"All models are wrong, some models are useful" - George Box

There is no universal standard on good or bad. Here are my AAA principles on defining good software architecture:

- Accountable: good software architecture makes each team hold accountability for its corresponding business objective

- Autonomous: good software architecture should allow each team to move on largely independently without being blocked by others too frequently

- Amortized: good software architecture promote forward thinking, allows the upfront cost of infrastructure amortized

Accountable >> Autonomous > Amortized. In the 90s, code reuse (Amortization) is hot in object-oriented community. Then SOA/DDD emphasize a lot on Autonomy. But I found both Amortization and Autonomy are ambiguous for guiding the boundary definition in practice. It is hard to convince people, X is better than Y. Really, the functionality of a module should derive from its responsibility.

Developers can not estimate

"Accountable" really is the key here. I see "the lack of accountability" is the biggest crisis of software development, it is bigger than "unable to manage so-called complexity".

It is not a secret that developers can not estimate. It brings a lot of very fundamental problems to good software engineering:

- Because we never know how many people are really needed, middle-management will just add as many people as head-count allows. Why? It is simple, they get paid according to how many people they are currently managing.

- There is no business value to refactor the software to keep it "maintainable". What does maintainable mean? Throw enough people to the problem, it can always be solved. Software engineering is not rocket science, how hard can it be?

To solve this problem is not about figuring the magic of story estimation, instead, we should not need to estimate if we are working with the business owner as the same team. Every software team will have one and only one corresponding business team, they share exactly the same OKR. It is important to be responsible for only ONE thing.

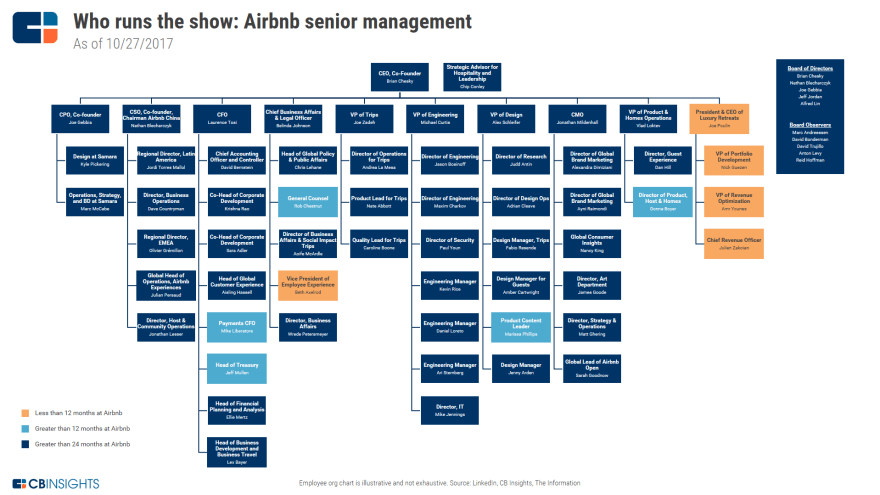

This is a typical organization chart of the business. Every smaller team will have their OKR aligned with their parent team. The key results of OKR will be measurable so that each team can be accountable for something.

Typical bad software architecture looks like this: There are a lot of small teams owning their micro-services. The business owner typically needs support from multiple micro-services to accomplish their goal. Every requirement will need to be communicated to different software team again and again. The software team can not name a clear business objective for their micro-service, and because of that, they can not tell what contribution are they making to the business.

Let me emphasize again: the NO.1 goal of software architecture is to make software team accountable for the business.

Bounded Context

In the large scale, architecture is about bounded contexts (read DDD for more details). This is just the business organization chart reflected in the software world:

Take the e-commerce domain as an example, the business is divided into several bounded contexts. There is no single team can cover the business process across the bounded contexts. This is generally a good thing here, the big problem is decomposed into smaller problems, and the team of business and technology can work together in one bounded context towards the common goal.

Cyberspace & Agents

One bounded context is still too large for one team. At least we believe that is the case in micro-service mindset. How to break it further down into more manageable pieces? My model is "cyberspace & agents". What we are building as programmer essentially boils down to two things:

- the cyberspace

- somewhat intelligent agents interact with us in the cyberspace

The cyberspace is a virtual world just like the physical one we live in, it is based on causality. There are two kinds of laws:

- natural law: how nature itself works

- social law: a man-made system which mimics the natural law to create social order

Gravity is an example of natural law, "you pay your debt" is an example of social law. Both of them works the same way, given some causes, some effects must happen according to the law. We use C/C++/Java/Go/... whatever you like to describe it. From ray tracing algorithm, word processor to the e-commerce platform, it is more or less the same about baking some rules into the system. The "law" need to be static and predictable, like cement, builds the real world.

On top of the cyberspace we built, we as human interaction with each other, from social network to trading. The role played by the human is increasingly replaced by artificial intelligent agents we wrote. For example, instead of editors pick the content, it is the robot that is generating the news and preparing the homepage for you. The agent is getting more and more complex, someday they will emerge from cyberspace to physical space.

The two kinds of code work very differently. The cyberspace derives cause to effect to maintain natural/social order. The intelligent agent gathers effect to infer a model to maximize some objective. It is crucial to distinguish the intelligent part from the rest of the system. We as human need the rules to be static to build stable expectation. If the "law" keeps changing, the cyberspace will be like a "magical" place which lose the connection with our experience in the real world.

The model, the view and the control is the cyberspace. Human and robot are the intelligent agents. The model maintains the data integrity according to the causality defined by the natural or social law. The view and control provide an interface to human/robot for their convenience.

Ownership == Authorship

The cyberspace part is still too large. It is normally multi-step business process. For example

And bounded contexts correlate with each other. For example

The problem of accountability originates from the programming language we use does not cover the whole causality chain. We can draw a flow chart on the whiteboard as a whole, but we have to break it down into many small services/functions to implement it. The workflow engine is frequently brought up because it mapped so nicely to the problem domain, but BPMN is not a programming language.

There is strong causality between the steps. The promotion displayed on the product detail will need to be displayed in the shopping cart, will be displayed in the checkout, and will be applied to the final receipt. The "function" we use, can only be used to describe casualty within 500ms time span. We have to chop the process into small steps, or into different services serving users of different roles, the causality is hidden inside the messy implementation. The software runs like a relay match, one service pass on the responsibility to another. Ideally, the code should reflect the flow chart, read like the flow chart.

To make it worse, there is no hard line on who should do what, which frequently leads to debate on responsibilities between teams. Highly political environment makes developers unhappy. Meanwhile, ironically there is no one can be accountable for the whole thing when things go south, as everybody just cut a small piece from the whole.

The current best practice to fix this problem is to put a facade team on top of everything. "Ownership = Authorship", we are only willing to own what we write. This is human nature. To give these guys a sense of ownership, we allow a thin proxy/wrapper or orchestration service to glue micro-services back. This often will lead to low autonomy.

The ideal programming language should provide "function" to describe the business process. Several concurrent causality chains will correlate with each other by message passing. This way, we can assign a separate software team to every business process. They can be 100% accountable for what they are responsible for. Together with the human operator and robots as one team, be responsible for loss and be responsible for the gain, instead of being a shared cost center.

Unit of Collaboration

There is one more thing that is broken. The module unit provided by the language, such as assemblies/packages/classes used to be the unit we collaborate with each other. This is no longer true. Software modules need to be versioned and deployed separately to support multiple teams working independently.

But do we "always" need to use different language with different tools for different microservices? The language difference and disconnected tooling make the cross-team communication even harder. You can own your process, own your service, but that should not stop you from sharing the same language with your buddy fellows. One programming language plays 3 different roles: it connects the machines, the developer and the team. Today, the programming languages served primarily as tool to connect machines with people, leaving teams disconnected in the big picture.

The solution should think the software as a whole, instead of being limited by the narrow view of single "os process". The cost of introducing a new micro-service should be as cheap as starting a separate thread backed by function in a separate package. The ideal programming language should not treat all function calls evenly.

Top comments (0)