I just completed taking Elisabeth Hocke’s course, The Whole Team Approach to Continuous Testing, on Test Automation University. Wow! Talk about a mind-blowing experience.

Mind-blowing? Well, yes. Earlier in my career, I studied lean manufacturing best practices. In a factory, lean manufacturing focuses on reducing waste and increasing factory productivity. Elisabeth (who goes by ‘Lisi’) explains how this concept makes sense in a continuous delivery model for software.

The Lean Factory

To learn lean manufacturing, I read a book by Eliyahu Goldratt called The Goal. Written in 1984, the book helped explain the concept of waste as building up an inventory of work-in-process (WIP) that could not be manufactured. Goldratt describes walking into a factory filled with WIP inventory that was just piling up.

As Goldratt describes the problem and wonders how to address it, he goes on a hike with his son’s boy scout troop. One member is always the slowest. When they put that scout at the end, he falls behind everyone else. When they put that scout in the middle, it becomes two groups – the fast group, then a gap, and then this scout and everyone else behind him. Finally, they put this one scout in the front of the troop, and everyone stays together.

Goldratt describes the ‘aha!’ moment of realizing that the slowest process in the factory limits the speed of the factory. Everyone else might be busy building body parts or electronic harnesses, but if some step further in the assembly process can’t consume those parts as quickly as they are made, they build up waste.

Goldratt concluded that the efficient factory designs its process to make products at the pace of the slowest process – that profitable operation creates finished products and not waste.

Continuous Delivery As Lean Factory

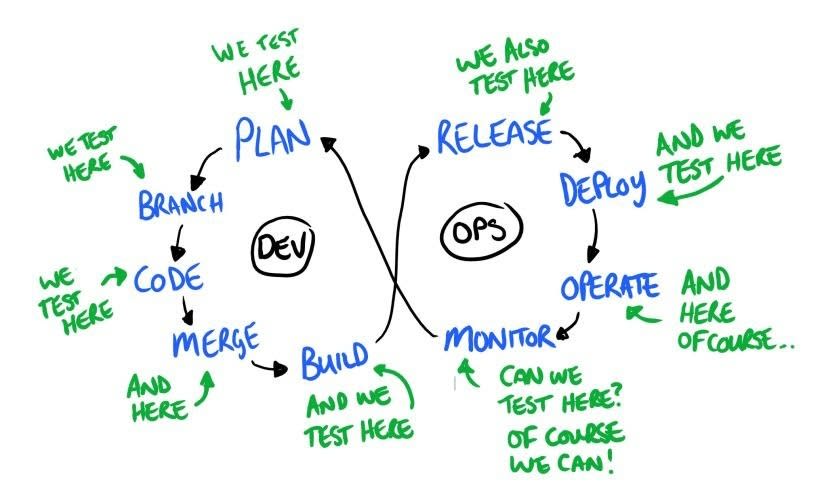

Lisi spends the first chapter delving into the definition of continuous testing in the framework of continuous delivery. She quotes industry thought leaders like Bas Dijkstra, Jez Humble, Dave Farley, and Dan Ashby to get to some key ideas – namely, that continuous testing means ensuring that you are testing at every step in the continuous delivery process. She even shares this image from Dan Ashby:

This diagram shows continuous delivery in a DevOps model with testing everywhere.

Lisi makes the key point – success in continuous delivery means shortening feedback loops to learn early. Every point of development and delivery needs validation.

- In planning – how do you test your plans? How do you validate what you’re up to?

- In branching – how do you make the choice about branch design?

- During coding – well, is it more than unit tests? And who runs the tests?

- In the merge – what are you testing?

- Etc.

She focuses on the key idea that at each step you make choices and want to know if those choices work. Every choice has consequences. Which designs work? Which design choice provides you with optimal results? How do you validate the performance impacts of a certain design choice? All of these questions result in choices you can test.

If you are a test professional and not in this system, you must be wondering what this means for your role. As in – what kind of testing can you do without code to validate? Or, for a developer, how can anyone test code before code completion?

Lisi walks through examples that turn you from coder or tester to scientist. Everything you do becomes a test. You can run large tests or small tests – but test early and learn to get test results early.

Unproductive Work As Waste

I brought up the lean factory because Lisa raises a lean manufacturing concept in her description of work in a continuous integration project. Lisi describes waste as the enemy of continuous deployment.

Any work that fails to deliver value involves waste. In a factory, work that creates unfinished parts faster than the delivery of finished goods creates waste. Usually, you see waste as piled up inventory. In software development, your processes can also create waste. Usually, though, the waste comes in the form of code in a “dev-complete” state – simply waiting to be tested. But, there are other sources of waste – uncoded designs, and unmerged code that are work that cannot be turned into the next step

And, with that, we come full circle to the application team. Does your team divide the coding responsibility from the verification skill set? Do you create mini waterfalls? Or, do you build a team that tries to do something different – to reduce waste in processes, to deliver quality in software, and to deliver products more quickly to market at the pace of the team?

Whole Team Testing For Agile Software Delivery

Here, Lisi turns to the Whole Team testing approach, which becomes a way of thinking about making the entire team responsible for delivering a finished product.

Lisi uses this quote from Lisa Crispin and Janet Gregory from their 2009 book, Agile Testing: A Practical Guide for Testers and Agile Teams:

“…everyone involved with delivering software is responsible for delivering high-quality software.”

Lisi gives examples from her own career to back up this idea. Her own team had gotten bogged down in undelivered code, error tickets, and general frustration. They tried the lean approach for software – “stop starting and start finishing.” Everyone pitched in to help – no matter what role they held. People helped code, test write automation. People helped the product owner – or another product owner. The team worked to finish what they had started.

As a result, Lisi’s team built up trust and broke down barriers. While expertise might exist in pockets, they realized that delivering software required knowledge sharing and growing as a team. Testers know how to test software – but they cannot be the only people writing tests if the team hopes to deliver effectively. Lisi explained that, once the team had collaborated together once, they were prepared to do it again.

So, Lisi asks us to think about our own teams and how we build and share knowledge. We might have silos. We might only have a single test automation expert. She contrasts that with her teams, which work to share knowledge and focus on getting things done.

Her course offers lots of resources to help you move to a more team-oriented approach. One of those is the set of courses on Test Automation University, which can help you increase your team’s skillset in automated testing.

Organizing Your Team

Lisi spends three chapters talking about organizing your team for success.

Working Solo

First, she looks at organizations where everyone ‘works solo.’ Individuals do their own tasks and try to be as productive as possible. Tremendous amounts of specialization. Plenty of opportunities for waste. Why? Because individuals measure their productivity based on delivery relative to personal productivity goals.

In the world of the individual practitioner, everyone works at different rates. A developer finishes unit of work ‘A’, hands ‘A’ to a tester, and begins working on unit ‘B’. The tester gets testing ‘A’ and finds a bug. When the tester hands it back to the developer, the developer has to context switch to ‘A’ to revisit the code and remember why the bug occurred to fix it. Working Solo involves lots of context switching – which introduces waste.

Another common source of waste comes from team imbalance. For example, your team has sufficient numbers of developers to build an app, but you haven’t hired enough testers to ensure that the app behaves as expected on all user platforms. If you constrain individuals in their silos, your team may falsely see itself forced to choose tradeoffs that increase the likelihood that you will release untested code.

If your team runs solo and you reward individuals for their personal productivity, you might be surprised at how the team doesn’t meet all the schedules that matter to you.

Pairing

Next, she looks at ‘pairing.’ Engineers work together as pairs. They can be colocated or work remotely, but they work together. In some cases, they share ideas and divide tasks. In the more explicit cases, no member of the team can both come up with ideas and write code. Someone with an idea has to explain it to the other, who actually writes the code. In pairing, the team shares ideas and experience – and learn together from each other.

Pairing helps the overall team write code that incorporates more robust and thoughtful design as two minds work together to deliver pieces. And, two people who work together learn from each other. Successful airing builds trust and team collaboration.

Mobbing

Finally, Lisi looks at ‘mobbing.’ In mobbing, a large group of people comes together to think and create. Mobbing, one person takes the keyboard and acts as the ‘driver’. The rest of the people suggest ideas and must explain to the driver what they mean to build what they are explaining.

A mob with a lot of ideas can seem chaotic – and it can lead to lots of teamwork… if you are deliberate in mobbing and use some thoughtful rules, your mob can be effective. The most important parts:

- Keep everyone engaged – be in a place where you are either contributing or learning from others

- Use the “yes, and…” approach from improvisational theater

- When you have multiple ideas, try both – starting with the person with least experience (remember, it’s about learning)

- In the mob, everyone is learning – be kind and respectful

When To Use Which Approach

Finally, Lisi goes back to the idea that there is no ‘one size fits all’ to collaboration styles. In some cases, teams can see that certain problems can be divided into solo work. In some, they will gravitate to pairs. And, at times, they will call for a mob.

Her point, though, is that teams must know these approaches exist and have experience with all to find which will be the best for the team output in default as well as knowing how to handle the others when necessary.

The key metrics involve team productivity – not just individual productivity. If you track individual productivity without tracking team waste, you don’t know where you are building inefficiencies. And, once you begin to track team productivity, you start to see which approaches work best for you as a development organization.

One hidden productivity benefit of collaboration comes from interdependence. If only one person understands customer needs, or specific test approaches, workflows depend on that person always being part of the loop. While that may seem to give those people special power of knowledge, they also seem personally constrained so they cannot take a vacation or even a sick day without their absence impacting team productivity.

When individuals share their knowledge, two really good things happen. As teams start tracking the flow of work through the team, they see that the expert can take time off without impacting team productivity. And, for the experts, they can continue to develop their knowledge in different areas so they don’t become a siloed specialist whose quest for new knowledge and expertise becomes blocked by solving the same problem all the time.

Whole Team Testing – Conclusions

Before I get started with my other conclusions, I want to mention amazing resources. Lisi includes a generous set of links to both paid and free resources you can use to learn more and share with your team. The course serves as a starting point to what could lead to a major change in the way you work.

As I took the course, I realized that ‘Whole Team” means more than just engineers. Lisi made it clear that everyone in the product delivery cycle plays a role. As team members collaborate and learn, the team can become more productive. To succeed, the team needs a willingness to experiment and tools to measure effectiveness.

Lisi got me to realize that the factory view of waste, which I read about in The Goal, makes sense in a software context as well. Creating software means creating value. The value for the software maker starts with the value that customers obtain – which means building high-value, defect-free experiences for customers as they use the product.

Similarly, I had not thought about experimentation in ways to get faster team delivery, and that group collaboration styles could impact team productivity. I have worked on projects that tracked team velocity. I could easily see adding this approach to teams in the future – and not just in software development.

Lisi’s point wasn’t simply that collaboration matters during coding. I inferred that we should look for opportunities to use pairing or mobbing – even during design, planning, or release. Her point, as I saw it, was that a rigid approach to team structure limits team productivity. By adding collaboration and work style skills to a team, we increase the opportunities for the team to increase team velocity and productivity.

Top comments (2)

We have slowly been fostering a culture that lines up with your article.

Everybody is responsible for testing. Developers write integration tests code. And items are not "done" until they have been verified and validated (code review, functional testing, etc).

It all boils down to "end-to-end" ownership of tasks, instead of "handover" of partially completed artefacts.

Maybe it's the quarantine talking, but I can't help to think that 90% of these frameworks and approaches can just be replaced by fostering a culture where people: