After a few years working as a Software Engineer, I received an invitation to work as an SRE and closer to my company's CI/CD processes. I think the beginning would be ideal to understand the main concepts and patterns. I believe patterns are ways to solve problems and ensure a robust solution for our service, product, platform or APIs. Today I intend to talk about deployments, but from the perspective of the Continuous Delivery process and talk about the main patterns of this technique.

What is Continuous Delivery?

Continuous Delivery is the ability to get changes of all types including new features, configuration changes, bug fixes and experiments—into production, or into the hands of users, safely and quickly in a sustainable way.

Our goal is to make deployments—whether of a large-scale distributed system, a complex production environment, an embedded system, or an app—predictable, routine affairs that can be performed on demand.

Continuous Delivery improve some features in lifecyle:

Low risk releases. The primary goal of continuous delivery is to make software deployments painless, low-risk events that can be performed at any time, on demand.

Faster time to market. It’s not uncommon for the integration and test/fix phase of the traditional phased software delivery lifecycle to consume weeks or even months.

Higher quality. When developers have automated tools that discover regressions within minutes, teams are freed to focus their effort on user research and higher level testing activities such as exploratory testing, usability testing, and performance and security testing.

Lower costs. Any successful software product or service will evolve significantly over the course of its lifetime.

Better products. Continuous delivery makes it economic to work in small batches. This means we can get feedback from users throughout the delivery lifecycle based on working software.

The Deployment Pipeline

The key pattern introduced in continuous delivery is the deployment pipeline. This pattern emerged from several ThoughtWorks projects where we were struggling with complex, fragile, painful manual processes for preparing testing and production environments and deploying builds to them. We’d already worked to automate a significant amount of the regression and acceptance testing, but it was taking weeks to get builds to integrated environments for full regression testing, and our first deployment to production took an entire weekend.

We wanted to industrialize the process of taking changes from version control to production. Our goal was to make deployment to any environment a fully automated, scripted process that could be performed on demand in minutes (on the original project we got it down to less than an hour, which was a big deal for an enterprise system in 2005). We wanted to be able to configure testing and production environments purely from configuration files stored in version control. The apparatus we used to perform these tasks (usually in the form of a bunch of scripts in bash or ruby) became known as deployment pipelines, which Dan North, Chris Read and I wrote up in a paper presented at the Agile 2006 conference.

In the deployment pipeline pattern, every change in version control triggers a process (usually in a CI server) which creates deployable packages and runs automated unit tests and other validations such as static code analysis. This first step is optimized so that it takes only a few minutes to run. If this initial commit stage fails, the problem must be fixed immediately—nobody should check in more work on a broken commit stage. Every passing commit stage triggers the next step in the pipeline, which might consist of a more comprehensive set of automated tests. Versions of the software that pass all the automated tests can then be deployed on demand to further stages such as exploratory testing, performance testing, staging, and production, as shown below.

What is Deployment?

Deployment in software and web development means pushing changes or updates from one deployment environment to another. When setting up a website you will always have your live website, which is called the live environment or production environment.

Deployment Patterns

Deployment patterns are techniques used to introduce new features or updates to an application in a controlled and organized manner. The goal is to minimize downtime, ensure that the new features are stable and perform well, and sometimes allow for testing with a small group of users before making the update available to everyone.

There are some deployment patterns and in this text we will mention the positive and negative points of each one, I will only mention the ones I had contact with either as a Software Engineer or as an SRE: Canary, Blue and Green, Dark Launching and A/B Testing.

Canary Release

A canary deployment is a method that exposes a new feature to an early sub-segment of users. The goal is to test new functionality on a subset of customers before releasing it to the entire user base.

You can choose randomly or a specific group of users and roll back if anything breaks. If everything works as intended, you can gradually add more users while monitoring logs, errors, and software health.

Why we used

Service Evaluation: You can evaluate multiple service versions side by side using canary deployments in real-world environments with actual users and use cases.

Cost effective: Because two production environments are not required, it is less expensive than a blue-green deployment.

Testing: Canary deployment can be used for A/B testing as it offers two alternatives to the users and selects one with better reception.In-built Capacity Test: Normally, it is difficult to test the capacity of a large production environment. Canary deployments offer in-built capacity tests.

Feedback: With the release being made for targeted or a sample number of users, you receive invaluable input from real users and modify canary versions for improvements.

No cold-starts: Unlike new systems that take a while to start, Canary deployments build up momentum to prevent slowness of cold-start.

Zero downtime: Just like blue-green deployments, a canary deployment does not cause downtime.

Simple Rollback Mechanism: You can always easily roll back to the previous version.

Why we not used

Script Testing: Canary release scripting is challenging, since human verification and testing can take a significant amount of time, and the monitoring and instrumentation that is required for production testing may call for further research.

Complexity: Canary deployments share the same complexities as blue-green deployments like many production machines, user migrations, and system monitoring

Time: It takes time to set up a healthy canary deployment pipeline. However, once done right, you can do more frequent and safer deployments.

Deployment at an enterprise scale: An enterprise Canary deployment is difficult to accomplish in an environment where the software is loaded on personal devices. Setting up an auto-update environment for end users may be one method to get around this.

Blue/Green Deployment

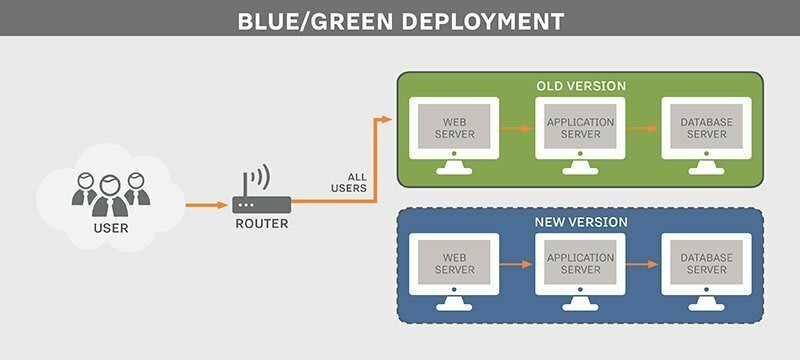

Blue green deployment is an application release model that gradually transfers user traffic from a previous version of an app or microservice to a nearly identical new release—both of which are running in production.

The old version can be called the blue environment while the new version can be known as the green environment. Once production traffic is fully transferred from blue to green, blue can standby in case of rollback or pulled from production and updated to become the template upon which the next update is made.

There are downsides to this continuous deployment model. Not all environments have the same uptime requirements or the resources to properly perform CI/CD processes like blue green. But many apps evolve to support such continuous delivery as the enterprises supporting them digitally transform.

Why we used

Rapid releasing: You can release software practically any time. You don't need to schedule a weekend or off-hours release because, in most cases, all that is necessary to go live is a routing change. Because there is no associated downtime, these deployments have no negative impact on users.

Simple rollbacks: The reverse process is equally fast. Because blue-green deployments utilize two parallel production environments, you can quickly flip back to the stable one should any issues arise in your live environment. This reduces the risks inherent in experimenting in production.

Built-in disaster recovery: Because blue-green deployments use two production environments, they implicitly offer disaster recovery for your business systems. A dual production environment is its own hot backup.

Load balancing: Blue-green parallel production environments also make load balancing easy. When the two environments are functionally identical, you can use a load balancer or feature toggle in your software to route traffic to different environments as needed.

Why we not used

- Resource-intensive: As is evident by now, to perform a blue-green deployment, you will need to resource and maintain two production environments. The costs of this, in money and sysadmin time, might be too high for some organizations. For others, they may only be able to commit such resources for their highest value products. If that is the case, does the DevOps team release software in a CI/CD model for some products but not others? That may not be sustainable.

Dark Launching

A dark launch or dark release is a term that refers to releasing your features to a subset of users to gather their feedback and improve your new features accordingly. Hence, it is a way to deploy a feature but limit access to it to obtain useful feedback.

You can think of it as a safe way to release your features to a small set of users to test whether they like this new feature.

Based on the feedback received from these users, you would either release this feature to the rest of your users or you work on optimizing and improving the feature before doing a full release.

Feature toggles — also known as feature flags — allow you to further decouple the deployment of different software versions from the release of features to users. You can deploy new versions of an application as often as needed, with certain features disabled: releasing a feature to users is simply a matter of toggling it “on.”

Here one implementations of feature flag

Why we used

More experimentation: Dark launches are a great way to gauge customers’ interest in a new feature you’re planning to release. It gives product teams in particular a way to test out their ideas with less risk as only a select number of users are seeing the feature. Teams can choose to run experiments for both front- and back-end features and then release the winning variation to everyone else.

Higher quality releases and faster time to market: uch a technique allows you to put forward high-quality releases as you are updating your features according to feedback from your most relevant users. It allows developers to see how users respond to and interact with the new features to determine whether any improvements will need to be made. Thus, a dark launch is a way to test your new feature in a production environment with real world users. This way, you’ll be able to gather essential metrics to analyze feature performance and to closely monitor how your users engage with the feature.

Why we not used

Microservices are behind feature toggles, which can lead to increased costs and time for debugging microservices.

Additionally, to enable continuous development, teams must be able to move microservices behind feature toggles during development itself.

A/B Testing

A/B Testing, also known as Split Testing or Bucket Testing, compares two variants of the same webpage or app and finds out which one will give better results. It is an experiment where two or more versions of the page are shown to the user randomly. Using statistical methods, which one will be better for a particular goal is determined. This eliminates guesswork and allows data-driven decisions, which results in more conversions and sales.

In the A/B test, a web page or an app screen is taken and modified to create another version of the same. The change can be as small as a button change or a complete revamp. Half of the site traffic is shown in the page’s original version(known as control), and the other half is shown the modified version(known as a variation) of the page. Data is collected with each engagement and analyzed with statistical software. It can be determined whether the change had a positive, negative or neutral effect.

Why we used

Get clear evidence: It’s easy to see how many users complete a transaction with site A over site B. The evidence is based on real behaviour, so is hard data of the type that money men love (and can be presented in a simple-looking, hard hitting chart).

Test new ideas: If you have an innovative idea for an existing site, A/B testing provides hard proof as to whether it works or not. However, you will need to implement that big idea in hard code before you can test it this way.

Optimise one step at a time: If you run a large site, or many sites, then A/B testing is a fantastic opportunity to “patch” test, by starting out in a small corner and then working up to the main pages of the site.

Why we not used

Can take lots of time and resources: A/B testing can take a lot longer to set up than other forms of testing. Setting up the A/B system can be a resource and time hog, although third-party services can help. Depending on the company size, there may be endless meetings about which variables to include in the tests.

Only works for specific goals: This kind of testing is ideal if you want to solve one dilemma, which product page gives me the best results? But, if your goals are less easy to measure pure A/B testing won’t provide those answers.

Could end up with constant testing: Once the test is over, that is it. The data is useless for anything else. Further A/B tests will have to start from a new baseline and other types of testing will only likely be applied to the more successful site, when they could have found equally useful information from the rejected version.

Top comments (0)