This article was originally published here

Prologue

If you’re like me, you may be a little jaded towards the Golden Ratio and the Fibonacci numbers. If you aren’t already, I invite you to search YouTube for videos related to either topic — I had a look and I was suggested a video entitled “The Golden Ratio - Transmuted Pain to Power in Infinite Divine Proportion”. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of garbage out there.

The Golden Ratio was familiar to the Greeks, and much of its allure comes from Greek philosopher’s obsession with the number. An allure that is evermore powerful today, as all three Abrahamic religions were greatly influenced by Greek philosophy, especially by the Neoplatonists. Unfortunately, while I’m sure it is possible to have an enlightening discussion about the role of the Golden Ratio in Greek philosophy and religion, much of the content concerning Phi makes a mockery of both philosophy and theology. To say nothing of mathematics.

That means that this article is not for you if you’re here because you expected me to tell you how to cure cancer by using 1.618 cups of flour instead of 1.5. Instead, I’d like to take a poke at why the Golden Ratio and the Fibonacci Numbers are related in the first place, while also making a short review piece for those studying linear algebra.

The Math

You may be familiar with the Binet formula for the Fibonacci numbers:

If not, you should watch this video, it's really quite a nice exploration of the formula.

But where does this formula come from? Well, it comes from observing that we can recontextualize the familiar Fibonacci series in matrix form:

This version is quite simple, but it's also quite uninteresting. However, if one adds another row to our matrix we will have a square matrix A, which unlocks a great many tools of linear algebra. Our second row will simply compute the previous Fibonacci number:

This is nice and all, but we want a more efficient way to compute this, not just a more mathy way. Fortunately, we can have both; we'll start by finding the eigenvalues of this matrix, which are the roots of the characteristic polynomial:

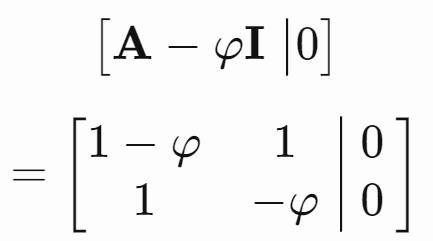

This has roots of 1 ± √5, which we typically write as φ and -(φ)^-1. The corresponding eigenvectors are non-zero solutions to (A− λI)x = 0 for an eigenvalue λ.

We find the eigenvector associated with λ = φ by row-reduction on the following matrix:

Which is row-equivalent to:

This matrix encodes a system with the following solution set:

Therefore an eigenvector associated with λ = φ is ⟨φ,1⟩. Similarly, an eigenvector associated with the other eigenvalue is ⟨−φ^−1,1⟩.

These choices are not unique, we could've chosen any of the infinite parallel vectors (except for the zero vector).

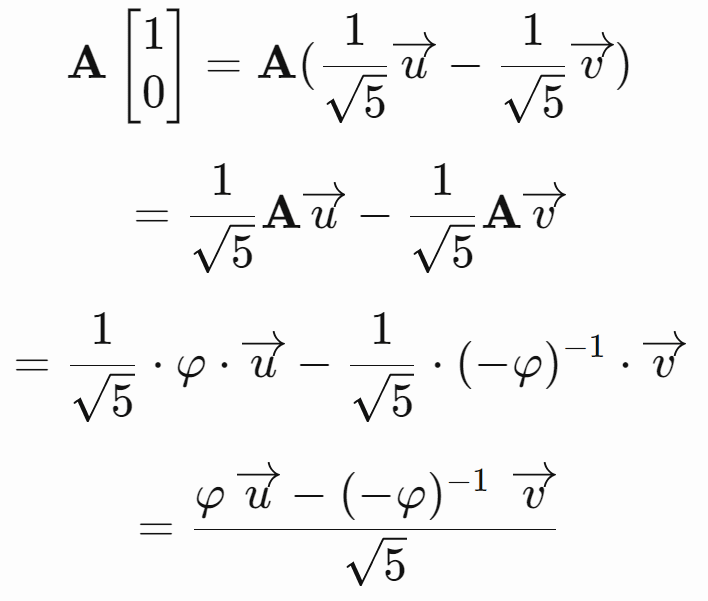

As we have two eigenvectors from different eigenspaces (i.e. are associated with different eigenvalues) we know they are linearly independent, and thus form a basis of ℝ^2. The vector ⟨1,0⟩ is thus necessarily a linear combination of this eigenbasis:

Therefore, if we multiply by A we only need to multiply each coefficient by the respective eigenvalue:

And if we multiply by A^n:

This lets us create a closed-form expression by solving for F_n which if you recall is the second element in our vector:

And so there we have it, we've derived Binet's formula.

Top comments (0)