I’ve been to plenty of bad interviews. Sometimes, only some questions are bad, but usually it goes further than that. Bizarre questions like “what’s the difference between a number and an array” are just a symptom of deeper issues.

Let’s take a step back — why are we interviewing? To hire someone — in our case, a software developer — good at building working software (or at least, ahem, with a good outlook), in our team. A good interview process is precise (not hire people who can’t build software, and not reject people who can), and fast (to save our team’s time, and hire the candidate before anyone else does). That’s it, really. Hire good candidates with a reasonable precision / time ratio.

If this sounds trivial, then why do some interviewers…

- Enjoy making the candidate look stupid?

- Ask questions that every sane person googles in real-life?

- Not help a struggling candidate as they would a struggling teammate?

- Ask random questions off the top of their head instead of planning ahead?

- Or, conversely, stick to a hard plan even as it stops making any sense?

- Spend time asking things that are on your CV?

- Have four interviews where one would suffice?

- Get into large groups, interrupting each other?

Because they’re bad at interviewing, that’s why. Or, being more positive — because they’ve lost sight of the goal to be achieved behind the ritual. In this article, I go over the major sources of my frustration with interviews, and share some advice for improving your interviews.

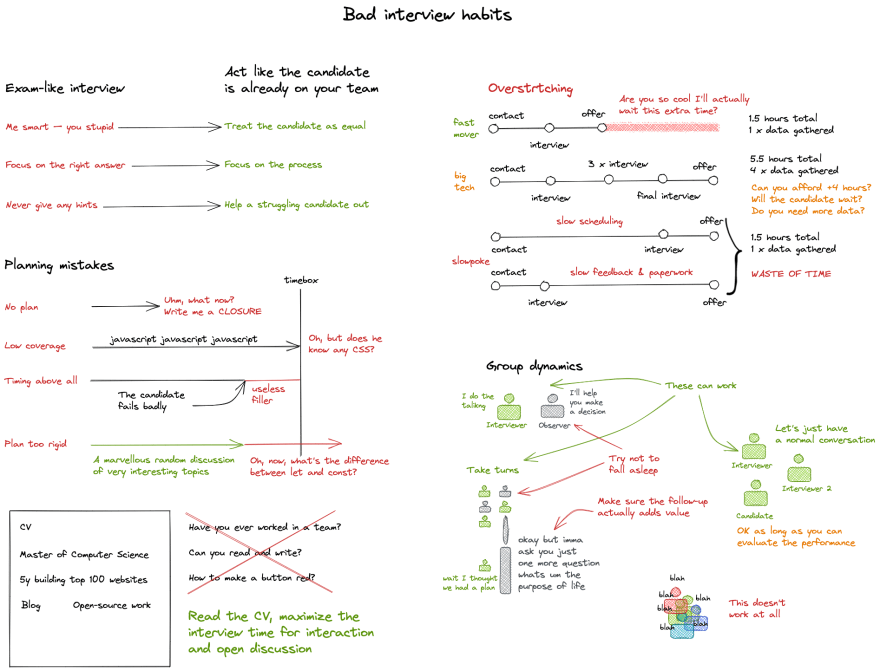

Me smart — you stupid

You can’t do much worse when interviewing than adopt “me smart — you stupid” mentality. Let’s face it, feeling smart is nice. The interviewer has all the answers, while the candidate doesn’t. It’s tempting to act like a genius from another planet who knows everything and be like “oh come on think again” and “even my grandmother can do it”. Bad.

This approach obviously misses the whole point of interviewing — we’re trying to hire someone, not humiliate as many people as possible. As such, it’s more evident in larger companies, where the interviewer is often not the person looking to strengthen his team, but some random fellow whose primary objective is to have lunch ASAP.

I also call these interviews exam-like. To pass, you need to give a correct answer to each question on a list. Not a good model for an exam either, but it’s what many of us grew up with. Anyways, an interview is certainly not an exam. The examiner is much more knowledgeable than the student, which is often not true for interviews (especially not middle / senior-level ones). Most exams cover specific known topics, while strict developer curricula don’t exist. Finally, while both exams and interviews can be a selection mechanism, exams have an extra goal of giving the student an objective overview of his abilities. You see, different things.

So, never assume you’re smarter or somehow better than the candidate. But this is just the first step away from exam-like interviews — two other, less evident treats are focusing on the answer and not giving any hints.

Focus on the answer

A common feature of exam-like interviews is the checklist approach. The interviewer asks the question, the candidate answers, we up the score if the answer fits, and move on. The questions therefore tend to be very closed, to facilitate checking correctness, and the difficulty level is tuned by choosing more esoteric topics: a junior JS developer tells about let vs const, the senior — about the event loop.

Real software development is rarely about quickly answering very specific questions. In fact, “how to check browser support for server-sent events” is the most minute detail usually fixed by googling at the final stage of problem-solving. What is it about, then? Many things:

- Brainstorming possible approaches

- Decomposing a task into bite-sized subtasks

- Iterating on the idea to find weak points

- Collaborating with teammates

And I haven’t even touched the actual coding yet. Not saying code interviews are worthless, but you get more bang for your buck and test several skills at once by focusing on the problem-solving rather than the right answer.

Problem-solving naturally favors more open-ended questions like “design a slider gallery”, over “what touch events exist”, because they have more process, and thus avoid most of the pitfalls I described in my earlier article on bad interview questions.

Caveat: answer-centric questions work well for screenings. A non-technical recruiter can ask a few sane questions like “What are some React hooks?” and I’m like “useRef useMemo useEffect”, and we know I’m legit. The lack of trust is slightly annoying, but I’ve seen many candidates who can’t tell an iterator from a cucumber, so I feel you.

Not giving any hints

The final treat of “exam-like” interviews that can persist in realistic coding tasks is leaving the candidate alone with the problem, not helping where it’s due. The thinking is that a senior-level developer must know this, and if I don’t — I’m obviously not one. Again, that’s not how development works.

Do you immediately fire or report your teammate who misses a corner case, has room for improvement, or is completely lost? Hopefully not. Collaboration is a key development skill, and you help your friend out, right? Why, then, should the interview be the other way around? Sure,it’s best to plan for edge cases in advance, still cool to identify them yourself and iterate, but it’s not too bad if you can admit and fix a mistake pinpointed to you.

Worst case — don’t even show you’re not satisfied with the answer at all. “So, this is your final answer? Let’s move on then” (to yourself: “Stupid stupid Vladimir, I’ll never hire you”). Happened to me — I solved a particular algorithm problem in linear memory three times in three separate interviews until one interviewer told me that an constant-memory solution actually exists. Until then, I believed the first two rejected me just because they disliked my attitude.

There’s no shame in helping a struggling candidate!

Poor planning

Many interviewers drop in from their daily job with a “fuck, I’m interviewing in 3 minutes!”, don’t have a question list ready because “I’m a senior engineer, I’ll know my senior buddy from a mile”, and proceed with some trivia from a random “best question list” found online (during the interview, of course) or the last tricky thing they’ve done in their job — both poor choices. I know this because I’ve done it myself, and I’m sorry. Planning is king.

Let’s handle the questions first. Ideally, you want to cover several topics related to the role. In a front-end interview these are probably JS/TS, CSS, and some React (or whatever you use) / algo / deployment / performance. Nice way to go through a topic: a few closed question -> open question -> full-on software design task. There are many interdependencies and constraints, so trying to come up with questions on the fly is guaranteed to fail unless you interview daily.

Timing is not as important as you think. Finishing early is fine — whether the candidate aces all the questions in 10 minutes, or fails even the most basic ones, once you got what you came for, filler talk is not the best use for leftover time. Running badly over-time is worse, because something might be scheduled right after the interview, but easily fixed by announcing the duration with a 30-minute extra, e.g. plan for 1.5 hours for a 1-hour interview.

While we’re at it, locking yourself into a very strict script is no better than having no plan at all. If the question sparks some interesting discussion, don’t kill it just to ask more low-level stuff. If you were looking for a senior developer, but happen to have a good junior before you, you’d better adapt — a good junior is still useful and hard to come by. If the candidate has never worked on performance optimization, there’s no use asking in-depth about TTI measurement. Open-ended tasks give you more flexibility in all these cases than “senior-only” questions.

So, do prepare the list of questions that reasonably cover the topics you care about, but don’t obsess over that plan too much — at the end of the day, you’re after a candidate to reinforce your team, not a walking encyclopedia of development.

Ignoring the CV

Interviews are precious face time with the candidate best used to get to know each other, judge social and problem-solving skills. Why waste this opportunity on reiterating things that are evident from the CV?

I worked on large-scale products in big tech companies, got a degree from a top university, and even have a blog and some open-source work — it’s all on my CV, and learning it takes 15 mins before the interview. Not bragging, but it shows I’m probably not too bad. Now, you have a right to be suspicious — maybe I’m a con artist who just made up my CV and forked some repos. A few low-level questions like “sum numbers in an array” are fine. But why spend an hour on “now, write a FUNCTION” and “have you ever worked in a team”? You haven’t taken a single look at the data you had on me, have you, lazy bastard?

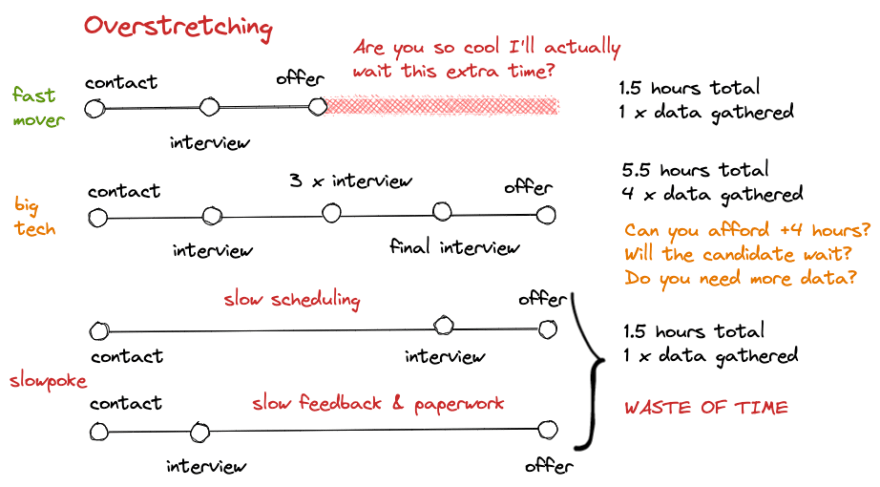

Overstretching

Big tech companies are famous for lengthy interview processes: Google has about 8 interviews, and other tech giants are not far behind. So, as a 3-person startup that wants to be the next Google, you need to have many interviews, right? Not so fast. Large companies have many factors that let them get away with (and even require) lengthy interview processes:

- The candidates are motivated to work in this particular company and are less likely to accept faster offers while interviewing with you.

- A steady stream of candidates justifies high rejection rates and requires ranking precision only achieved by collecting more data.

- Many employees available for interviewing. It’s fine to spend 80 hours on 10 candidates when it’s 0.02% of your team’s time, not so much when it’s 67%.

- Many teams are hiring at any time, and they reasonably want to have some personal time with the candidates.

I’m fine with 2 interviews and a phone screening, as long as I genuinely like your place, and you can schedule them within a week or two. I’m a lot less enthusiastic about spending 4 hours with a very talkative team lead in your average outsource agency when I can get a comparable offer in a day. Requiring a larger time commitment shows how amazing you think you are. You’d better really excite the candidate more than the companies with shorter hiring processes do.

Having too many interviews is not the only way to overstretch the process. You can only have two, scheduled too far from each other, or be generally slow to organize them and gather feedback. I’m no expert on office administration, but remember that your goal is to hire people before they accept another offer, so please do your best here.

So, only add more interviews if you really need them, and your offering justifies the extra time required. Also remember that extra interviews are not free for your team.

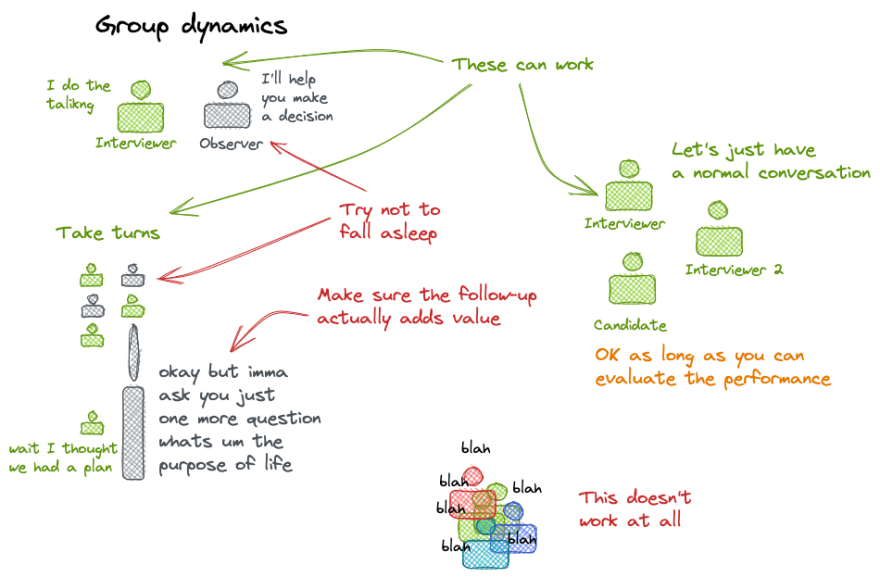

Poor group dynamics

Luckily, 1-on-1 interviews are the standard. However, there are good reasons to have more interviewers: you get a second opinion (as we say in Russia, “one head is good, but two are better”), and several teams that are hiring get to see the candidate in action. However, I often see problems with group dynamics.

Several interviewers, competing and interrupting each other, is just a mess. This might work if you’re making a normal (as possible under the circumstances) conversation without the whole question-answer thing, but these informal interviews have their drawbacks — prioritizing social skills and making it hard to compare many candidates. In a traditional QnA format, it’s better to have one interviewer in charge at any time, with others observing. You can switch roles by section or by answer if you like. But still, there are dangerous spots.

One pitfall is follow-up questions. Every interviewer wants to ask one, then it gets out of control and the follow-ups add no value beyond showing the second interviewer’s here. Once I’ve interviewed with 8 (yes, eight) people at once, and once they were done with their follow-ups to the first question, the time was up and nobody seemed really happy. You often get some back-end dude hiding in the dark to assault you with “OK you can paint your buttons, but can you make me a fault-tolerant DB persistence layer” — wut? Make sure every follow-up helps you assess the candidate better, and isn’t just something that sprung to your mind (see section on not planning ahead).

Another problem that arises with a “passive” interviewer is boredom. Listening to the same answers for the tenth time is not always exciting. However, it’s not very reassuring to see a visibly bored interviewer, especially one who starts playing with the phone because business. The worst of I’ve seen a bored interviewer do is reach into his pants, take something out and chew on it. Hope it was a candy. I needed time to accept this experience.

If you bring buddies to the interview, make sure to agree on who asks what in advance, avoid useless follow-ups that assert your smartness, and make sure not to fall asleep when it’s not your talking time.

Many things can make interviews a horrible experience. Here are some tips to be a better interviewer:

- Focus on finding out what the candidate is good at, not on showing off how smart you are. Yes, even if you’re not hiring for yourself.

- Seeing how the candidate approaches problems, is better than getting some particular answer you expect. Open questions suit this style better.

- If the candidate struggles, help out! People will get stuck in real life, and acting on feedback is a useful skill.

- Prepare a question plan that reasonably covers the topics you care about — it’s hard to come up with questions as you go.

- But also make sure the plan is flexible enough to allow for unexpected turns. Is hiring a senior engineer experienced in performance optimization really the only good outcome? Don’t you think people are capable of, uhm, learning?

- Get as much data on the candidate as possible beforehand — CV, open source work, shared acquaintances and previous interview results are your friends. Asking this again and again is a waste of precious face time.

- Don’t make the interview process longer than it needs to be with more interviews or poor scheduling. If you add an interview, you’d better be sure the candidate will want to invest the time in it.

- If you have several interviewers, agree on who asks what, make sure the follow-up questions add value beyond showing you’re here, and try not to fall asleep when not talking. Alternatively, try a “conversation-based” interview if it works for you.

Above all, keep you end goal in mind — to hire someone who’ll help you build your product. Happy interviewing!

Top comments (0)