links, pictures, etc, built-in. There is tremendous support for Markdown across many tools, some of which I use in Yarc; if I ever need to migrate any notes out of Yarc, there shouldn't be major conflicts using other tools.

The basic feature in Roam I wanted to emulate was the ability to bi-directionally link notes, triggered by the indicator [[]]. For example, if Note A includes text: bla bla [[Note B]], then Note A should link to Note B, and Note B should have Note A in its list of Backlinks. For this to work, I needed two things:

- each note needs a unique address tied to a name

- a way to process

[[name]]tags as links to that address

The principle which drives Yarc follows from recognizing that Markdown and HTML provide great support for HTTP links out of the box. Consequently, I could give each note a unique HTTP address (e.g: :base_url/notes/:note_name ) and prior to rendering a Markdown note as HTML, pre-process [[note_name]] links by converting them to traditional markdown links [note_name](:base_url/notes/:note_name), while also keeping track of all backlinks in the backend.

To recognize all the unique [[]] links in a markdown note, I wrote a short JavaScript function with a bit of regex that spits out the set of unique [[]] links. When we save a note, we can tell our backend to add the current note as a backlink to all the unique links in the current note.

const getUniqueLinks = rawMD => {

const uniqueLinks = [...new Set(rawMD.match(/\[\[(.*?)\]]/g))];

return uniqueLinks;

};

Additionally, we can use the array of current links to create the substitution from a [[]] link to a normal Markdown link ([]()) prior to converting the Markdown to HTML.

This function takes our unique Markdown with [[]] tags and spits out standard Markdown:

const linkSub = (rawMD, links, baseUrl) => {

let newMD = rawMD;

for (const each of links) {

let replacement;

const bareName = each.substring(2, each.length - 2);

replacement = `[${bareName}](${baseUrl}notes/${encodeURI(bareName)})`;

newMD = newMD.split(each).join(replacement);

}

return newMD;

};

These two functions form the core of Yarc: recognizing the set of bi-directional links in a note and converting the syntax we use into regular Markdown (which can be converted to HTML). Everything else is tying the database, routes, and UI together.

Backend: Deta + FastAPI + Jinja2

For the backend I used:

- Deta to host the compute + api and database

- FastAPI as the web framework to do the heavy lifting

- Jinja2 to generate the note templates to serve to the client

Database (Deta Base)

I used Deta Base to store permanent data. The database operations are in the note.py file and handle reading and writing the raw note data. The basic data schema for a note is stored under a key (which is the urlsafe version of a note's name), and has the following fields:

name: str

content: str

links: list = []

backlinks: list = []

Routing and Main Functionality (FastAPI on a Deta Micro)

I used Deta Micros to run the FastAPI application and host it at a unique URL. The routes and business logic for the application are built using FastAPI and are in main.py. FastAPI describes itself as a 'micro framework' and their philosophy of sane defaults and a low learning curve were great in contributing to a quick process of building Yarc. If you know Python, building a web app with FastAPI is a very straightforward process.

There are three primary routes & functionalities in Yarc's backend:

-

GET /: returns the homepage -

GET /notes/{note_name}: returns a note with a given name (and creates the note first if it doesn't exist). Accepts an optional query parameterjson=truewhich returns the note information as JSON. -

PUT /{note_name}: receives a note payload, updates the database entry of a given note and all other notes that the note links to (as the backlinks fields need to be updated).

This third route, which keeps track of the correct links & backlinks across notes, was the most involved piece, so I'll include this operation here:

@app.put("/{note_name}")

async def add_note(new_note: Note):

old_note = get_note(new_note.name)

old_links = old_note.links if old_note else []

removed_links = list_diff(old_links, new_note.links)

added_links = list_diff(new_note.links, old_links)

for each in removed_links:

remove_backlink(each, new_note.name)

db_update_note(new_note)

for each in added_links:

add_backlink_or_create(each, new_note.name)

return {"message": "success"}

Templating

To serve the notes I used Jinja2 to template HTML files with the note data and the frontend JavaScript code, written in Hyperapp. By injecting the frontend JavaScript into the template instead of importing it as a module, I saved one API call on every page load.

Libraries Used:

Frontend: Hyperapp

For the client side of the web app I used (and learned) Hyperapp. Hyperapp is a super lightweight (1kb, no build step!) framework for building interactive applications in a functional, declarative manner. Having experience using React (+ Redux) where a Component combines state management, a description of the DOM, and side effects, I'd say Hyperapp more clearly de-lineates their concepts (views, actions, effects, and subscriptions). As with other frameworks, there's a bit of a learning to get familiar with their concepts, but once you get a handle on them, it is a joy to work with. Like FastAPI, it lives up to its name, and you can build and ship useful applications super quickly.

For interacting with a note (code in note.js), the Hyperapp application has two primary 'modes' as an end user (toggled by triggering a Hyperapp action):

- Edit Mode: This mode displays the raw markdown of a note, allowing the user to write notes

- View Mode: This mode displays the note as HTML, allowing the user to follow links

Edit Mode

Editing mode is triggered when the user clicks the edit button, which dispatches the Edit action in Hyperapp. This action also triggers an effect, attachCodeJar, which attaches the text editor I used, CodeJar, to the correct DOM element and binds another action, UpdateContent, to the text editor such that the current state of the text editor is saved into the state tree in Hyperapp.

// Edit Action

const Edit = state => {

const newState = {

...state,

view: "EDIT"

};

return [newState,

[attachCodeJar, { state: newState, UpdateContent }]

];

};

// attachCodeJar Effect

const attachCodeJar = (dispatch, options) => {

requestAnimationFrame(() => {

var container = document.getElementById("container");

container.classList.add("markdown");

const highlight = editor => {

editor.textContent = editor.textContent;

hljs.highlightBlock(editor);

};

jar = CodeJar(container, highlight);

jar.updateCode(options.state.note.content);

jar.onUpdate(code =>

dispatch(options.UpdateContent(options.state, code))

);

});

};

// UpdateContent Action

const UpdateContent = (state, newContent) => {

return {

...state,

note: {

...state.note,

content: newContent

}

};

};

View Mode

View Mode is triggered by clicking the save button, which dispatches the Save action in Hyperapp and triggers two effects: attachMarkdown and updateDatabase.

- attachMarkdown removes the text editor from the DOM element and replaces it with the HTML output from converting the latest note Markdown in state using Showdown.

- updateDatabase sends the latest note Markdown, links, and backlinks to the backend to save in the database, via an API call.

Libraries Used for the Frontend

Summary

The full source code of the project is here and includes other bits of the application like the homepage, searching, and interacting with the notes over CLI. It also provides instructions for deployment on Deta if you want to deploy your own instance of Yarc.

There are a number of great tools out there that let you build your own cloud tools remarkably quickly, with little overhead. At Deta, we try to provide no-fuss infrastructure to get your code running. I personally found both FastAPI (for the server) and Hyperapp (for the client) to be really complementary frameworks for building lightweight, personal apps; both are great, no-fuss, options that provide a lighting quick route to getting something out.

Top comments (0)