Design artifacts created by human beings are everywhere. They surround us all the time if we want this or not. And I’m not only about visual stuff like logos, signboards, shields, and not only about different kinds of UI (graphical, voice etc). Service design is something we interact with many times throughout the day.

All the different scenarios we use to register on the website, fill the tank on gas station, order a pizza, online and offline, are architected by someone (intentionally or not). Obviously: smooth flow of all the small actions included in this service is good for all the parties, and broken flow (or difficult to follow one) is not. How to create the proper service? I strongly believe: 90% of success is just following the common sense + your ability to put yourself in someone’s shoes, empathise. The rest 10% is the knowledge about methodologies, best practices and helping tools you could get at variety of service / product design educational programs. I’m a UI engineer, working daily with JavaScript, front-end frameworks, progressive web apps features, and I consider architecting UX (User eXperience) as a inseparable and natural part of my job.

Let’s talk today about one simple(?) service: organizing public wi-fi in the airports. Not about the one in general (for sure, we expect it to be fast, reliable, secure), but about onboarding step. I’m a frequent traveller with 58 international flights I already had in 2017 and 25+ planned for the rest of the year. As you can imagine, I meet this connecting to wi-fi process in different airports quite often. Well, after cancelling the international roaming in Europe it’s not so critical anymore for the most of my travels, but “no need for wi-fi at all” it’s still a best case scenario (when you have European SIM-card, you travel inside Europe, and you don’t care so much about the volume of consumed cellular traffic). Actually, majority of the points we discuss in this article are applicable to the most of public wi-fi networks. The specifics of airport ones is:

- Large scale and diversity. Service should work fine (hereafter by “work fine” I mean not technical aspects, but the smoothness of onboarding procedure) for the large number (thousands) of people with totally different technical skills, speaking different languages, using different devices.

- Security limitations. I’ve never met 100% open networks in airports. You have to provide some data, at least your agreement, sometimes quite implicit, of terms & conditions (oh, these two brothers require a separate article). The set really depends on the country, and, I want to believe!, all the information they gather is required by the legal regulations, not by the marketing department.

- Fast and non-obtrusive onboarding due to venue specificity. But stop. By this point we started to list what we actually want from this process. It deserves a separate chapter.

What was the occasion for me to write this spontaneous article? Very simple: another awful wi-fi onboarding experience I’ve met. I completely failed to connect to the network of the airport I’m chilling in at the moment (wait a bit, I’ll give you all the details of this horror), so I started my offline text editor and typing. Why do I do it? To make a world a bit better! If this text convinces at least one service designer / wi-fi network maintainer / big boss of large public venue to go for some improvements in onboarding process — I’m the winner!

Let us set the mission. By “us” I mean the folks responsible for the design of the service, i.e. having some influence (or at least the possibility to strongly advice) on some parts of the flow:

To provide the wi-fi for everyone who ever need it at our airport, and to keep our customers happy by it.

Both parts are important for business. Providing a service/product causing good emotions is a foundation of UX, and deserves a separate article. Based on the goal we could assume:

- We lose money on each unsuccessful try to get the service. And this is actually so.

- We potentially lose a customer (and then lose money, following a point above) on each case, where the customer was unhappy during getting the service (“Next time I’ll just read an offline newspaper instead of going through this painful onboarding process again”).

So let’s save the money for our company (via saving the money for our service design customer) and go completing our mission!

What is our dream onboarding process

- Public wi-fi should be free. Period. With a bandwidth enough for regular entertaining/business activities: surfing, reading, emailing, using web apps, watching videos (I’m not talking about downloading full-size movies here). Probably, some business travellers will need something beyond this (with guaranteed high download/upload speed), but let’s focus on free service as on the подавляющее number of usecases.

- Back to onboarding. It should be as transparent as possible. The unreachable (because of security limitations) ideal is just an open network without any required actions, like your home wi-fi network, but without the password. You landed at the airport you’ve been before, bum —immediately get all your notifications from the last couple of hours. We should aspire to this. Important notice : I do not cover the possible security flaws like fake wi-fi networks. man-in-the middle attacks etc, I assume that we keep a full control on what’s happening with electromagnetic fields in our airport.

- If not 100% hidden, then onboarding should be fast and non-obtrusive. These two attributes are tightly coupled. Why fast? Because being on the run between the terminals is a widespread usecase, and nobody go for the onboarding process taking 10 minutes if they have only 20 minutes at all (bum! we lost a customer). Why unobtrusive? Same reasons. We do not relax for hours in the airports in a regular life, we are there for some mission: catch another flight, find a train to the city, i.e. we put our focus on the signs, screens, info shields, voice announcements, but not on the dialogs in our phone required to connect to the wireless network. In other words, we don’t want to be disrupted so much.

- Connecting to the wi-fi should be possible starting from the airplane parked to the gate. As a rule, we have a free minute while sitting and waiting for offboarding start. Why to spend precious time on looking at the window and thinking “why everything is so slow, I have my transit flight in 30 minutes, and I need the Internet to check the gate number!”

- No network coverage blind spots are allowed. This is really awful experience when you lost the connection in the middle of filling some form (oh, forms… we’ll take them below) and don’t event know that pressing “Go online” button will just reset everything.

Okay. Now we know how the proper public wi-fi onboarding should look like. Let’s go step by step taking smaller parts of the process and trying to come up with some dos and don’ts. Everything listed below is my personal opinion based on my personal experiences. I’ll be happy to get the feedback about your vision in the comments to this article. You are welcome to both support my points and argue with them. And it all starts with…

Naming

It all starts with the name, right? Good public wi-fi network name provides some advantages for free:

- Saving on spending resources (like ads), because there is no need to explain which network to choose for connection.

- Self-advertising. Some customers without a knowledge/thoughts about free wi-fi as available at the venue, could connect just because they see the network with proper name in the list

- Plays good for the brand credibility

Best practices

- Give a minimal required context for the user to help them to distinct your airport’s free network from the other ones. It’s also important later, outside the venue — when customer is managing saved wi-fi connections. What could be the minimal context? City name and/or airport name (it depends on how people reason about the venue), word airport itself. This is more than enough. Of course, there is no universal recipe, just follow the common sense, and go for how people are used to name your place. For example, there is no reason to use airport’s operator legal entity name if nobody except lawyers associates this with the airport.

Bad practices

- Use wi-fi as a part of the name. It’s just a waste of precious space. No doubts, customer doesn’t expect any other protocols in their wi-fi connection settings dialog.

- Use free as a part of the name. This is a discussion point. You could say “we have a paid network in addition, we have to show that this one is free”. My answer is: the product for the majority of your visitors is the free network. The name should be optimized (simplified) exactly for this audience. You can add an extra word like fast or so to your paid one. Rule of thumb: the network without a lock on the right and without a kind of “commercial” hint in its name is FREE.

Please, never

- Add telecom provider name, like SuperTelecom Airport Wi-Fi. Who cares, what’s used under the hood of your wi-fi ?Believe me, even the sweetest contract conditions you’ve got as a part of the deal requiring you to have this name, don’t worth the resulting mess. The worst case I’ve seen somewhere — is just a service provider name. What do you think — is it possible to engage visitors without explanation in this case?

- Use non-letter characters like _, *, !!! etc to “fix” the network names sorting and attract attention. Black marketing will not work in this case. The name looks fraudulent, suspicious, and not serious after all.

Number of the networks

The last “please never do” of the previous chapter was dedicated to the usage of naming hacks to distinct your free wi-fi network from dozens of others available at the venue. It’s sad, when your airport name starts with “Z”, and non-visible on the wi-fi connection dialogs without scrolling because of that fact, so why not to add “_” in the beginning?

Let me ask you another question. Do thousands of your visitors need these dozens of locked, technical, private networks like “Stuff Only”, “HP Cloud Print”, “BNNPKW” etc? We case so much about clean floors, following brand identity guidelines to keep visual part of the venue in order, we don’t like the noise in audio messages. This kind of the issue is the same! If there are 5 instead of 25 wi-fi networks available for connection, there is no need for these naming tricks. For sure, we are not going to ban our b2b partners’ (restaurants, shops) utility wi-fi networks as well as forbid airport’s technical ones. But there is a great option in wi-fi setup: to make these networks hidden. It shouldn’t be an issue: the employee who needs to get connected, will be told the network name.

For sure, there is no need to request to hide other public free wi-fi networks, exposed, for example, by cafes and restaurants located in airport. I’m only talking about applying some strict policies regarding utility, technical ones. Let’s keep wi-fi connection dialog lean!

Another strange case I met in one airport: 3 official free public wi-fi networks operated by different (probably, competing) telecom providers. And it was a mess. Of course, all the naming tricks like _ and even __ were on place.

Summary:

Best practices

- Have a very limited number of public free wi-fi networks visible.

Please, never

- Lose control on what’s happening with the number of wi-fi networks on the venue.

Flow and timing

I can recall the following main flows to get connected to the wi-fi in the airports (after you choose the proper network in your connection dialog and before you actually get the Internet access):

- Click the button/link.

- Fill some kind of the form with your personal details. From one-field form requiring email, to full-scale application-like ones.

- Choose a “sponsor”, watch an ad (video or banner). Or the same without the choosing stage.

- Enter your phone number in a form, wait for SMS with password, enter it in the next form.

- A variation of the form: create an account and log in. Or just log in (if you created this account earlier.

- One more method (see “What was the case inspired me to write this article?” chapter).

As a regular practice, the connection time is limited. From 30 minutes by the greediest airports to practically endless 24 hours. What’s happening after this time is up — depends on the case. Sometimes you just have to go for onboarding flow again, and get a new trial. Honestly, I don’t understand why there is a time limit. Our goal, as a service provider, to provide airport visitors with a connection to the Internet. What’s wrong with the passengers waiting for the flight longer than, say, 2 hours? I believe, during technical architecting stage, airport operator made all the assumptions about the number of simultaneous connections based on the number of visitors.

There is another case of wi-fi connection on/off requiring our attention: recovering from idle. I understand, keeping all the connections always alive significantly affects our possibilities regarding the number of connected devices. It’s not an issue to disconnect a device after some period of inactivity, but it’s really important to make sure, that restoring the connection will not force our customer to go through the onboarding process from the very beginning.

Best practices

- Keep the number of steps as close to 1 as possible. As you remember, we agreed that zero steps in an unreachable ideal.

- Reconnect after idle time without any actions needed from the customer.

Bad practices

- Sending SMS with a code to connect, if it’s not required by the law. It’s a very fragile method, you have to support all the variety of mobile providers, there are different conditions on receiving SMS, it will cost you the money, after all. Furthermore, you lose all the customers without the mobile phones, as well as with discharged ones, and all the international travellers not subscribed to the roaming.

Please, never

- Have the code/password in SMS longer than 4 digits (and containing something except the digits). I remember the case with 8-ish chars long password. You open SMS, copy it to the clipboard, return to wi-fi post-connection dialog, which already disappeared (after you switched to another app). It works fine to train the memory though :)

- Force people to watch an video ad. Even a minute-long video is a very disappointing in our specific situation. Your advertiser will not be happy by the loyalty to their brand metrics.

- Have the maximum connection time less than 2 hours. It’s just a shame.

Collecting data

I bet, 99% of data collecting cases in airports via the forms before connecting you to the Internet could be avoided. I absolutely understand — it’s great to know more about your venue visitors to make the service better. But there are many other channels working better than a form on your mobile device at the moment when you taking part in cross-terminal marathon and counting the seconds before next flight.

What’s about this 1%? Let’s keep it for the cases when some data required by the legal regulations in a certain country.

The rule of thumb: have a mortal combat with each single field of the data you was told to collect. Your goal: no form at all. All these metrics like age, gender, business/leisure trip etc — if marketing department really need it — have to be collected outside of wi-fi connection flow.

The separate evil is a request to create an account. Are you serious? I have to fill the form and expose my common password (or remember a newly created one) to join wi-fi network? My main question is WHY does airport need it? What value does it bring? I have a disappointing assumption — it’s “just to be”, or “it’s the standard flow of our Internet-provider”, or another unintentional, “unconscious” reason. And this situation has to be fixed.

There is another thought about collecting data in this very specific situation: you can never trust it. Just because people fill these forms on the go, they put any random information to just bypass the validators (okay, I’m talking about myself now and have the courage to extrapolate). Anyway, I’d not take the gathered statistics seriously. Why to gather it at all then?

Let’s conclude:

Best practices

- No form at all

- Require to accept Terms & Conditions implicitly, without a corresponding checkbox

- One, big, clear button to connect

Bad practices

- Collect data you don’t critically need

- Require to create an account

Please, never

- Have forms longer than 3 fields

The separate checklist will show the best practices for the forms (if you can’t avoid these)

- Do not forget to go for adaptive design. Large, visible fields and field captions, no horizontal scroll, hide everything non-important.

- Use type attribute of the html input. It will tailor the keyboard layout on mobile device helping user to enter, for example email.

- Avoid long select lists when possible. Choosing your country from 100+ items scrollable list is not a pleasure.

- Be explicit and helpful. If you need to collect a phone, try to make the corresponding field self-explaining, for example, having “+” on the left will give a hint about the format.

- For the checkbox make sure that its label is clickable as well.

- Provide clear error messages and give a hint on the way to fix in non-obvious cases.

- Check edge cases. Remember, we architect a service for the citizens of almost 200 countries of the world, with the tremendous diversity in their names, addresses/phones formats, and mindsets.

- Test, test, test (on the different mobile devices). Try to fill the form on the go. Check the number of seconds you need. Jump into the airport visitor’s shoes!

What was the case inspired me to write this article?

You can’t imagine. I will neither call the airport name, nor hide anything from the screenshots. If you wish, you can easily find it. Nowt follow the steps with me:

- You connect to the network with quite fraudulent-like name Free_Internet

- There you are faced with a fact: YOU NEED AN APP to get 30 minutes of the free wi-fi. And two options: I have the app, I don’t have the app.

- Okay. I click “I don’t” and get a form to enter my phone number crafted in the worst traditions: not clear which format to use, no way to enter “+”.

- Surprisingly, it accepts my phone number in international format without leading “+” and I get SMS with PIN required to enter.

- After submitting the next form with PIN I get generous 5(!) minutes of the Internet-connection to run to App Store or Google Play (hello non iOS/Android phones and laptops owners!) and download the app. I never took part in this kind of competition!

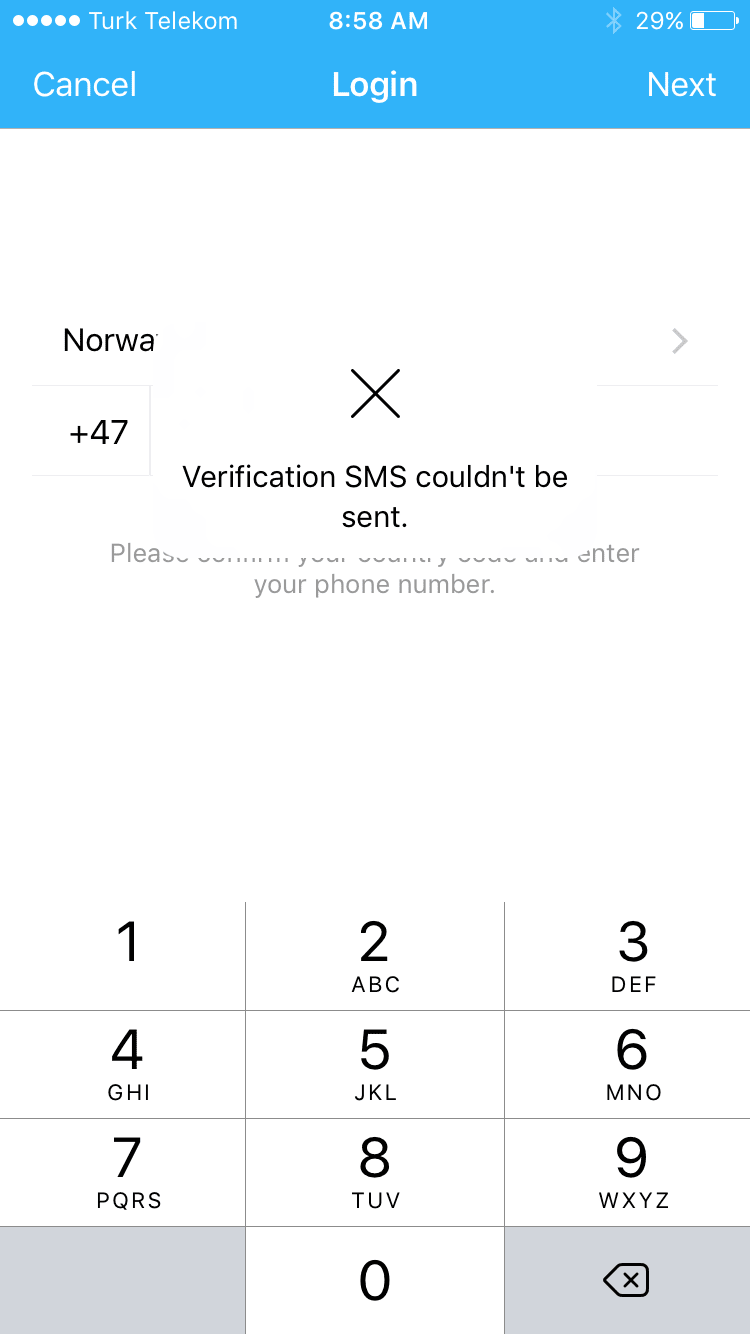

- Well, here is the app installed, “Wi-Fi” button found, now it’s time to enter your phone number again! An explicit bulky select of countries instead of entering two or three digits country code there — we still can live with it, just give us the Internet! Hit “Send” and this all-explaining error:

- I do not give up! Maybe I have to go to wi-fi properties and pick “Now I have this app” first? Go there. Click the button. Same form again-why do they need my name and number again? I have the app! Anyway, enter my info and get:

- This is the grand finale of your tries to get some connection to the Internet for today, Maxim. Please fly back to us in 24 hours and try your luck again. But be quicker!

I don’t have any idea what’s happened. Am I too slow in getting the app? But I have it now! Is there a need to go back to wi-fi connection dialog right after installing the app without trying to connect via the app? No idea. Is my phone operator not supported? But I get this SMS with the code for 5 minutes trial.

What do you think, which percent of potential wi-fi users go through this quest successfully? Even in the best case scenario, when everything works as intended, the number of steps is so hight and requirements are so obtrusive, that I suppose business owners are surprised by the low number of users. Just rearchitect the service to make it friendly to your customers and stop losing your money — quite obvious advice here.

What could be the opposite case?

To finish the article on the positive note, let me introduce the public wi-fi service in Oslo Airport.

- It meets you at/follows you to your seat in the plane

- You are one click away from the Internet. Just press a big-red-button (okay, purple one) and you are there! Terms & Conditions problem solved in a very user-friendly way.

- The only minor appeal I have — network name could be better. I don’t like when any title SHOUTS ON ME. Also giving a context about Oslo makes sense.

- Okay, there is a second appeal: we need fewer wi-fi network to be displayed. We could require to hide at least all locked ones. Our airport – our rules, and the customer is the king, right?

- To be mentioned: this close-to-perfection onboarding flow was not from the very beginning in Oslo Airport. I remember the times when you had to enter your phone number to get the password by SMS, then it was changed to the form requiring email (and got dozens of sdfhsdj@fjsdfjs.no from me and thousands of other users), and finally, after figuring out the really required things, it’s in a current form. Great job, Avinor (the operator)! My pleasure to visit my home airport.

Call for action

What are your experiences (bad and good) with airports’ wi-fi networks? Could you share some cases in the comments?

P.S.

For those who read by this line, I’ll share some personal frequent flyer tips:

- If you book a seat in a row of 3 with the following combinations: Free Free Free, Taken Free Free, Free Free Taken, go for the non-middle seat of options 2 or 3. There is a big chance to have a seat in the middle not taken after all (where you could put some of your stuff like jacket then)

- I personally prefer to book the front rows because it’s a better chance to go for visa/passport formalities first. Unfortunately it doesn’t work in case of transfer to the gate by bus. And yes, I know, back rows are safer according the statistics.

- If there is no free space in overhead compartment right over your seat, prefer the direction which you will use for offboarding. It’s easy to do some steps forward following people’s flow, rather than going in opposite direction to grab your backpack.

Top comments (0)