By Jeanne Haskett, Nathalie Laroche, and Kimberley Brown

At the recent HugoConf, Jeanne Haskett, Nathalie Laroche, and Kimberley Brown — part of the Nuance Communications TechPubs team — presented their process for using Hugo modules, which enables efficient content reuse and consistency across Nuance’s multiple products. We found their presentation very helpful and informative, so without further ado, let’s find out more about…

How Nuance TechPubs stepped up their game with Hugo modules

The Nuance Technical Publications team recently moved to Hugo, which we love, and discovered that Hugo modules solve many of our consistency and standardization needs.

With a team of over 15 writers, and a portfolio that includes dozens of products, it’s important for our documentation to read, and look, like it’s coming from the same organization.

Enter modules.

The official Hugo documentation defines modules as follows:

Hugo Modules are the core building blocks in Hugo. A module can be your main project or a smaller module providing one or more of the 7 component types defined in Hugo: static, content, layouts, data, assets, i18n, and archetypes.

Our use of Hugo modules spanned three phases. We took it slow at first. But once we discovered how powerful modules can be, we went wild!

The journey

We’ve broken our journey into three phases to match three distinct goals:

- Phase 1: Consistency

- Pull common content into multiple Hugo projects, ensuring consistency. For example, archetypes and modifications to a theme.

- Phase 2: Branding

- Easily configure projects at the product level, to use different logos and favicons, and eventually entire CSS “skins”.

- Phase 3: Content reuse

- Share common content across all project repos but prevent modification: content fragments, entire topics, glossary definitions.

Phase 1: Consistency

In the first phase, we considered the contents of a typical Hugo project and identified the components that should be the same for all projects.

The common content that we centralized includes:

-

archetypesfolder, since we use it to provide writers with templates for new topics. For example, we write a lot of API documentation, so we created an archetype for gRPC topics that writers can use to quickly get started. Archetypes are a handy Hugo feature! -

assetsfolder, which contains some of our Docsy overrides like our logo. (We use the Docsy theme, which we love.) -

layoutsfolder, which includes theme overrides as well as our custom shortcodes. -

staticfolder, which includes common files like our favicon.

We took all these files and put them in a Hugo module, which we called, very originally, hugo-common-modules. 😉

If you’re familiar with Hugo modules, then you know that the next step is to configure your project to import the module. We decided to break the config.toml file into multiple configuration files for ease of maintenance.

Here is the content of our module configuration file, module.toml:

[[imports]]

path = "github.com/████████/hugo-common-modules"

disabled = false

[[imports.mounts]]

source = "static"

target = "static"

[[imports.mounts]]

source = "layouts"

target = "layouts"

[[imports.mounts]]

source = "assets"

target = "assets"

[[imports.mounts]]

source = "archetypes"

target = "archetypes"

...

Notice that we’re mounting the four folders that we need. Next, we copied this file into all our Hugo projects. This was pretty simple, as you can see, and fit our needs precisely.

Phase 2: Project-specific branding

At the beginning of our Hugo journey, we had plans to use the Hugo framework for one product, which meant a single look and feel. Pretty soon other writers on the team, writing for other products, wanted to use Hugo. This meant serving multiple products, each with slightly different branding. Our solution: Hugo modules!

We started by identifying the elements that would form part of the boilerplate or global template and put all that code in the respective files of the assets/ directory of our hugo-common-modules. To easily build and deploy our docs sets with different skins, we created a new directory called project-specific/. This directory, which contains subdirectories per product, houses each product’s proprietary logo and favicon, SCSS, and any file overrides specific to that product.

We then updated our module.toml accordingly. In the image below, “mix” is a product with its own logo, favicon, color palette, landing page images, and so on. By simply changing “mix” to another product name we can quickly switch to (import) an entirely different skin for an entirely different product.

Phase 3: Content reuse

Previously, we mentioned archetypes and how useful they are to the content development process. Archetypes allow us to standardize specific types of content like API documentation, for example, or a quick start or getting started topic. As mentioned, we were already using our hugo-common-modules to import archetypes.

Content reuse is not limited to entire topics. It can also include fragments of content, which some writers call snippets, that remain the same within a project or even across projects and are meant to be used again and again. Another example are common terms like glossary definitions. As you might expect, we expanded our use of hugo-common-modules to include content like snippets and glossary definitions. This approach satisfied our goal to write it once and use it in many different places.

However, when a project imports a Hugo module, the content is imported silently; that is, it does not appear in the project. This approach worked fine for files writers didn’t care about such as Docsy overrides, custom shortcodes, project-specific SCSS, and so on. To reuse content, however, writers needed to view it to determine if it suited their needs. Writers needed not only access to common content—shared in a single, central location—but also needed to see it.

Our solution: Vendor modules.

Hugo “vendoring” of content

Using a module that is “vendored” creates a _vendor directory in the project, which in our case allows writers to see the contents of the module dependencies as they’re working locally in the project. They can easily view the content of the files and reference the local filepath of shared content they wish to reuse, since “vendored” content behaves as if it belongs to the project.

Note: If you use this approach in Git, remember to add the _vendor directory to your .gitignore file to avoid committing it, since you only need it when working locally in the project.

This approach also nicely fulfilled our goal of ensuring consistency: Should a writer feel inclined to change a shared content file—and they often do!—he or she can do so only by submitting a merge request via the hugo-common-modules project, since local changes to “vendored” content are not retained once you do another import (run hugo mod vendor again).

Nice. That solution worked for us! But that’s not the end of our journey.

Sharing doc sets

What about documentation sets that form part of other doc sets? Consider a component that is common to many different products such as a license server. It might even “stand alone” as a product.

For a small product we might decide to place the documentation for installing and configuring the license server at the top level of the doc set; however, for a complex product we might prefer to pull the content into a “Requirements” section that includes additional prerequisites.

Once again, Hugo modules to the rescue: We simply store the license server documentation in its own module, which we then pull into each project at the desired location via the project’s module.toml file.

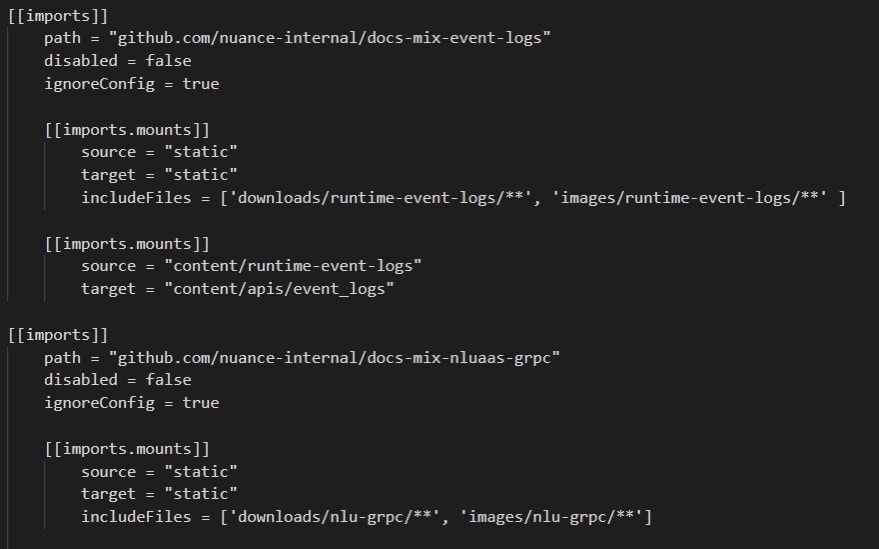

In this example, we are importing documentation and images from two modules (docs-mix-event-logs and docs-mix-nluaas-grpc) and specifying the path of both the source and target files.

Recap

In summary, modules have created a ton of value for us. We have been able to successfully apply archetypes and theme overrides, project-specific branding, and content reuse, all with the help of modules. And we’re only getting started.

What’s next

Since we presented at HugoConf, we’ve added Docsy as a module, greatly simplifying the workflow for writers.

Next, we plan to create a series of dashboards that will read in the content of all the component modules we use. These dashboards will allow us to see at a glance all the shared content, across all projects. Think of it as the control room for all things documentation.

Who we are

We’re the “terrible trio” (😉), also known as the “Hugo Admins”, in our TechPubs group. Feel free to watch our HugoConf tech talk on this subject and to contact us with any questions, comments, or suggestions. Also be sure to check out Kim’s lightning talk on Implementing conditional processing in Hugo, another innovation we can’t live without.

Jeanne Haskett

Content Architect & Senior Principal Technical Writer

Nuance Communications

jeanne.haskett@nuance.com

Nathalie Laroche

Senior Principal Technical Writer

Nuance Communications

nathalie.laroche@nuance.com

Kimberley Brown

Frontend Developer

Nuance Communications

kimberley.brown@nuance.com

Top comments (0)