Computers are inherently not good at randomness. The thing is, you can program a machine to generate numbers which may be considered random, but the machine is at the mercy of its programming. You cannot really call something truly random if it follows an algorithm to generate the random numbers.

Truly random numbers can be generated but they usually rely on unpredictable physical processes which are not defined by man-made patterns, e.g. based on thermal noise or nuclear decay of a particle. Random.org, for example, generates true random numbers from atmospheric noise. These are used in casino games, and lotteries to make them unpredictable.

Pseudorandom numbers

Programming languages and libraries provide procedures to generate what we call pseudorandom numbers. These algorithms generate a sequence of numbers approximating a truly random sequence. For most applications, these pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) are good enough.

Typically, a PRNG would start with a seed — a number that forms the starting point of the random sequence, and subsequent numbers are generated from there. So if you always start from the same seed, you will always get the same sequence of numbers.

Auto seeding pseudorandom number generators

Most libraries and languages will provide an interface for you to specify the seed to generate a sequence, but they will usually default to automatically selecting a seed.

JavaScript for example, does not let you specify a seed for Math.random() and crypto.getRandomValues(). Each invocation of any of these methods produces a fresh unpredictable random number which is not reproducible across runs. This is great, right? Yes, but there are cases where controlling the seed is desirable.

Need for Seed 🏎

Being able to specify a seed for a PRNG has several use cases, but they could be generally described as cases where the state is tied to the random sequence. Here are some examples:

- A generated graphics object or a data structure. There may be several cases where the object instance needs to be recreated (or repainted in the graphics world). You want the object to be the same every time the function is invoked for that instance. e.g. Consider this sketchy circle which is generated using a set or random points. If this instance of the circle is drawn on a canvas

ntimes, each rendering should look the same.

Simulations & Testing frameworks — sometimes you want to replicate a test in different environments and you may want to replicate the exact test run in those environments. Same goes for simulations - simulating certain physics systems or processes repeatedly.

Gaming — The environment in a game (world/scene) is often generated with some randomness, be it terrain artifacts or locations of hidden gems. When a player returns to a game after saving it, you would want the generated world to be the same as when they left it.

Seeding in JavaScript

When the language or the API does not give you a way to seed your random numbers, as in JavaScript, you need to create your own PRNG. There are many out there. Here's a very simple one, even though it may not be the best one:

class SeededRandom {

constructor(seed) {

this.seed = seed;

}

next() {

return ((2 ** 31 - 1) & (this.seed = Math.imul(48271, this.seed))) / 2 ** 31;

}

}

// To create a random seed:

function createNewSeed() {

return Math.floor(Math.random() * 2 ** 31);

}

There's a TC39 proposal to add seed based random number generation in JavaScript, but there doesn't seem to be much activity going on 🙁

Things to consider when using seeds

When seeding, you are usually creating some artifacts using the generated random numbers.

These artifacts should be the same for the same seed value.

Maintain the order

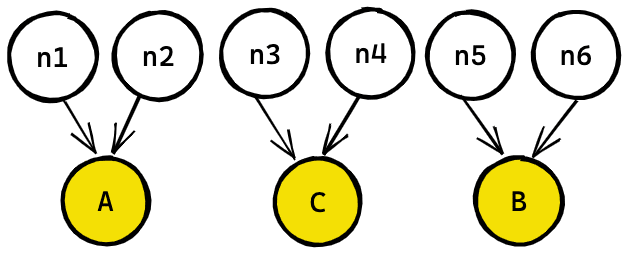

Let's say you need to create three artifacts from a seed: A, B, C and each requires two random numbers.

The sequence of numbers will always be deterministic, so if the artifacts are generated in a different order, you will not maintain the consistency you need.

Constant bits and Dynamic bits

There are times when you use a seed to create an object, but the next time around you may want the same object but with slightly different attributes. This may sound vague, so let's look at a specific example: You use random points to create the edges of a polygon and fill the polygon with more random lines. Now you want to scale this shape up. When doing so, you can use the same seed to maintain the general shape of the polygon; but to maintain the density of the filled lines, you need more lines.

The simple rule here is to figure out which bits of your object remain constant, and which ones don't. Always create the constant ones first so you always use the same sequence of numbers for the constant bits. This scenario is not specific to graphic shapes of course.

Back to the polygon example, consider a sequence of random numbers for a specified seed N1, N2, N3, ..... Say you need k random numbers to draw the outline of the shape. Then you use more numbers unti Nl to fill the shape.

When you scale this shape up, the value of k remains constant, and you may now have to go upto Nm to fill the larger shape.

Sub-seeding

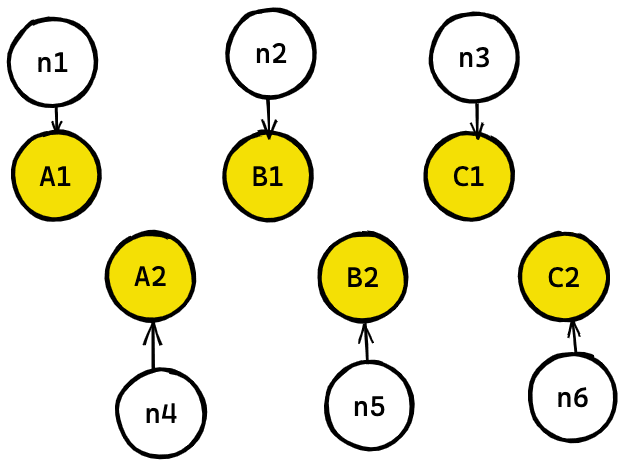

Consider an object that needs to maintain two parallel sets of artifacts. A1, B1, C1 and A2, B2, C2, each artifact requiring a random number. These can be generated in two ways. A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2 (interleaved method) or one segment at a time A1, B1, C1, A2, B2, C2 (sequential method).

Both these methods will generate the same object every time because the assignment of the random numbers is fixed. But let's say you want to add a fourth artifact while maintaining the values of the previous artifacts.

Only the first method of interleaving parallel artifacts maintains the values of A, B, C when D is added. (More specifically, notice that A2 is always associated with n2 in the interleaved method, and gets associated with n4 or n5 in the sequential method).

So you might say, always interleave in situations like this. Which is great, but there are cases where it may not be possible. Limitations of the design may lead to situations where computing A2 may not be possible before computing A1, B1, C1, D1.

One strategy for dealing with this is creating a new seed that is a deterministic value derived from the original seed. I'm going to call this method sub-seeding. With this new sub-seed, you create a new sequence of numbers that is still determined by the original seed.

Creating a sub-seed could be a very simple function, e.g. subSeed = seed + 1. Now you have two independent sequences of numbers determined by a single seed associated with the object.

Top comments (1)

Thanks for posting. You have done a very good job so far. Carry on!