Editorial Note: this post is part of my SEO for Non-Scumbags series, which I began here.

So far in this SEO for non-scumbags series (first post and index here), I’ve spent two posts making the case for SEO to a skeptical audience and laying some strategic groundwork. Now it’s time to talk specifics and move to the more tactical.

In this post I’m going to cover what I consider the most crucial aspect of SEO, but one that people largely ignore in favor of stats about keywords. I’m going to talk searcher psychology. Specifically, I’ll talk through which keywords you’d want to tackle and why.

What is a Keyword?

First, though, some housekeeping. The word “keyword” sees a lot of play in SEO circles, but what, exactly, do we mean by keyword?

That part is simple. A keyword is the term that someone types into the search engine (or URL bar) when executing a search.

And, let’s define another term while we’re at it. The SERP (search engine results page) generally refers to the resultant page from that search — specifically the first page.

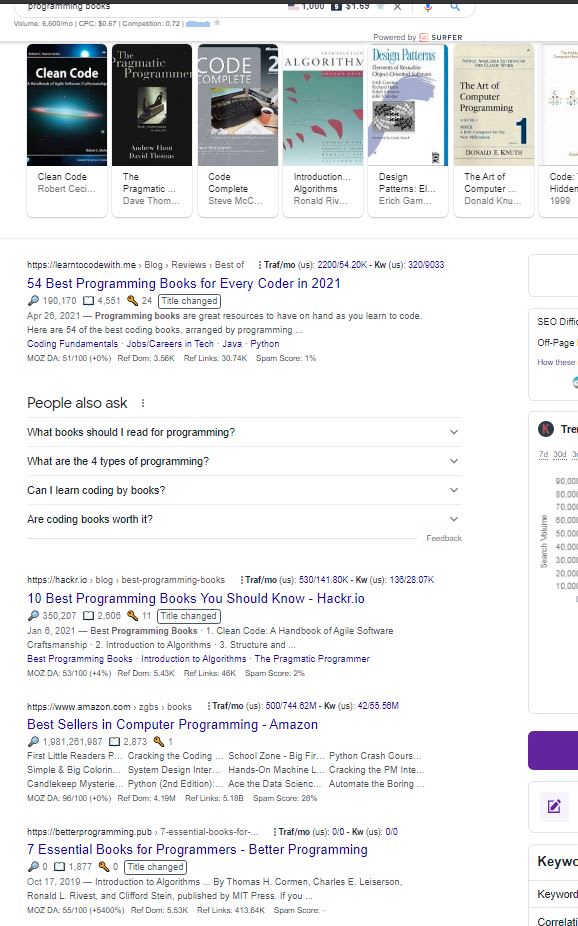

Putting these together, the goal with SEO (whether the traditional “search engine optimization” or my preferred co-opting of “searcher experience optimization”) is to “target” a keyword in such a way that you become the top entry in the SERP. In the case of the screenshots, we’d look to unseat learntocodewith.me as the first thing to appear when someone searched “programming books.”

What Keywords Really Are: Questions

Alright, with the absolute beginner stuff out of the way, let’s look at important stuff most SEO tutorials gloss over or ignore altogether.

A keyword isn’t just the words that the searcher types into the search engine. To appropriate a witticism from the world of jazz, a keyword is, in a sense, the words that the searcher _doesn’t _type into the search engine. I say this because keywords are always full blown questions in the mind of the searcher.

What Are Some Programming Books?

Take, for instance, “programming books” as a keyword. The _real _keyword is “what are some programming books” or, perhaps, “what are the best programming books?”

Don’t believe me? Consider the search results in more detail:

Once you scroll past the gigantic carousel showing the searcher lots of books, you see 4 pieces of content that feature lists of books, sandwiched around a “people also ask” widget where the search engine freakin’ tells you that people ask the question “what books should I read for programming?”

What is Value Stream Mapping?

If you want to see another example, consider this one from the wild. This is from our actual work history, and a moonshot at ranking for an extremely difficult term: value stream mapping.

When you see Wikipedia as the top entry, there's a pretty good chance the searcher is asking "what does X mean?" But, in case that's not compelling enough for you, consider the people also ask of "what is value stream mapping" or the title of the asq.org article on the topic: "what is it?"

We actually wrote a definitional guide to value stream mapping for Plutora, which generally sits at or near the front page. That's normally not a rank I'd be in love with, but for a "what is it" search, going toe-to-toe with Wiki and edu sites, that's no small feat. And it certainly means we're getting the searcher question right.

Answer Searchers' Questions!

Divining people’s actual question — the _real _keyword — is thus utterly essential for ranking. It’s more important than volume, difficulty, or all of the billion pieces of technical minutiae SEO tips, and it’s not close.

Understand their question, and rank. Get it wrong, and forget it.

If you want to win the search “programming books,” you’ll win with a helpful list of career-spanning programming books. You’ll lose if you target the keyword with a clever hot take like “Programming Books Reconsidered in 2021.”

Do you know why? Because nobody on the internet is asking what you think about programming books in 2021, even if both their question and your premise happen to contain the words “programming books.”

The Idea of Searcher or Search Intent

So far, I’ve presented you in this post with what I’ll grandiosely call “Erik-theory” of SEO. Let’s anchor a little with wisdom from outside sources, to give you at least a little “you are here” sanity in the world of other SEO tutorials you might read.

If you go read about something called search intent (Yoast’s definition is as good as any), you’ll find a list of four broad types. That is, there are four loose buckets of things that people are trying to accomplish. Here are my quick definitions:

- Informational search intent : people are doing some kind of research (looking up a definition, searching for a tutorial, asking for directions, etc.)

- Transactional search intent : people are looking to buy something right now (e.g. searches for “light bulbs” or “otter box replacement galaxy s10.”)

- Commercial search intent : people are researching and evaluating a potential purchase, which they may or may not later make online (e.g. “best lawnmowers 2021” or “APM tools”).

- Navigational search intent : people are just using the search engine to avoid typing the full URL of something (e.g. “etsy” when they want to go to etsy.com).

This is definitely a helpful and well thought out framework. But understand that it’s helpful for general SEO pros, more than it is for Hit Subscribe technical account strategists (and presumably most of you reading). Those SEO folks, after all, are likely to have clients in the eCommerce space, among others.

A More Precise Definition of Search Intent

For most of the readers, transactional and navigational intents are entirely irrelevant, and commercial intent is mostly irrelevant. (Commercial and informational bleed together, so it’s relevant where it borders informational). We are then left with the relatively unhelpful framework of “everything we care about is mostly informational!”

We then need to go deeper than calling everything “informational” search intent. That’s why our internal briefing system has much more precision for what we call search intent.

Our version is to actually completely elaborate the question that the searcher is asking when they type this term. So we think of the search intent for the keyword “programming books” not as “informational” but rather “what are some programming books?”

Multiple Questions, Fragmented Search Intent

At this point, you’re probably asking the question that I’d be asking if I were you.

How do you know that different people typing the same keyword aren’t asking different questions?

Good question, hypothetical second party. I’m glad you asked.

This has a lot to do with a concept called “short tail” and “long tail” keywords, which I’ll get into in depth in post 5 in the series. But for now, let’s just say that this varies by keyword. With some keywords (especially when you’ve done this for a long time) you can easily tell what question most or all people are asking, and with others, it’s anyone’s guess.

When it’s anyone’s guess, we have what I think of as fragmented search intent. For instance, take the word candle. If someone types “candle” into the search engine, they could be asking all kinds of questions:

- Where can I buy a candle online?

- What candle stores are nearby me?

- I’m new to English, what does “candle” mean?

- What was that Yankee whatever candle store or something?

You don’t know what they mean, and neither does google. At the time of writing, executing this search resulted in Yankee Candle’s website, a “candle stores near you” widget, a “buy candles online widget,” and the Wikipedia entry for candle, among other things.

We Generally Avoid Fragmented Search Intent

In this series’ very first post, I talked about SEO really being Q&A, writ large, across the entire internet. People are asking questions (albeit abbreviated ones), and we’re seeking to answer them.

What, then, do we do when we find fragmented search intent? Should we create some monstrous piece of content that addresses all possible questions? Should we write “The Ultimate Candle Guide,” and include a definition of candle, recommendations for online shopping, recommendations for local shopping in major cities, candle reviews and more?

Nope, don’t do that. Ignore the keyword instead.

Someone looking for a quick definition of the word isn’t interested in shopping (research vs. transactional intent). And someone interested in shopping will be supremely annoyed at having to scroll past a superfluous definition of the word candle. Think of the ancient proverb:

If you chase two rabbits, you will lose them both.

So ignore that vague keyword (even if it has monstrous volume and low difficulty, which we’ll address in the next installment). Instead, look for keywords containing it that lend more specificity to the search, so that you’re clearer what question the searcher might be asking. Those might include “candles on sale” or “candle meaning,” for instance.

Understanding Goals and Moods of Searchers

I don’t really know why we like to Tarzan search engines, instead of saying or speaking full queries. Perhaps it’s just a function of how we learned to interact with them, or maybe it’s that we really like to save the 2 seconds of typing. I’m not a historical internet anthropologist.

But whatever the reason, just about everyone does it. Google searches are, by and large, so focused and so tactical that searchers don’t want to type even 2-3 extra words if they can avoid it.

And that brings me to another important point about searcher psychology.

People with specific, tactical questions are ruthless with their attention. Anyone googling “garlic chicken recipe” does NOT want to read a long backstory about you cooking with your grandmother. And anyone googling “programming books” does NOT want to read about your opinions about the industry.

At best, they’ll tolerate those things, and at worst, they’ll smash the back button.

When you think of this through the lens of searchers asking specific questions, this makes sense. Imagine this conversation:

Friend : What’s a good recipe for garlic chicken?

You : Let me tell you a tale about my grandmother and I, cooking together in a bucolic setting 30 years ago…

Friend : Unsubscribe.

When someone asks the search engine a question, they are laser-focused on finding a quick answer. They will look critically at your title and description on the search results page, trying to determine if you’ll answer their question. When they click, they’ll quickly scan the article through the same skeptical lens.

Only after assuring themselves that you won’t waste their time will they begin to engage. And then only really insofar as getting an answer to their questions.

Winning with Response Posts

You can understand, then, a significant correlation between identifying specific questions from keywords, answering those questions and good searcher experience. All of those things, then, translate into you ranking and earning traffic.

Make the searchers happy, you’ll be happy. More specificity makes both of you happy.

Let’s use this to look at a tactic that Hit Subscribe uses to win over and over again, even with brand new sites that would otherwise struggle mightily to rank. This tactic is to write “response posts.”

Imagine this situation, with you as a searcher. What you’re really interested in is to understand the fastest way to learn C++, should you decide you want to. Here’s a sequence of events:

- You type “learn C++” and see the results dominated by landing pages and ads for C++ courses.

- Annoyed, you type instead “learn C++ fast” and you see a similar set of ads and courses and such.

- Really annoyed now, you angrily slam out on your keyboard “what is the fastest way to learn C++,” resorting, like some kind of animal, to typing the entire question.

And then, you see it, like a beacon in the night. An article that mirrors your exact search back to you in the title: “What is the Fastest Way to Learn C++ in 2021?”

What are you going to click, do you think?

When the searcher and you are both very specific about the question and answer, you will make them happy. And the search engine will, in turn, learn that your site, even though it doesn’t have much of a history, makes searchers very happy.

And when it learns that, you start to earn prodigious traffic, without worry about “building links” or other assorted marginal tactics.

SEO Checklists, Reexamined

That’s all of the tactical information for this post. Next up in the series, I’ll talk about keyword statistics basics, like understanding how many people search for a keyword and how difficult you’d find it to rank. But I want to close out here with an appendix of sorts.

At Hit Subscribe, we have a proprietary (ish, I mean, we share it) tactical SEO checklist for content. But we look at it from the perspective of pleasing the searcher, rather than the search engine. With that in mind, I’d like to walk through some SEO “best practices” on posts that probably seem (and often are) cargo-cult, thinking about how it impacts the searcher.

Let’s take a look at some of those.

Set Your Title and Meta Description

Take a look at one of the top results for a search for "sprint velocity " (really: "what is sprint velocity").

In LinearB's entry answering the question "what is sprint velocity", I've circled two things that pertain to what's often called the "meta" of the post: the meta title and meta description. Without getting too far into the weeds, this involves using meta tags to suggest to the search engine what title and description to show in its results. (And it is a suggestion, since Google doesn't always listen).

Popular SEO wisdom tells you to make sure to specify each and to make sure they don't end up truncated with an ellipsis. And I agree. But not because Google cares -- searcherscare.

Which would you rather click?

An article with a title that lets you know it will answer your question, along with a succinct description of the contents? Or something that says "Sprint Velocity Is Stupid..." and then a description that's just random text from the middle of the post?

These two pieces of information are your way to assure searchers that you will actually answer their question.

Keyword in the Title

SEO rules around keywords are, understandably, the ones that give skeptics the most pause. “Use your keyword in the title/headings,” after all, sound suspiciously like keyword stuffing or some other scumbag SEO play. And I suppose they could be if you think you’re tricking the search engine.

But consider keyword in the title from the searcher’s perspective.

You’re asking a question, either in full or elided format. What’s a stronger indication that an article will answer your question than them parroting your question back to you?

Including the target keyword in the title isn’t some algorithmic rule. It’s your way of assuring the reader that yes, I will answer your question with my content.

Keyword in Headings

Believe it or not, the same reasoning applies to including a keyword in at least one heading.

To understand that, imagine that the still-skeptical reader has clicked on your article to help answer their question. Your compelling meta title and description got them to click, but that’s it. They’re still not sold and still not committed to reading your entire article.

Instead, they scan the intro or scroll through, looking at… you guessed it… the headings in the article.

And what do you think their take is if they’ve googled “what is devops” and see no mention of “devops” in the introduction or any of the headings? They’re going to doubt your post will help, and they’re going to click “back” before actually reading.

And, by the way, it would be structurally weird for you to write an article whose purpose is to thoroughly define “DevOps” and not have a title of an H2 or H3 that even mentioned the concept.

It’s not about making google happy. It’s about assuring your reader you aren’t wasting their time with a bait-and-switch.

Readable/Scannable Content

If you’ve just started to use a tool like Yoast to optimize your posts, you might find yourself scratching your head at recommendations. They have all sorts of rules around max word count per heading, sentence length, images, page features, and more.

All of this really boils down to one thing: make the post scannable.

You don’t want walls of text. Instead, you want shortish sentences, short paragraphs, frequent headings, and lots of stuff breaking up text (quotes, lists, images, etc). If the post is long, an index with anchor text links can help.

This is all designed to lean into the fact that your searcher is planning to skim your post, anyway. Make that skimming a pleasant experience so that they’ll go back to the top and read in detail.

Page Load Speed/Performance

The last one I’ll mention is site performance. And this is the latter half of my world’s shortest guide to SEO:

Answer the questions that people ask and do it on a site that doesn’t suck to visit.

Put yourself in tactical search mode. Imagine that you’re furiously googling the text of some exasperating exception message a library is throwing. Really feel the annoyance and impatience of that moment.

Now, imagine that you click on a promising search result and… loading…. loading……………… still loading………..

What do you do? That’s right — you hit the back button and click on the next option without a second thought. You don’t have _time _for this nonsense.

If your site takes a long time to load or if the searcher experience landing on your site is generally janky, the rate at which people "pogo-stick" (immediately hit "back") goes through the roof. And that is terrible for your site's rankings.

In the end, it all comes back to the searcher experience. Understand their questions, answer those questions, help them, and do it in a way that isn't a miserable experience for them. That's it.

If your site takes a long time to load or if the searcher experience landing on your site is generally janky, the rate at which people “pogo-stick” (immediately hit “back”) goes through the roof. And that is _terrible _for your site’s rankings.

In the end, it all comes back to the searcher experience. Understand their questions, answer those questions, help them, and do it in a way that isn’t a miserable experience for them. That’s it.

Top comments (0)