Last year, my co-contributor to Exercism.io wrote a fantastic article about writing a TypeScript code analyzer, and I wanted to follow up by sharing my thoughts and experiences writing one for Elixir.

In case you have not yet read that article, Exercism.io is a free platform designed to help you improve your coding skills through practice and mentorship.

Exercism provides you with thousands of exercises spread across numerous language tracks. Once you start a language track you are presented with a core set of exercises to complete. Each one is a fun and interesting challenge designed to teach you a little more about the features of a language.

An initiative was started in 2019 to incorporate automation into the mentoring process to improve the experience for students of each language. Automated feedback means faster responses, which means greater student satisfaction.

Over 500,000 people have used Exercism and have submitted 1.5 million submissions, 220,000 of which have been mentored by our volunteers. In 2019, MOSS supported [Exercism] in the creation of an automatic feedback system based on automated analysis of submissions. Since launching, [the system has] automatically approved 25,000 solutions, and generated 38,000 pre-canned comments for mentors to post, saving our [volunteer] mentors 263 days of work! -Jeremy "iHiD" Walker (Exercism co-founder)

Derk-Jan walked through the reasoning and process of writing a TypeScript analyzer. But to briefly summarize:

- Unit tests are great for testing code behavior.

- Unit tests are not suited for testing code style or code smells.

- Using static code analysis techniques allows development of automated feedback to catch easy cases.

- Removing even a fraction of work from a human mentor's workload is valuable to both the student and the mentor.

As I set in to write Elixir's analyzer, it occurred to me that it is really hard to write good static analysis tests.

Table of Contents

- Analysis is hard...

- A new strategy emerges, Pattern Matching

- Searching through code

- Creating a language to describe the tests

- Putting it together

- Conclusion

Analysis is hard...

...because of normal variation

Code, like language, is expressive and creative. It allows people to write the same things in many ways to express slight differences in meaning and usage. Let's look at a JavaScript example before moving into Elixir, as it illustrates the point clearly:

export function name() {}

// FunctionDeclaration

export const name = () => {};

// ArrowFunctionExpression

export const name = function () {};

// FunctionExpression

export default {

name: () => {},

};

// ExportDefaultDeclaration + ObjectExpression + (Arrow)FunctionExpression

Here are 4 ways to write the same thing: an exported function declaration. So analyzer tests have to account for normal, acceptable ways to write clear, concise code according to the values of the person writing the tests (Sometimes this is 'idiomatic' code; often it comes down to personal choices and beliefs about programming), which is why static analysis is often done on a represented intermediate form, such as an abstract syntax tree.

An abstract syntax tree (AST) is a representative form of the code often used as an intermediate form for compilers to perform optimizations and transformations of the code without worrying about how code is formatted.

Okay, leaving JavaScript behind, let's look at Elixir.

...because AST syntax is complex at scale

Abstract syntax trees, at their most basic, take only a few shapes in Elixir:

# Suppose we had the function:

sum_three = fn a, b, c -> a + b + c end

# And we used it like this:

sum_three(1, 2, 3)

# The underlying AST that represents this function call is:

{:sum_three, [], [1, 2, 3]}

The first element of the tuple may be an atom or another tuple. The second element is a list of metadata (often line numbers when read from a file). The third element is a list of the arguments. We can get the AST of any Elixir code using the quote/2 macro:

iex> quote do

...> 1

...> x = 2

...> 3 + x

...> end

{:__block__, [],

[

1,

{:=, [], [{:x, [], Elixir}, 2]},

{:+, [context: Elixir, import: Kernel], [3, {:x, [], Elixir}]}

]}

In the AST form, this code quickly loses meaning for the observer.

But, like the TypeScript Analyzer, why not use a standard such as ESTree, in order to build upon semantic meaning and abstractions? Sadly, it is because such a library does not exist in the Elixir ecosystem.

A new strategy emerges: Pattern Matching

Since much of static analysis is looking for patterns in code, Elixir's core strength is the ability to use pattern matching. Pattern matching can be used to compare the shape of data without knowing the actual data:

_ = [1, 2, 3]

#=> [1, 2, 3]

[_] = [1, 2, 3]

#=> ** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: [1, 2, 3]

Here are two examples. In the first, the underscore (_) is used to say “we don't care what it is”, but only are concerned that we have 1 thing on the right side of the match (IE: 1 list of integers). In the second example, we declare we want to match a list with a single element. The right-hand side does not match this shape and as a result it raises an error.

So applying this to the AST problem:

To write a test to ensure a student wrote a piece of code, we could look for a pattern match based on the desired shape of the code without knowing all of the other implementation details!

# Does a student bind any value to x?

def test(quoted_form) do

{:=, [], [ # The match/bind function

{:x, [], Elixir}, # The x variable

_ # The any-value being bound

]} = quoted_form

true

rescue

MatchError -> false

end

quoted = quote do

x = 3

end

#=> {:=, [], [{:x, [], Elixir}, 3]}

test(quoted)

#=> true

How powerful! Now, a student may choose any value to bind to x, and we can find this pattern in the AST!

Searching through code

But Exercism doesn’t consist of one-line problems. Problems, like TwoFer, can be very simple, but require at minimum several lines of code.

# Sample solution for ‘TwoFer’

defmodule TwoFer do

@doc """

Two-fer or 2-fer is short for two for one.

One for you and one for me.

"""

@spec two_fer(String.t()) :: String.t()

def two_fer(name \\ "you") when is_binary(name) do

"One for #{name}, one for me"

end

end

Writing a test like we did before to account for every variation would be very hard. Someone might rearrange statements or expressions and the test still has to work.

If this solution is converted to an AST, the Elixir Macro module provides functions that can be used to search through the tree. Macro.traverse/4 is a generalized function that will walk through the generated AST, maintain an accumulator, and apply a function to the node before it walks further down the tree, or after it returns, on its way back up the tree. We only need an accumulator (to track the status of our tests) and a function to test on the way down the tree, so it is simpler to use Macro.prewalk/3 instead.

By using function from the Code Code module, the file can be read into a string, then converted to a quoted form:

"code_file.ex"

|> File.read!() # read the file to a string

|> Code.string_to_quoted!() # create the AST

|> Macro.prewalk(false, fn node, matched? ->

case matched? do

# if it already matched, propagate

true ->

true

# test the node for a match

false ->

test(node)

end)

Creating a language to describe the tests

Despite having an approach and a method, testing was still very hard to accomplish, because writing AST-patterns is very complex and error-prone. A single bracket changes the meaning of the AST, causing either false-positive or false-negative results. And this being an automated system, issuing errors when nothing is erroneous is unacceptable and would likely frustrate a student, possibly causing them to give up.

We have all been there, minding our own business filling out a form on the internet when a wild error appears! You try to troubleshoot it, but the error persists. Frustrated, you abandon the website, never to return.

So making tests easy to write and understand for a maintainer is a priority. So what if we wrote a domain specific language to describe the tests declaratively?

A domain-specific language (DSL) is a computer language specialized to a particular application domain. -Wikipedia

Elixir can do this! With metaprogramming you can write macros that transform and generate code at compile-time, so that it has a specialized behavior at run-time.

Designing the DSL

The goal is to have a declarative syntax to write our test, so let's look at ExUnit, Elixir's batteries-included test suite, to see if we can find some features to emulate:

test "addition" do

assert 1 + 1 == 2

end

In ExUnit, we have a keyword test, which calls a macro, which then uses the string, "addition", to create a function with the contents of the do-block, which is then executed at run-time. So let's use this inspiration to dream up a specification for static analysis.

For our static analysis pattern matching tests, we’d like to:

- Label the test with a name

- Be able to specify if the test should be run or skipped

- Decide what to do with the solution if the test fails

- Return a message to the student, preferably with an actionable step

- In our case, we will write a separate markdown comment, and display that

- Further specify the conditions where in the code this pattern should be found

- Like if it appears at the top-level, or nested in code (depth)

- Be able to write regular Elixir code to define the pattern

- Be able to ignore certain parts of a pattern, so that we can generalize the pattern to match

After a lot of wrestling about names and conventions, the DSL eventually became this:

feature "has spec defined" do

status :test # :skip

on_fail :info # :disapprove, or :refer

comment "Path.to.markdown.comment"

find :all # :any, :one, or :none

# depth <number> # optional

form do

@spec _ignore # the pattern looks for a @spec module attribute

end # but doesn't need to match the contents

end

The find keyword is used as tests become more complex. Multiple form blocks can be declared for a test, and you can specify how it will use those blocks to match.

Writing the macro

In Elixir, a macro is similar to a function definition, but it can only be used in certain circumstances:

- The module containing the macro must be imported using

requireto opt-in. (There are some ways to get around this, but in general this is true) - The macro must be defined before it is used (it isn't "hoisted", to use a JavaScript term)

Let's write a basic macro for the feature call in the DSL:

# Module to contain the macro

defmodule ExerciseTest

# Define the name, arguments of the macro

defmacro feature(description, do: block) do

# do the transformation here using the arguments here

end

end

Often, we would use this macro to return a result from the transformation (like the in/2 macro), but here, we are going to use the macro to write a function using the transformation, so it can be called later. So at a high level, our macro needs to:

- transform the elixir code pattern we are looking for into an AST form in order to be able to pattern match on it

- store the pattern in a module attribute for use when called

(This code is quite involved, and not perfect! So I will be only touching on select parts, see the whole source for how it all works together)

Transforming the pattern

(See the source,

exercise_test.ex, line 66)

To recap, we want to transform a readable pattern like this:

form do

@spec _ignore

end

Into a pattern to match on like this:

{:@, _, [{:spec, _, [_]}]}

When the macro is being executed, the block that was passed to it, is transformed into the AST and has the form (with or without line number metadata):

{

:@, [context: Elixir, import: Kernel], [

{:spec, [context: Elixir], [{:_ignore, [], Elixir}]}

]

}

Two transformations need to be done to normalize the pattern:

- Remove metadata

- Change

:_ignoreinto_

Following the pattern we have already observed, we can use Macro.prewalk to walk through the AST to do this for us:

# Remove the metadata, changing it into something we can ignore

form =

Macro.prewalk(form, fn

{name, _, param} -> {name, :_ignore, param}

node -> node

end)

then

# Change _ignore into _

Macro.prewalk(form, fn

{atom, meta, param} = node ->

cond do

atom == :_ignore -> "_"

meta == :_ignore -> {atom, "_", param}

true -> node

end

node ->

node

end)

|> inspect() # AST to a string, since _ can't appear outside of pattern match

|> String.replace("\"_\"", "_") # Collapse duplicate quotes

After those two transformations we have "{:@, _, [{:spec, _, [_]}]}" which can be used as a pattern with the function Code.string_to_quoted!/2.

Storing the pattern

An interesting feature of Elixir modules are module attributes. They serve several features, but we will use them as temporary storage to pass along our patterns from the pre-compile step (where macros are expanded), to the compile step (where top-level functions are expanded).

Look at this example module:

defmodule PassItForward do

@data [] # Bind the initial empty list to the attribute

@data [1 | @data] # Rebind the attribute, building on the data

@data [2 | @data] # Rebind again, resulting in `[1, 2]`

end

Once our feature macro has made the pattern for the test, the function will store the pattern (and the other test parameters) in a module attribute to be used when creating the final test function.

(See the source,

exercise_test.ex, line 42)

quote do

@feature_tests [

{unquote(feature_data), unquote(Macro.escape(feature_forms))} | @feature_tests

]

end

Wait a second! What is that unquote function?! 🤯 For a macro to affect the outside context, it must return a quoted block. When the macro returns, it transforms the quoted representation (AST) to Elixir code. So to summarize Elixir's getting started guide: to inject the value from the variable, we use the unquote function:

# Rather than this:

number = 13

Macro.to_string(quote do: 11 + number)

#=> "11 + number"

# We want this:

number = 13

Macro.to_string(quote do: 11 + unquote(number))

#=> "11 + 13"

Macro.escape prevents the unquoted value from being altered on return.

Putting it together

We have an approach to analyze the solution through pattern matching, and with the DSL we have a way to declaratively write tests (write what we want it to do rather than how to do it). But how do we use this?

You could just copy and paste these functions into every module to be tested, but that would be unmaintainable and precarious.

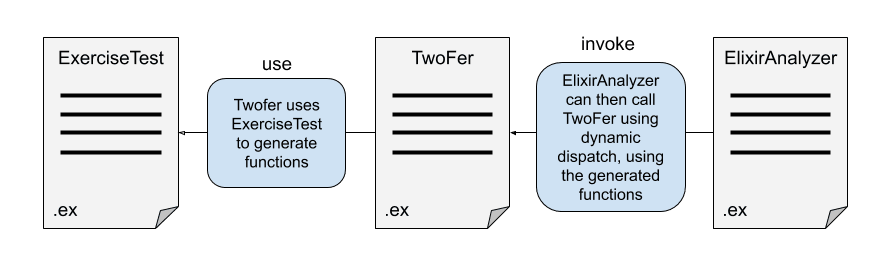

So we are going to organize our code like this:

- Organize our DSL macro function into a module (

ElixirAnalyzer.ExerciseTest.ex). - Write a module for a specific problem that contains tests to be compiled (

ElixirAnalyzer.ExerciseTest.TwoFer.ex). -

Then we will inline the macro, calling

use ElixirAnalyzer.ExerciseTest- This is a macro call to

__using__/1which then generates this code inTwoFer:

defmacro __using__(_opts) do quote do # Inline ExerciseTest into TwoFer import unquote(__MODULE__) # Call the __before_compile__ function to happen after # macro expansion, but before compilation @before_compile unquote(__MODULE__) 1 # A default flag for our analyzer system @auto_approvable true # the initial state of the module attribute @feature_tests [] end end- Just before the code is compiled

__before_compile__is called, which uses the collected@feature_teststo create theanalyze/2function

- This is a macro call to

This allows ElixirAnalyzer.ExerciseTest to generate specific inline functions in each module that calls this.

Once this is compiled, and the application is running, we can tell the application what problem is to be analyzed. We can then use dynamic dispatch to call the specific module's own analyze/2 function:

(See the source,

elixir_analyzer.exline 156-166)

defp analyze(s = %Submission{}, _params) do

cond do

# If analysis has been halted for any reason

# refer the solution to a human mentor

s.halted ->

s

|> Submission.refer()

# Dynamic dispatch call to the specific problem test module

true ->

s.analysis_module.analyze(s, s.code)

|> Submission.set_analyzed(true)

end

end

Wrapping up

We now have a system of interacting modules which compose themselves into an analyzer. An overview of the code is here:

(See the full source on GitHub: exercism/elixir-analyzer)

Conclusion

The end result is a method to produce readable analyzer tests. If they are readable, then hopefully they are understandable. If they are understandable, then they are maintainable.

Our flexible DSL should allow us to also write tests that can target specific mistakes or anti-patterns in a submitted solution.

Thanks for sticking with me through this walk through Exercism's Elixir Analyzer!

Hope to see you around Exercism!

If you enjoy programming and looking for an opportunity to learn a new language in community, check out Exercism.io! If you have programming experience in a language and also looking for opportunities to mentor and help others, come visit!

Top comments (1)

🧙♂️