Validation can mean a lot of things, but in API land it generally means figuring out if the data being set to the API is any good or not. Validation can happen in a lot of different places, it can happen on the server, and it can happen in the client. Traditionally client-side and server-side validation have both played a role, covering different use-cases.

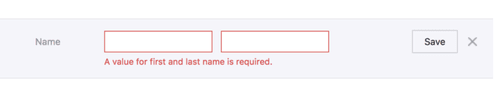

Client-side validation is generally used to very quickly provide feedback to a user, to do things like highlighting the input box that failed, with red outlines, tooltips explaining that the email address doesn’t look valid, explaining that the “Amount to pay off your credit card” should be higher than 0, etc. These days browsers take care of a lot of the visual feedback so often client-side validation is not doing quite as much as it used to, but it is still required for “either field A or B should be set, but not both, and if B is set, we C should be too.” sorts of thing.

Server-side validation has always been required and for an API is the most important of the two. An API that relies entirely on the client is going to end up with problems. Data coming from the client can never be trusted because it’s impossible for the server to know what happened on the client. Even if you’re developing a private API for only two known clients, there are always chances that validation in those clients breaks down; or someone will hit those APIs with curl or Postman and send some invalid stuff. Even if the database catches invalid data, the errors won’t be useful.

Writing validation rules has always been a major source of pains in my… neck, for the last 15 years, so an approach to syncing the two has forever been on my mind.

API Description Documents

Server-side validation is usually doing the most mundane of tasks.

- Is this property required

- Is this property an email address

- Is this property a credit card number

- Is this property required if other property is present

Some frameworks shove this logic in the controller, which is a pain when you need to validate the same payload in two different use cases. Others shove it in the data model, like Ruby on Rails:

Doesn’t this all sound incredibly familiar? This is exactly what API description docs (also known as specifications) are talking about, required, types, formats, etc… all of this is already handled for us entirely by the same API descriptions we used to generate our mock servers for trial integrations, that we wrote to get beautiful reference docs, that we are using to manage our API Gateway, etc.

Some of you may have read our article a while back about using JSON Schema for client-side validation, and now we want to show you how to leverage your existing source of truth for drastically reducing the amount of validation code you need to write server-side too.

Which Description Format

OpenAPI and JSON Schema are the two biggest API description formats, and there are a lot of options for all the programming languages.

OpenAPI tools are listed on OpenAPI.Tools and JSON Schema has a whole huge list on JSON Schema: Implementations.

JSON Schema Example

JSON Schema is not aware of metadata like URLs or HTTP methods as its designed to work with any JSON data instance. In API land the JSON data instance we’re most likely to work with is the HTTP request body or the response body.

For example purposes we are gonna make some JSON Schema validation happen in Node.js, but you can use any language that has a JSON Schema Validator (which is most of them).

To use JSON Schema for server-side validation, you normally just grab one of the validators, shove it in your controller, or “routing” or whatever your language/framework of choice calls it. Using Express.js, we can put this logic in our route.

A fairly familiar app.js to Node users, we are just requiring a few bits of code, and loading the userSchema.

That userSchema file comes from schemas/user.json which you can make locally, and will have contents like this:

When you inspect the structure, you can infer that our JSON object has the following list of properties: name, email, and date_of_birth. The first two are strings, and the third is a date. Also, name is marked as required.

Now we can run this Node app with node app.js and fire HTTP requests at it:

$ http -v PUT http://localhost:3000/123 name=Frank

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 14

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Date: Sat, 25 May 2019 08:09:10 GMT

ETag: W/"e-4o7E1rWH1O+7xJOCXIMFqIbMSxE"

X-Powered-By: Express

that was great

Ok it liked that because name was set but email and date_of_birth are optional. Let's try sending them, but bad.

$ http -v PUT http://localhost:3000/123 name=Frank email=notanemail

HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

Connection: keep-alive

Content-Length: 164

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

X-Powered-By: Express

{

"errors": [

{

"dataPath": ".email",

"keyword": "format",

"message": "should match format \"email\"",

"params": {

"format": "email"

},

"schemaPath": "#/properties/email/format"

}

]

}

Oh no! Some errors happened. Sorry!

These errors are not the best format because we just dumped them out for demo purposes, but this can be tidied up with a simple helper.

If you were already doing validation in the controller, then your controller should be a lot cleaner, and if you are doing extensive validation in your model then this will remove a lot of the cruft. If you did not have validation before, then using this approach means you don’t need to start writing it. Win win win!

Also, whilst this works in any language, Ruby folks using Rack (therefore anyone using Rails too) can use committee, a fantastic middleware for making this a bit easier.

JSON Schema is pretty good at handling request body validation, but having to put this in every controller can be a bit annoying. OpenAPI can help us out here.

OpenAPI Middleware Example

OpenAPI can be a bit easier to implement here, due to it covering the service model too, not just the data model.

openapi: "3.0.0"

# ... snip ...

paths:

/pets:

post:

description: Creates a new pet in the store

operationId: addPet

requestBody:

description: Pet to add to the store

required: true

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/NewPet'

responses:

'200':

description: pet response

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Pet'

Seeing as OpenAPI will say “this schema should be used for this combination or HTTP Method and Path” you do not need to provide the glue. Instead, many languages offer tools that let you just register a middleware, tell that middleware which OpenAPI file to use, then job done.

Sticking with Node/Express for the examples, let’s take a look at using OpenAPI and registering a middleware:

Tadaaa! You don’t have to put the validation checks in all the routes, because the middleware can handle that for you, and your route/controller code won’t even bother getting invoked if the request coming in is invalid. The framework middleware is able to look at the request, compare it to the API descriptions, and reject it with an error format (hopefully something like RFC 7807) before your code even needs to wake up.

There are a decent number of options out there, but there should be more:

For OpenAPI v3.0:

- PHP: openapi-psr7-validator

- Node.js: express-swagger-ajv-validator / express-openapi-validate

- Ruby/Rails: committee

- Perl: Mojolicious::Plugin::OpenAPI

For OpenAPI v2.0:

- Rails: swagger_shield

The Rails tool swagger_shield is great. It wins maximum “Wont Hate Points” for using RFC 7807 on failure:

{

"errors": [

{

"status": "422",

"detail": "The property '#/widget/price' of type string did not match the following type: integer",

"source": {

"pointer": "#/widget/price"

}

}

]

}

Some Validation Still Required

This is only going to handle validation rules which do not require looking in a data store, or need some other sort of programming to run. You can do rather a lot with JSON Schema or OpenAPI, but it cannot tell you if the email address is valid, or if this resource is generally in the right state to be doing the thing you are trying to do.

Not a problem. You can still perform your own checks after this validation is done, and because everything is all using RFC 7807 the whole way through then your code and the middleware and everything else will all match. Lovely!

Testing Benefits

There are two huge benefits we have not quite got to yet, beyond the time and money saved from not having to write out a bunch of validation code.

The whole idea of trying to keep docs in sync with code goes out the window when your description documents are literally code.

Seeing as you are using the same description documents to handle request validation that you are using for your documentation, mock server, etc, there is no need for extra logic to ensure your requests are correctly described (or documented). You can just do your usual integration testing on requests, and you are all set.

expect(goodApple).to.be.jsonSchema(fruitSchema);

Your test suite handling bog standard unit and integration tests are now proving your documented requests are correct, and if somebody changes how requests work without updating the description docs, they’ve been caught in the act and their pull requests will fail. If they update the description in the pull request to fix the tests, boom, we can now have a little chat about why they just tried to commit a breaking change…! 🧐

Using description docs for validations only covers requests, so use the API description document to power contract testing to make sure responses are good too.

Tricking Colleagues into Writing Documentation via Contract Testing

Future of Server-Side Validation

This is a very old concept which has recently picked up steam as more developers catch onto the API Design-first workflow.

One of the benefits of writing HTTP APIs is that you usually are not locked into a single implementation, and do not have to try and force the “one size fits all” tooling that comes with it. Sadly that means some of the tools for some of the languages aren’t as excellent as others, but as we are a community of open-source developers we can fix that.

I’ve heard developers say “this is not performant” but there is no reason to believe that. A specific tool might not be written the most efficient way, but that can be fixed with PRs. So long as the tool is not parsing the entire document on the fly, and on startup constructs some sort of artifacts in memory, this could easily be more performant than running whatever behemoth of a “validation library” you’ve loaded up to do all this manually.

Another approach is to skip out on doing it in the server-side, and move it up a level: to the API Gateway. We’ll be writing more about that soon, but most API gateways are starting to get smarter about how they accept API descriptions as input, and how they use that input.

One example is Express Gateway, who added JSON Schema Validation, a project maintained by my friend and Stoplight.io colleague Vincenzo Chianese.

Summary

The days of treating descriptions like some annoying thing you have to do later to get docs are long behind us. API descriptions now come first, are used for contract testing, getting feedback on implementation, and a whole bunch of other stuff.

Use this as another carrot to convince your laggard teammates or boss that this is the way to go.

Top comments (0)