Software developers have a lot on their minds. There are are myriad of questions to ask when it comes to creating a website or application: What technologies will we use? How will the architecture be set up? What functions do we need? What will the UI look like? Especially in a software market where shipping new apps seems more like a race for reputation than a well-considered process, one of the most important questions often falls to the bottom of the “Urgent” column: how will our product be secured?

If you’re using a robust, open-source framework for building your product (and if one is applicable and available, why wouldn’t you?) then some basic security concerns, like CSRF tokens and password encryption, may already be handled for you. Still, fast-moving developers would be well served to brush up on their knowledge of common threats and pitfalls, if only to avoid some embarrassing rookie mistakes. Usually, the weakest point in the security of your software is you.

I’ve recently become more interested in information security in general, and practicing ethical hacking in particular. An ethical hacker, sometimes called “white hat” hacker, and sometimes just “hacker,” is someone who searches for possible security vulnerabilities and responsibly (privately) reports them to project owners. By contrast, a malicious or “black hat” hacker, also called a “cracker,” is someone who exploits these vulnerabilities for amusement or personal gain. Both white hat and black hat hackers might use the same tools and resources, and generally try to get into places they aren’t supposed to be; however, white hats do this with permission, and with the intention of fortifying defences instead of destroying them. Black hats are the bad guys.

When it comes to learning how to find security vulnerabilities, it should come as no surprise that I’ve been devouring whatever information I can get my hands on; this post is a distillation of some key areas that are specifically helpful to developers when handling user input. These lessons have been collectively gleaned from these excellent resources:

- The Open Web Application Security Project guides

- The Hacker101 playlist from HackerOne’s YouTube channel

- Web Hacking 101 by Peter Yaworski

- Brute Logic’s blog

- The Computerphile YouTube channel

- Videos featuring Jason Haddix (@jhaddix) and Tom Hudson (@tomnomnom) (two accomplished ethical hackers with different, but both effective, methodologies)

You may be familiar with the catchphrase, “sanitize your inputs!” However, as I hope this post demonstrates, developing an application with robust security isn’t quite so straightforward. I suggest an alternate phrase: pay attention to your inputs. Let’s elaborate by examining the most common attacks that take advantage of vulnerabilities in this area: SQL injection and cross site scripting.

SQL injection attacks

If you’re not yet familiar with SQL (Structured Query Language) injection attacks, or SQLi, here is a great explain-like-I’m-five video on SQLi. You may already know of this attack from xkcd’s Little Bobby Tables. Essentially, malicious actors may be able to send SQL commands that affect your application through some input on your site, like a search box that pulls results from your database. Sites coded in PHP can be especially susceptible to these, and a successful SQL attack can be devastating for software that relies on a database (as in, your Users table is now a pot of petunias).

You can test your own site to see if you’re susceptible to this kind of attack. (Please only test sites that you own, since running SQL injections where you don’t have permission to be doing so is, possibly, illegal in your locality; and definitely, universally, not very funny.) The following payloads can be used to test inputs:

-

' OR 1='1evaluates to a constant true, and when successful, returns all rows in the table. -

' AND 0='1evaluates to a constant false, and when successful, returns no rows.

This video demonstrates the above tests, and does a great job of showing how impactful an SQL injection attack can be.

Thankfully, there are ways to mitigate SQL injection attacks, and they all boil down to one basic concept: don’t trust user input.

SQL injection mitigation

In order to effectively mitigate SQL injections, developers must prevent users from being able to successfully submit raw SQL commands to any part of the site.

Some frameworks will do most of the heavy lifting for you. For example, Django implements the concept of Object-Relational Mapping, or ORM, with its use of QuerySets. We can think of these as wrapper functions that help your application query the database using pre-defined methods that avoid the use of raw SQL.

Being able to use a framework, however, is never a guarantee. When dealing directly with a database, there are other methods we can use to safely abstract our SQL queries from user input, though they vary in efficacy. These are, by order of most to least preferred, and with links to relevant examples:

- Prepared statements with variable binding (or parameterized queries),

- Stored procedures; and

- Whitelisting or escaping user input.

If you want to implement the above techniques, the linked cheatsheets are a great starting point for digging deeper. Suffice to say, the use of these techniques to obtain data instead of using raw SQL queries helps to minimize the chances that SQL will be processed by any part of your application that takes input from users, thus mitigating SQL injection attacks.

The battle, however, is only half won…

Cross Site Scripting (XSS) attacks

If you’re a malicious coder, JavaScript is pretty much your best friend. The right commands will do anything a legitimate user could do (and even some things they aren’t supposed to be able to) on a web page, sometimes without any interaction on the part of an actual user. Cross Site Scripting attacks, or XSS, occur when JavaScript code is injected into a web page and changes that page’s behavior. Its effects can range from prank nuisance occurrences to more severe authentication bypasses or credential stealing. This incident report from Apache in 2010 is a good example of how XSS can be chained in a larger attack to take over accounts and machines.

The annual DOM dance-off receives an unexpected guest);

XSS can occur on the server or on the client side, and generally comes in three flavors: DOM (Document Object Model) based, stored, and reflected XSS. The differences amount to where the attack payload is injected into the application.

DOM based XSS

DOM based XSS occurs when a JavaScript payload affects the structure, behavior, or content of the web page the user has loaded in their browser. These are most commonly executed through modified URLs, such as in phishing emails.

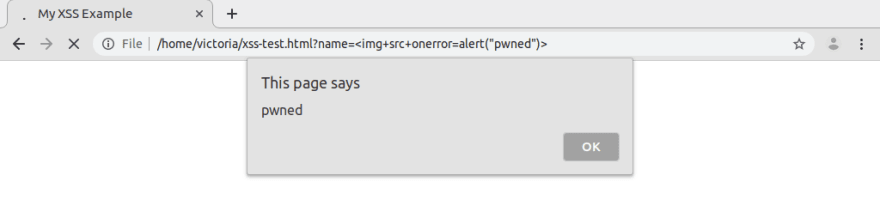

To see how easy it would be for injected JavaScript to manipulate a page, we can create a working example with an HTML web page. Try creating a file on your local system called xss-test.html (or whatever you like) with the following HTML and JavaScript code:

<html>

<head>

<title>My XSS Example</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1 id="greeting">Hello there!</h1>

<script>

var name = new URLSearchParams(document.location.search).get('name');

if (name !== 'null') {

document.getElementById('greeting').innerHTML = 'Hello ' + name + '!';

}

</script>

</h1>

</html>

This web page will display the title “Hello there!” unless it receives a URL parameter from a query string with a value for name. To see the script work, open the page in a browser with an appended URL parameter, like so:

file:///path/to/file/xss-test.html?name=Victoria

Fun, right? Our insecure (in the safety sense, not the emotional one) page takes the URL parameter value for name and displays it in the DOM. The page is expecting the value to be a nice friendly string, but what if we change it to something else? Since the page is owned by us and only exists on our local system, we can test it all we like. What happens if we change the name parameter to, say, <img+src+onerror=alert("pwned")>?

This is just one example, largely based on one from Brute’s post, that demonstrates how an XSS attack could be executed. Funny pop-up alerts may be amusing, but JavaScript can do a lot of harm, including helping malicious attackers steal passwords and personal information.

Stored and reflected XSS

Stored XSS occurs when the attack payload is stored on the server, such as in a database. The attack affects a victim whenever that stored data is retrieved and rendered in the browser. For example, instead of using a URL query string, an attacker might update their profile page on a social site to include a hidden script in, say, their “About Me” section. The script, improperly stored on the site’s server, would successfully execute at a later time when another user views the attacker’s profile.

One of the most famous examples of this is the Samy worm that all but took over MySpace in 2005. It propagated by sending HTTP requests that replicated it onto a victim’s profile page whenever an infected profile was viewed. Within just 20 hours, it had spread to over a million users.

Reflected XSS similarly occurs when the injected payload travels to the server, however, the malicious code does not end up stored in a database. It is instead immediately returned to the browser by the web application. An attack like this might be executed by luring the victim to click a malicious link that sends a request to the vulnerable website’s server. The server would then send a response to the attacker as well as the victim, which may result in the attacker being able to obtain passwords, or perpetrate actions that appear to originate from the victim.

XSS attack mitigation

In all of these cases, XSS attacks can be mitigated with two key strategies: validating form fields, and avoiding the direct injection of user input on the web page.

Validating form fields

Frameworks can again help us out when it comes to making sure that user-submitted forms are on the up-and-up. One example is Django’s built-in Field classes, which provide fields that validate to some commonly used types and also specify sane defaults. Django’s EmailField, for instance, uses a set of rules to determine if the input provided is a valid email. If the submitted string has characters in it that are not typically present in email addresses, or if it doesn’t imitate the common format of an email address, then Django won’t consider the field valid and the form will not be submitted.

If relying on a framework isn’t an option, we can implement our own input validation. This can be accomplished with a few different techniques, including type conversion, for example, ensuring that a number is of type int(); checking minimum and maximum range values for numbers and lengths for strings; using a pre-defined array of choices that avoids arbitrary input, for example, months of the year; and checking data against strict regular expressions.

Thankfully, we needn’t start from scratch. Open source resources are available to help, such as the OWASP Validation Regex Repository, which provides patterns to match against for some common forms of data. Many programming languages offer validation libraries specific to their syntax, and we can find plenty of these on GitHub. Additionally, the XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet has a couple suggestions for test payloads we can use to test our existing applications.

While it may seem tedious, properly implemented input validation can protect our application from being susceptible to XSS.

Avoiding direct injection

Elements of an application that directly return user input to the browser may not, on a casual inspection, be obvious. We can determine areas of our application that may be at risk by exploring a few questions:

- How does data flow through our application?

- What does a user expect to happen when they interact with this input?

- Where on our page does data appear? Does it become embedded in a string or an attribute?

Here are some sample payloads that we can play with in order to test inputs on our site (again, only our own site!) courtesy of Hacker101. The successful execution of any of these samples can indicate a possible XSS vulnerability due to direct injection.

"><h1>test</h1>'+alert(1)+'"onmouserover="alert(1)http://"onmouseover="alert(1)

As a general rule, if you are able to design around directly injecting input, do so. Alternatively, be sure to completely understand the effect of the methods you choose; for example, using innerText instead of innerHTML in JavaScript will ensure that content will be set as plain text instead of (potentially vulnerable) HTML.

Pay attention to your inputs

Software developers are at a marked disadvantage when it comes to competing with black hat, or malicious, hackers. For all the work we do to secure each and every input that could potentially compromise our application, an attacker need only find the one we missed. It’s like installing deadbolts on all the doors, but leaving a window open!

By learning to think along the same lines as an attacker, however, we can better prepare our software to stand up against bad actors. Exciting as it may be to ship features as quickly as possible, we’ll avoid racking up a lot of security debt if we take the time beforehand to think through our application’s flow, follow the data, and pay attention to our inputs.

Top comments (3)

Very good information @victoria ! We should always use frameworks if possible to help avoid most of these issues

I had to learn this the hard way at my first job. 😫

Fellow devs, hold this article dear and you'll be good for a long time to come. 😁

Very informative! Thank you.