Periodically, I find myself repairing old computer equipment. IDE format hard drives are no longer produced, and optical discs serve as consumables — not all older laptops and desktops can boot from USB, and buying blank CDs or DVDs in packs or individually can be quite costly. Therefore, the most popular classifieds board on the internet and flea markets serve as a treasure trove of parts and consumables for me. There, for mere pennies, one can acquire used rewritable CD/DVD-RWs, and also old hard drives that can still be of service to new owners. But this isn’t about how to save on components; it’s about what one can sometimes find on these ‘second-hand’ storage devices…

I’ve always been amazed by users who carelessly dispose of their files, throwing them away along with their storage devices. It’s pretty clear how hard drives and blank discs end up on the flea market: traders at these markets find them in the trash and then sell them to anyone interested, like me. The question of whether a new owner of a legally purchased disc can freely use the information stored on it remains a topic of debate. However, buying used storage devices implies that they are sold “as is” by the vendor. This means with all possible defects and data, which could potentially be dangerous if, for instance, the disc contains a malicious virus or a lurking Trojan encoder. Moreover, there’s no way to test the functionality of a hard drive at a flea market — it’s always a gamble. However, they are inexpensive, so the risk is often justified.

With rewritable optical discs, the situation is generally straightforward: in ninety percent of cases, they contain movies. The remaining ten percent usually hold photographs or software. I typically erase the contents of such discs right away because looking at someone else’s vacation photos is quite a dubious pastime, while the space on the disc could be used for something genuinely useful. However, once I found a 1997 address and phone directory on a Compact Disc and surprisingly came across my own name, listed at an address that no longer exists.

Hard drives are much more interesting. I usually skim through their contents in search of rare old software and games, not all versions of which can be found on the internet, as well as useful drivers for outdated equipment. If the previous owner didn’t bother to delete the information, personal files also turn up. For instance, I once bought a 2.5” terabyte external hard drive at the market for 3 dollars with the seller’s note: “defective, won’t power on.” True enough, the drive wasn’t recognized by the computer when connected (probably the reason it was discarded) due to a broken contact in the box. After resoldering the contact, the hard drive miraculously came back to life.

Apparently, the hard drive previously belonged to an employee of one of the European banks. I deduced this from the fact that the folder “Collateral Property” contained a vast number of scanned copies of documents — passports, driver’s licenses, vehicle registration certificates, and technical passports. Also found were several databases and documents related to the former owner’s divorce proceedings (including copies of real estate ownership papers and scans of both national and international passports). Additionally, there was a separate folder with files titled “psychologist’s advice: how to quickly forget an ex.” It’s frightening to imagine what could have happened if this “treasure” had fallen into the hands of criminals or fraudsters. Of course, I immediately formatted the disk and destroyed all data on it, but this case can serve as a clear illustration of how risky it is to throw away a storage device, even if it appears to be broken.

Here are a few other interesting finds I’ve discovered on second-hand hard drives that I bought at the market or through ads on eBay:

- A large text document aged fifteen years containing passwords (it even had details for an account on the once-popular messenger ICQ). I didn’t check if the passwords were still valid.

- A complete set of PHP scripts for a small company’s website, including the backend, frontend, and MySQL database. Interestingly, the site still exists online, albeit with a different appearance now. Had I been a hacker, I would have definitely analyzed the scripts and database for vulnerabilities and sensitive information.

- Distributive of commercial software with serial numbers. It’s uncertain if the previous owners of the disks obtained these programs legally, but the presence of serial numbers and key files theoretically allows someone to install, activate, and use such software. However, this would also be considered piracy.

- Recordings of online webinars on financial literacy and investments. Watching a few lessons didn’t make me a billionaire, but a quick Google search revealed that access to these courses is actually paid and quite expensive.

- A plethora of music across various styles and genres, as well as electronic books in fb2 and EPUB formats. There’s too much to read and listen to. On one disk, I found a collection of guitar samples and partially mixed compositions — apparently, the disk once belonged to a musician who practiced studio recordings.

On the hard drives that passed through my hands, I also discovered various medical documents (presumably, one of them once resided in the computer of a clinical laboratory) — including patient test results. Doctor-patient confidentiality? Apparently unheard of. Coursework, essays, lab reports, and diploma projects are commonly found too (in fact, a hard drive from a former student’s laptop is a treasure trove of such educational content). On one hard drive, I found a dozen folders with intriguing names like “Video Home [Date]”. This disk seemed to have been used in a home surveillance system recorder, as all the videos saved in these folders showed the same dreary apartment. The most interesting thing I found in these recordings was a permanently sleeping fat lazy cat on various furniture items. And, of course, there are fragments of someone’s personal life in the form of photographs, documents, saved web pages, and phone numbers of friends and relatives.

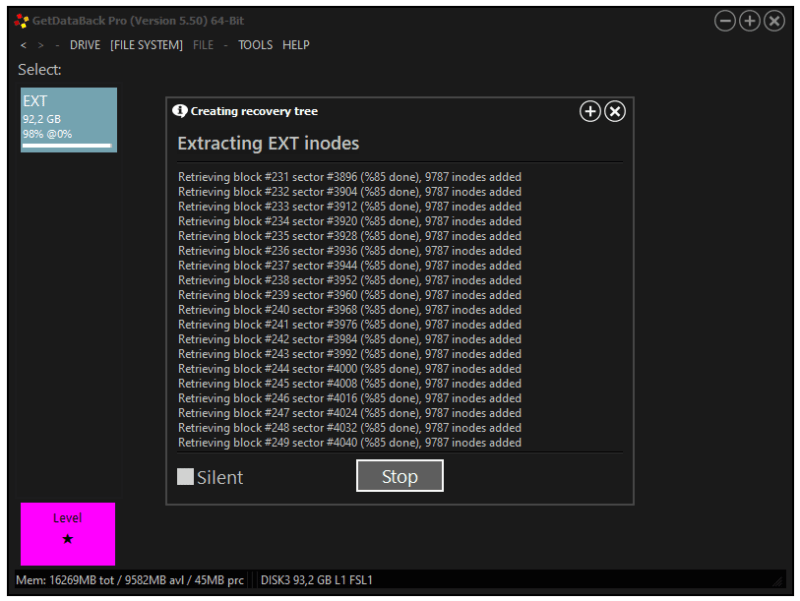

Even if you delete all files or format partitions on a hard drive before tossing it into the trash, it’s not guaranteed that someone overly curious won’t be able to access the data stored on it. In Windows OS starting from Vista, complete (not quick) formatting of a disk is done differently than in XP, meaning the information on the disk is actually overwritten with zeros, making it challenging to retrieve lost data from such a partition. Nevertheless, there are many relatively easy-to-use programs for different operating systems designed for recovering deleted files and information. Perhaps the most well-known among these is the Windows utility GetDataBack, which allows for file recovery on NTFS, FAT, exFAT, EXT, and other partitions. There are also alternative programs that scan the disk for fragments of remaining files, such as R-Studio and EasyRecovery. Moreover, on Windows, you can even recover deleted items using PowerShell commands. However, I usually use GDB due to its simplicity and convenience: you just launch it, select the information search mode, and then go drink coffee while the machine quietly whirs away with the hard drive.

Recently, I purchased a small stack of rare laptop hard drives ranging from 40 to 100 GB on a classifieds website. All the disks I bought didn’t contain any data, but out of pure curiosity, I decided to conduct an experiment: run them through GDB and see if the program could find any information that had previously been on these carriers.

So, I did just that. I tested five disks, and here are the results I got. On one, I found a previously installed Windows XP — the application showed folders like $RECYCLE.BIN, System Volume Information, and directories of user accounts. However, there was nothing particularly interesting to be found there.

On the second hard drive, I found nothing intriguing besides the standard System Volume Information and Lost & Found folders. Scanning the third disk yielded a bunch of Microsoft Word documents, most of which couldn’t be opened due to corrupted content. The others were rather dull descriptions of construction materials and office partitions. I found some previously deleted images, though a significant portion was damaged. The remaining were phone-copied photos — water meter readings, some celebrations, and fishing. Apparently, the files were simply deleted, and the disk wasn’t formatted.

Another disk had been used for Linux — GDB recognized the EXT file system, but I couldn’t extract anything useful like /etc/passwd. Finally, on the last disk I examined, there were traces of a Windows 7 installation, judging by the presence and structure of service partitions. However, as it was a system disk, it seemed to hold nothing of value.

In conclusion, from the five hard drives I purchased and examined, I was able to retrieve user files from just one. The most valuable finds were a fitness center class schedule and a photo of a happy man with a kilogram-sized pike. However, if instead of a fish, the man had stored a cryptocurrency wallet packed with Bitcoins and its password on this disk, life might have suddenly become more colorful…

What lessons can we take away from my story? They are, in fact, quite simple and obvious: merely deleting files and quick formatting is usually not enough when disposing of or selling hard drives. For more assurance, it’s better to perform a full format (in modern operating systems, of course). And for the truly paranoid, there’s the good old console utility SDelete from the Sysinternals suite or a tool named Darik’s Boot and Nuke (DBAN).

Encrypting disk partitions using standard Windows tools or third-party utilities that place data in encrypted containers (which can be mounted to the system as a logical drive) offers good protection for information. For example, if files are stored on a BitLocker encrypted partition, a quick format is enough for their secure deletion: this destroys the cryptographic key, making subsequent access to such information impossible. However, the BitLocker key might accidentally be found somewhere else, like in a OneDrive cloud storage linked to your account. Nonetheless, many avoid using BitLocker and other encryption tools, fearing system performance degradation.

In any case, it’s not advisable to just throw away used optical discs and hard drives in the trash, even if the latter are faulty. Dumpster-diving enthusiasts will retrieve them and bring them to flea markets, where someone like me might buy such a hard drive for a couple of dollars. Personally, I never use any information I come across for reprehensible or illegal purposes, but people are different. Someone might be tempted by a file with passwords or scanned copies of documents found on the drive. Of course, most serious services on the internet now use two-factor authentication, but it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Even if someone ends up perusing your beach photos and reading your private chats, there’s little pleasure in that. Personally, on my old disks, I delete the logical partitions, then recreate them, and for added security, I fully format them. Faulty hard drives with personal content are taken to my summer house and baked in the coals along with marshmallows. After such thermal treatment, nothing survives on them — not even viruses.

This article is written by Techical Editor Valentin Holmogorov and supported by the Serverspace team.

Serverspace is an international cloud provider offering automatic deployment of virtual infrastructure based on Linux and Windows from anywhere in the world in less than 1 minute. For the integration of client services, open tools like API, CLI, and Terraform are available.

Top comments (1)

Thats what I am doing with my old laptops hard drives now 😂

Jokes aside, a very nice article, and I learned quite a few things from it.