I intend on documenting all that I learn in these early stages of my programming education for 3 reasons:

- If nothing else, to solidify what I learn

- Receive negative feedback from those more experienced

- Help other beginners through what I write and the feedback I receive.

The most important part to me is item 2 - I am a firm believer that negative feedback is one of if not the most important ingredient to intellectual growth. I have never had a programming mentor, and I don't see the possibility for one in the near future, so I want to make up for the lack of that feedback element as much as I can. So I encourage any experienced developer reading this, if you see something inaccurate or inefficient in what I am writing, please feel free to drop some knowledge bombs on me. In this article specifically, I am open to feedback on security best practices, because that seems like a too-often neglected area, and one in which I have a lot to learn.

That being said, I am writing today on lessons learned from making my first web app, which I did using the Sinatra framework. I will touch on what I learned about implementing proper application security, and then on a Decorator Design Pattern which I utilized in the project.

Security

I was really excited to learn about and try to implement an OOP design pattern, but that wasn't the first area of further study I encountered while making the app. Instead, it was the hurdle of instituting proper security. While this perhpas didn't have the elegance that I was hoping for,

it is an essential tool which is extremely practical and needs to be taken as seriously as any new algorithm or efficient design pattern.

Even in a simple web app, proper authentication and authorization are not trivial. If not taken seriously, you risk exposing your users' information, your app's information, and even compromising your server. [2] Furthermore, you don't develop the skills and the muscle memory which you may need later on to secure a more sensitive application.

So, what steps are necessary for a simple Sinatra App? Well, we have to consider how users are authorized and authenticated. We check their username and password at login against the database. Then we persist a session with cookies. These are the two major areas of vulnerability for our use-case. Fortunately, using ActiveRecord abstracts away guarding against SQL injection at login by using prepared statements (using parameterized queries) OWASP's SQL Injection Cheat Sheet. Sinatra also provides us (almost) all of the tools we need to keep our cookies secure if we take the time to properly use it.

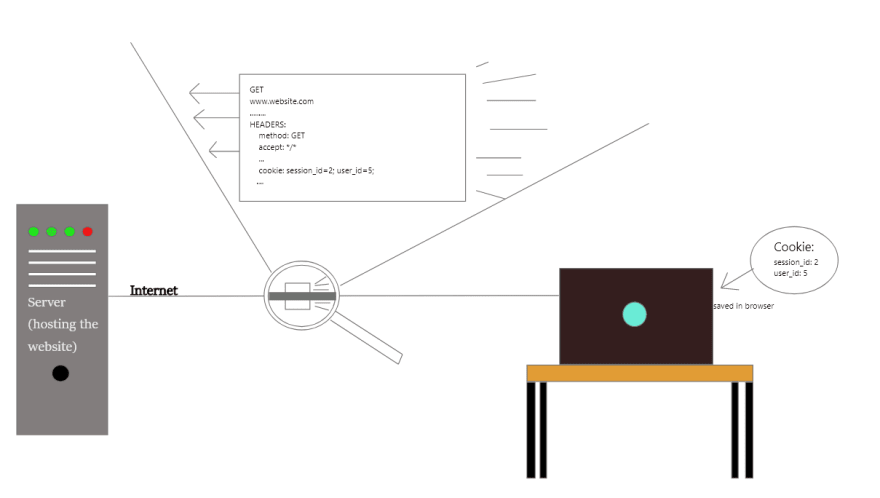

As you may or may not know, cookies are hashes (which are just dictionaries) sent to the user from the server to store on their browser. This is so subsequent HTTP requests from the user to the server can be sent with that cookie, and the server can know information about this user - for example, that they have been previously authenticated (ie, it is used to persist state).

One problem is that cookies which are altered by the user or a third party can cause unexpected, and potentially "bad" things to happen, especially if these changes were done with malicious intent. To help stop "intelligently" transforming cookie data in a specific way to harm the operation of the application, we could encrypt our cookies. That would still potentially allow changing the data, but the person will probably not know how they are changing it. Sinatra does one better by encrypting our cookies by default AND signing them, which encrypts the data AND can tell the server if the data has been tampered with. This is done via the "session_secret".

So, if Sinatra does this, why do we care about doing anything else?

(Note: you can also have your cookies stolen, and then used by a third party pretending they are you even through your own browser - this is something I learned after making the site, and I will discuss it below. Sinatra provides some protection against this by making the cookies HTTP only)

Rack (Sinatra Middleware) signs cookies using HMAC-SHA1 via OpenSSL, using the session_secret and the encoded data in the session. While the HMAC-SHA1 hashing is a one-way process (which means an attacker can't reverse it), it is also a very fast process - which means that an attacker can run it over and over very quickly with different guesses to what your secret word is. They can get your session_secret by running their guess and their cookie data through the same HMAC-SHA1 algorithm and seeing if their output hash equals your cookie hash. If it does, their guess was correct, and now they can fool the server. This is called a dictionary attack. And they don't have to code this process themselves; they can download software made to do this quickly and efficiently. They can also get pre-assembled dictionaries of common passwords and secret phrases. I saw an example where someone cracked a Sinatra app with a session_secret of "super secret" within 45 seconds of a dictionary attack [2]. This is the danger of HMAC-SHA1 being fast - the shorter our string we use, the faster we can get hacked. Sinatra's GitHub page recommends at least a 32-byte session_secret. At one byte per character

"a".bytesize # => 1

we are significantly undershooting that recommendation by using "secret" or "super secret" (which are 6 bytes and 13 bytes respectively).

Also, it should go without saying, that if we make our session_secret available publicly (i.e. put it on GitHub by accident during a commit), no guessing would even have to be done to hack your cookies.

So, what did I do to combat this?

- [X] Obtain a random 64-bit hex that won't be in a dictionary. Generate it via the sysrandom gem which creates the hex using the Native OS's method, which is more secure. Copy the output of the code below to obtain a random 64-byte hex string.

ruby -e "require 'sysrandom/securerandom'; puts SecureRandom.hex(64)"

It should be noted that this is a 64 bit hex value, so each character (even though as a string it is 1 byte) represents 4 bits (or half a byte) per character. (Note that 2^4 = 16, which is the number of possible symbols in a single hex character). So the output as a string is actually 128 bytes (ie there are 128 hex symbols).

- [X] Save my session_secret 64-byte hex string as an environment variable as recommended by The 12 Factor App along with my API Key, so they don't end up anywhere I don't want them to, I can change them easily, and they are language and OS-agnostic. Retrieve it for your app by saying:

set :session_secret, ENV.fetch('SESSION_SECRET')

(Read more about Environment Variables here)

A few days after making the app, I was reading about Cross-Site Request Forgery, (CSRF). I read that people can use posts on sites that do not properly sanitize user input to cause a user to cause a user's browser to visit a site without the user's knowledge (usually via using an img tag with a src to that site). I know very little about Javascript, AJAX, etc, but this prompted me to learn more about it (which I will be sharing soon). Anyway, I decided to go to my site and do some messing around, and I found that I was able to insert scripts into the site via posting comments. This allows an attacker a whole host of options, from stealing other user's cookies, conducting CSRF attacks on them, or writing over that web page. I decided I was going to pretend to be someone trying to sow discontent among the users of the site (I got all of the query information by inspecting the site in the browser, not from the process of making it):

To fix this problem, I needed to sanitize my input. At first I was going to filter it myself, but the best way is probably to use an established method. So I ended up using the sanitize gem, and now my hacking attempts look like this:

I am dissapointed that I got to the point of making a web app and this very basic concept slipped by me. It should be prerequisite knowledge to anyone designing a web app.

My First Design Pattern - The Decorator

My App:

- Let users follow and react to entities with a lot of information being pulled from an API

- Allow users to post and react to posts, as well as react to entities within the app.

Complications:

- My app will be displaying LOTS of data from the API calls - all of which can change rapidly. So, I don't want to save this in my database, because:

- The information would have to be pulled from the API frequently and overwritten in the database frequently - it would be too much redundant work for it to be useful.

- It is too much information for the size of my free cloud database.

- But, I need my database objects for these entities to keep track of what users decide to follow, all posts related to them, likes and dislikes, etc.

Problem To Solve:

- I want to access my database relations and all of my API data in one class for each type of object. For example, I want my Entity class to have all of the ActiveRecord::Base functionality, AND have all of my API data available via method calls. But I want to do this without saving extraneous information.

This problem is solvable in some elementary ways. But Design Patterns aren't always used to transform a problem from being un-solvable to solvable - lots of times they are to make a problem's solution elegant, flexible, and easy for us as developers once it's instantiated.

My Answer The Decorator.

Decorator: Attach additional responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators define a higher-level interface that makes the subsystem easier to use. [1]

Coming to a decision of what design patterns to use seems to me to be just as hard as implementing them, if not harder - here's a graphical representation of how they interrelate, helping us to decide which one to use in relation to others:

That is a lot to take in for my first time. So this is how I came to my decision.

- Design Patterns [1] provides a methodology for choosing a pattern. This methodology includes a list of general problems which you may be trying to solve, and corresponding possible design pattern solutions. Reading this list, I came across Extending functionality by subclassing. I wanted to extend functionality, but I didn't want to subclass. Check.

-

I compiled the listed possible design pattern solutions:

- Bridge

- Chain of Responsibility

- Composite

- Decorator

- Observer

- Strategy

-

I analyzed the intents of each, as described in [1]:

Bridge

Decouple an abstraction from its implementation so that the two can vary independently

This wasn't quite right. Neither the API nor the database model was an abstraction of the other.

Chain of Responsibility

Avoid coupling the sender of a request to its receiver by giving more than one object a chance to handle the request. Chain the receiving objects and pass the request along the chain until an object handles it.

Not applicable.

Composite

Compose objects into tree structures to represent part-whole hierarchies. Composite lets clients treat individual objects and compositions of objects uniformly.

I wasn't working with hierarchical structures. This one wasn't correct for my particular situation.

Observer

Define a one-to-many dependency between objects so that when one object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically

No, because I am not trying to ensure unified actions between connected objects.

Strategy

Define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it

I think I could have solved the problem using a Strategy design pattern. I was unsure which one would work best, and I ended up deciding to go with the decorator.

Decorator

Attach additional responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality.

Sounds about right.

However, I want to add here that my use for a decorator here (even though it worked well for me) is probably not the perfect one. A decorator as a concept is fully utilized when you specifically want dynamic responsibilities allocated (ie they can be given and withdrawn whenever you want) to many individual objects, not whole classes. This prevents this augmentation of functionality affecting other objects. That being said, I do have a plan to refactor to better use the design pattern, and by using it already, it is easier to refactor now.

So first let's do a simple example which explains a 'perfect' scenario for a decorator: imagine I'm buying ice cream. How does a decorator help us?

Set up our Universe:

class PriceError < StandardError

def initialize(msg="That is not a valid price")

super

end

end

class IceCream

def initialize(price: 1.0)

@price = price

end

def price=(amt)

raise PriceError if !amt.is_a?(Float) && !amt.is_a?(Integer)

@price = amt

end

def price

return @price

end

def ingredients

"Ice Cream"

end

end

Now, we want to be able to choose the ice cream we want and change ingredients and price accordingly. To do this, we can create Decorator classes.

class WithJimmies

def initialize(item)

@item = item

end

def price

@item.price + 0.5

end

def ingredients

@item.ingredients + ", Jimmies"

end

end

class WithChocolateSyrup

def initialize(item)

@item = item

end

def price

@item.price + 0.2

end

def ingredients

@item.ingredients + ", Chocolate Syrup"

end

end

class WithOreos

def initialize(item)

@item = item

end

def price

@item.price + 1.0

end

def ingredients

@item.ingredients + ", Oreos"

end

end

So now we can make our ice cream!

my_snack = IceCream.new

my_snack = WithJimmies.new(my_snack)

my_snack = WithOreos.new(my_snack)

my_snack.ingredients # => "Ice Cream, Jimmies, Oreos"

my_snack.price # => 2.5

my_friends_snack = IceCream.new

my_friends_snack = WithChocolateSyrup.new(my_friends_snack)

my_friends_snack.ingredients # => "Ice Cream, Chocolate Syrup"

my_friends_snack.price # => 1.2

There's the functionality we want. I start out with just an IceCream class which is a dollar. That's all I want the class to do. I can check out with just an ice cream, without specifying I don't want the other stuff. I can manually change or 'decorate' my ice cream without the original class having to do anything except for it to adhere to the interface of having price and ingredients attributes. My friend can do the same thing with the same class, but choose different options, getting his own personalized outcome.

I can even add other classes into the mix which can be decorated by the same decorators, provided they adhere to the 'interface' requiring them to have a price and ingredients. Other than that, they can be completely different!

class FroYo

def initialize(price: 1.5)

@price = price

end

def price

return @price

end

def price_to_s

return "$#{'%.2f' % @price}"

end

def ingredients

"Froyo"

end

end

Now just replace the first line in the last example with my_snack = FroYo.new, and you can have the same output except with froyo instead of ice cream!

"So why can't you just program that functionality in as methods into a superclass and then subclass out the functionality?" Well, you can. But a big goal of the implementation of design patterns in OOP design is to favor object composition over class inheritance Why?

- Object composition is also called black-box reuse. It is where we use a bunch of different types of objects to accomplish larger tasks through the way in which they are related to each other at runtime. It's a more modular and flexible way to do things.

- Inheritance can arguably be said to "break encapsulation" - changes to the parent class can (unexpectedly) alter the way the child behaves due to unnecessary overlap.

- It is easier to re-use compositional patterns than inheritance patterns.

- [1] states: "Ideally, you shouldn't have to create new components to achieve reuse. You should be able to get all the functionality you need just by assembling existing components through object composition." It goes on to admit that this is not always feasible, however.

- All that being said, inheritance is easy to use and supported by the language, so there is a benefit to using it at times.

While both ways can solve a problem, object composition helps to prevent large, unwieldy superclasses, allows easier dynamic appropriation of responsibilities, and helps us adhere to the single responsibility principle

Now that we have an intuition of what a decorator is, I think it is important to see a formal definition, in the form of a Class Diagram

So, how did I use a decorator?

I wanted a lightweight database, so I only wanted to save an entity's string identifier in the database, which is enough to get all of the information from the API. Furthermore, I didn't want to save EVERY entity identifier in the database, only ones that users were interested in and interacting with. So, I built a decorator, which took as an initialize argument a class with the API's unique identifier as an attribute. This class needed in the Decorator's initialize method could be one of two things: a "Placeholder" class (which I made), or an ActiveRecord instance (both of which were required to have the entity_identifier attribute). The ability to use a Placeholder or an ActiveRecord class was the main reason I chose using a Decorator over a Strategy, because it allowed me to only save into the database entities users were actually interacting with (ie have an interface which allowed me to use an ActiveRecord class an a "throwaway" class). I gave the decorator the ability to retrieve its relationships (if it was an ActiveRecord::Base instance) by mirroring the ActiveRecord methods. For example, I still wanted entity.user_likes to return ActiveRecord user instances. I wanted to be able to create new database relationships and to call .save on the decorator class as if it were an ActiveRecord object. I also wanted any user interaction to cause the entity to be saved into the database if it had not yet been saved while simultaneously replacing the Placeholder object with an actual ActiveRecord object in the Decorator so I could save and retrieve all relationships. So I included methods in the decorator to do this. Some examples:

def entity_identifier

self.entity.entity_identifier

end

def save

saved = self.entity.save

# note: the EntityPlaceholder #save method returns an ActiveRecord object

self.entity = saved if self.entity.is_a?(EntityPlaceholder)

!!saved

end

def following_users

self.save if self.entity.is_a?(EntityPlaceholder)

self.entity.following_users

end

I also gave the decorator the ability to retrieve information from the API via an APIManager class. The decorator would populate itself with that extra data upon instantiation.

This pattern will let me extend functionality of my app when I have reprisentations of entities in different parts of my app where I will want to display different attributes, get its information from different API endpoints, and interact with the user differently. Any new functionality I want changed / added can be done so on an ActiveRecord object or a Placeholder object via different decorators.

While maybe not the best use-case for a decorator, or I may have implemented it sloppily, or there may be some design pattern that may have worked better, using this pattern certainly made my code easy to work with, gave me practice searching through and choosing design patterns, and awarded me a better understanding of the decorator design pattern. Next time I have a problem, I will be able to have a new way to potentially tackle it, and I will be able to improve on my concrete implementation of the idea.

References

[1] "Design Patterns Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software", Gamma, Helm, Johnson, Vlissides, 1995

[2] One Line of Code that Compromises Your Server

[3] Sinatra GitHub README

[4] SysRandom GitHub README

[5] A Rubyist's Guide to Environment Variables

Top comments (0)