Written by Ebenezer Don✏️

JavaScript, originally tailored for making user interactions possible on websites and adding browser effects like animations, has become one of the most important and widely used programming languages today.

As the world’s reliance on the web grew, however, JavaScript was forced to do more than basic browser effects, and so far, the language has done a fair job of meeting expectations. Undoubtedly, the language would have been better suited to meet these new demands had that level of responsibility been understood from the outset.

The need for Scala on the web

You might not question JavaScript’s competence until you start using it to build large, complex web applications. Dynamic typing, initially intended to be an advantage for JavaScript, has become one of its huge disadvantages in modern web development.

Leaving type inference to the interpreter during runtime can lead to a lot of bugs caused by incorrect assumptions. This introduces a lot of apprehension during development since devs may not be sure whether they’ve done everything right when it comes to variable declarations, value assignments, or proper use of data types.

This is where Scala.js shines. Its strong typing system in will prevent you from making these mistakes during compilation, and when you install the Scala plugin in VS Code or IntelliJ IDEA, your IDE is able to point them out before you even compile your code. Having this type of assistance during development makes it easy to write and refactor your code with less fear.

You can use Scala for frontend development, but you’re no longer forced to work with Node.js for the backend because you want to maintain shared code between your server and your frontend. Now you can write both your backend and frontend code in Scala and leverage all Scala’s advantages as a programming language, as well as JVM libraries and even npm tools for web development.

Let’s learn Scala.js by building a web-based countdown timer. Our final app will look like this:

Scala.js setup

To set up Scala.js, we’ll need to install sbt, our Scala build tool and compiler. To get sbt working, we’ll also need to install the Java Development Kit (JDK).

Next, we’ll confirm that we have Node.js installed by running the following code on our terminal:

node -v

This should return the Node.js version currently installed on your machine. Here’s the download link if you get an error instead.

After we’ve successfully set up sbt, we’ll go ahead and create a new directory for our app. Next we’ll create a folder named project inside our application’s root directory, then create a file for our plugins inside the project folder: ./project/plugins.sbt.

Let’s paste the following line in our plugins.sbt file. This will add the sbt plugin to our project:

addSbtPlugin("org.scala-js" % "sbt-scalajs" % "1.1.0")

It’s important to note that our sbt compiler will be looking for a ./project/plugins.sbt file. Also remember that project does not refer to our root directly; rather, it’s a folder inside our root directory.

Managing dependencies in Scala.js

Next, in our root directory, we’ll create a build.sbt file. This is like the package.json file if you’re coming from a Node/JavaScript background. Here, we’ll house our app description and project dependencies:

name := "Scala.js test-app"

scalaVersion := "2.13.1"

enablePlugins(ScalaJSPlugin)

The name and scalaVersion we’ve defined here are important because these will determine the file name/path that sbt will use when compiling our Scala code to JavaScript. From what we’ve defined here, our JavaScript code will be generated in ./target/scala-2.13/scala-js-test-app-fastopt.js. We’ll address the fastopt suffix in a second.

We’ve also enabled the ScalaJSPlugin that we initially added in our ./project/plugins.sbt file.

Working with HTML files

Now that we know what our JavaScript file path will look like when compiled, we can go ahead and create our index.html file and reference our JS file as a <script />. Let’s create the index.html file in our root directory and paste the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Scala JS App</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="./assets/index.css">

</head>

<body>

<div id="root"></div>

<script type="text/javascript" src="./target/scala-2.13/scala-js-test-app-fastopt.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Notice that we also linked a stylesheet file in ./assets/index.css. We’ll create this file after we’re done building our timer app with Scala.

Working with Scala files

Next, we’ll create an index.scala file in the directory ./src/main/scala. This directory is where sbt will go to when looking for our Scala code to compile.

In our index.scala file, let’s define a function, main. This is where we want to house our code. In Scala, Values, functions and variables need to be wrapped in a class. Since we only need this class to be instantiated once, we’ll use the object keyword to create a singleton instead:

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

println("Hey there!")

}

}

In the above block, we defined a Main object and then a main method inside it. The def keyword is used to define functions in Scala and println() will work like console.log() when compiled to JavaScript.

Let’s run our sbt build tool using the following code on our terminal:

$ sbt

If sbt starts successfully, you should get a message similar to this:

[info] sbt server started at local:///.../.sbt/1.0/server/a1b737386b81d864d930/sock

sbt:Scala.js test-app>

Next, to run our index.scala file on our terminal, we’ll use the run command inside the sbt shell. Our compiler will look for a main module with an args parameter of type Array[String]. The return Unit type works just like the void type in TypeScript. Other types you’ll commonly find in Scala are the Int, String, Boolean, Long, Float, and Any types.

sbt:Scala.js test-app> run

Our terminal should show us something similar to this:

[info] Running Main. Hit any key to interrupt.

Hey there

[success] Total time: 6 s, completed Jun 15, 2020, 1:01:28 PM

sbt:Scala.js test-app>

Before we test out our code in the browser, let’s tell sbt to initialize (or call) our main function at the end of our compiled JavaScript code by adding the following line at the end of our ./build.sbt file:

scalaJSUseMainModuleInitializer := true

Compiling and optimizing JavaScript with Scala.js

Next, we’ll run fastOptJS in our sbt shell to recompile our JavaScript file. We’ll be using the fastOptJS command to compile our code whenever we make changes to our Scala file:

sbt:Scala.js test-app> fastOptJS

We can also use ~fastOptJS instead if we want to automatically recompile whenever we make changes — this works like nodemon for Node.js. If our compilation is successful, we should get a response similar to this:

sbt:Scala.js test-app> ~fastOptJS

[success] Total time: 1 s, completed Jun 15, 2020, 1:39:54 PM

[info] 1. Monitoring source files for scalajs-app/fastOptJS...

[info] Press <enter> to interrupt or '?' for more options.

Now, when we run our index.html file on the browser and open the developer console, we should see our logged message: Hey there!

Note that fastOptJS represents “fast optimize JS.” This is best to use during development because of the compilation speed. For our production environment, we’ll have to use the fully optimized version of our compiled JS.

If you guessed right, instead of running fastOptJS in our sbt shell, we’ll run fullOptJS. This compiles to 5.42KB instead of the 54.25KB we get from fastOpt. We’ll also need to change our script src in the index.html to ./target/scala-2.13/scala-js-test-app-opt.js.

Working with the DOM

Using Scala.js on the browser does not make much sense without the Document Object Model (DOM) unless we want to tell our users to open the developer console whenever they visit our site. To set up Scala.js for browser DOM manipulation, let’s add the scalajs-dom dependency to our ./build.sbt file:

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-js" %%% "scalajs-dom" % "1.0.0"

After adding the dependency, our ./build.sbt file should look like this:

name := "Scala.js test-app"

scalaVersion := "2.13.1"

enablePlugins(ScalaJSPlugin)

scalaJSUseMainModuleInitializer := true

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-js" %%% "scalajs-dom" % "1.0.0"

Just like we would import modules in JavaScript, let’s import the document object in our index.scala file:

import org.scalajs.dom.{ document, window }

Destructuring in Scala.js is also similar to JavaScript. Now, we can access the browser document properties through the document object, and the window properties through the window object.

Let’s test this by displaying our welcome message in the browser page instead of the developer console:

import org.scalajs.dom.{ document, window, raw }

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val title: raw.Element = document.createElement("h1")

title.textContent = "Hey there! Welcome!"

document.body.appendChild(title)

}

}

In the above block, we used val to define a variable title. In Scala, the val keyword is used to define an immutable variable, while the var keyword defines a mutable variable — just like the const and let keywords in JavaScript. We also added the raw property to our dom imports and used its Element property as the type for title.

Now when we compile our code and open ./index.html in our browser, we should see a welcome header with the message, “Hey there! Welcome!”

Using template engines with Scala.js

There’s an even simpler way to work with the DOM in Scala. Let’s see how we can use template engines to write our HTML in Scala and even modularize our code. For this part of the tutorial, we’ll be working with the scalatags template engine to build a countdown application.

We’ll also show how we can break our code into modules by writing the navbar and countdown sections as different packages in their own Scala files.

Let’s start by adding the scalatags dependency to our ./build.sbt file:

libraryDependencies += "com.lihaoyi" %%% "scalatags" % "0.9.1"

Pay attention the version we used here, 0.9.1. Depending on when you follow this tutorial, this version might not be compatible with the latest version of Scala.js. In that case, you’ll need to either use a later version of scalatags or the same version of Scala.js that we’ve used here.

Next, we’ll create the navbar package in the ./src/main/scala folder. Let’s name the file nav.scala. Inside nav.scala, we’ll paste the following code:

package nav

import scalatags.JsDom.all._

object nav {

val default =

div(cls := "nav",

h1(cls := "title", "Intro to Scala JS")

)

}

On line 1, we started by using the package keyword to name our nav module. We’ll need this when we want to import nav in the index.scala file. Also, we’ve imported scalatags. The ._ suffix in the import statement imports the DOM properties inside scalatags.JsDom.all as destructured variables.

In scalatags, every tag is a function. Parent-children relationships are defined as function-arguments, and siblings are separated with a comma inside the function arguments. We also declare attributes as function arguments. Here, we’ve used the cls keyword to define the classes for our div and h1 tags.

Putting our packages into action

Since we’ve already named our module using the package keyword on line 1, there’ll be no need to export the object. We can use it in any of our Scala files by importing nav. Replace the existing code in the index.scala file with the following to see how this is done:

import org.scalajs.dom.document

import scalatags.JsDom.all._

import nav._

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val content =

div(cls:="container",

nav.default,

)

val root = document.getElementById("root")

root.appendChild(content.render)

}

}

In the above code, we imported our nav package on line 3, and then we used the default variable we created in the nav.scala file as the content for our div on line 9. On line 12, we’ve appended the content variable to the div with ID "root" in our index.html file.

While we’re still here, let’s create our style file, index.css, inside a ./assets folder in our root directory. Next, paste the following code inside it:

* {

margin: 0;

}

.container {

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

text-align: center;

margin: unset;

}

.nav {

background: linear-gradient(90deg, #04adad 0%, #00bdff);

color: #fff;

padding: 1.5em;

}

.nav .title {

font-size: 2em;

}

#timer {

font-size: 7em;

margin-top: 20%;

}

Now, when we recompile our code and run the index.html file in our browser, we should see something similar to this:

Next, we’ll work on our countdown timer module. Let’s create a new file, countdown.scala, in the ./src/main/scala folder. We’ll paste the following code inside our new file:

package countdown

import org.scalajs.dom.{ document, window }

object countdown {

def timer(): Unit = {

var time: Int = document.getElementById("timer").innerHTML.toInt

if (time > 0) time -= 1

else {

window.alert("times up!")

time = 60

}

document.getElementById("timer").innerHTML = time.toString;

}

}

As you can see from our code, there are a lot of similarities between JavaScript and Scala. On line 7, we declared the time variable using the var keyword. This references a div with an ID of "timer", which we’ll be creating in a second. Since .innerHTML returns a String, we used the .toInt method to convert the time value to an Integer.

On lines 8–12, we used the if-else conditionals, which are quite similar to those of JavaScript. We want to reduce the time value by 1 if it’s greater than 0 and display an alert box with message, “times up!” when it’s equal to 0. Then we reset the time value to 60.

Bringing it all together

Now that we’ve created our countdown package, we’ll use the setInterval method to run our timer function every 1 second. Let’s use the countdown package in our index.scala file:

import org.scalajs.dom.document

import scalatags.JsDom.all._

import nav._

import countdown._

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val content =

div(cls:="container",

nav.default,

div(id:="timer", 60)

)

val root = document.getElementById("root")

root.appendChild(content.render)

}

}

In the above code, we’ve added the import statement for countdown using import countdown._. With this, we can call the timer function using countdown.timer().

Alternatively, we can import the timer function with import countdown.countdown.timer and just call it directly as timer() in our index.scala file. We’ve also added the div with ID "timer" and have given it a default value of 60.

Next we’ll import the setInterval method from scala.scalajs.js.timers and use it to call the countdown.timer() method:

...

import scala.scalajs.js.timers.setInterval

...

root.appendChild(content.render)

setInterval(1000) {countdown.timer}

Finally, our index.scala file should look like this:

import org.scalajs.dom.document

import scalatags.JsDom.all._

import scala.scalajs.js.timers.setInterval

import nav._

import countdown._

object Main {

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

val content =

div(cls:="container",

nav.default,

div(id:="timer", 60)

)

val root = document.getElementById("root")

root.appendChild(content.render)

setInterval(1000) {countdown.timer}

}

}

Now, when we recompile our code using fastOptJS and run our index.html file in the browser, we should see something similar to this:

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve introduced Scala.js by building a web-based countdown timer. We covered the basics of the Scala programming language, how to work with the DOM, browser APIs, working with template engines like scalatags, and the different options for compiling our Scala code to JavaScript.

Scala.js also has support for frontend frameworks like React, Vue, and Angular. You’ll find the setup quite similar to what we’ve done in this article, and working with them shouldn’t be all that different from what you’re used to in JavaScript.

Compared to type-checking tools like TypeScript, Scala.js might be a little more difficult to set up and get used to if you’re coming from a JavaScript background, but this is because Scala is a whole different language. Once you get past the initial stage of setting up and learning a new programming language, you’ll discover that it has a lot more to offer than just type checking.

Lastly, here’s a link to the GitHub repo for our demo application.

Full visibility into production React apps

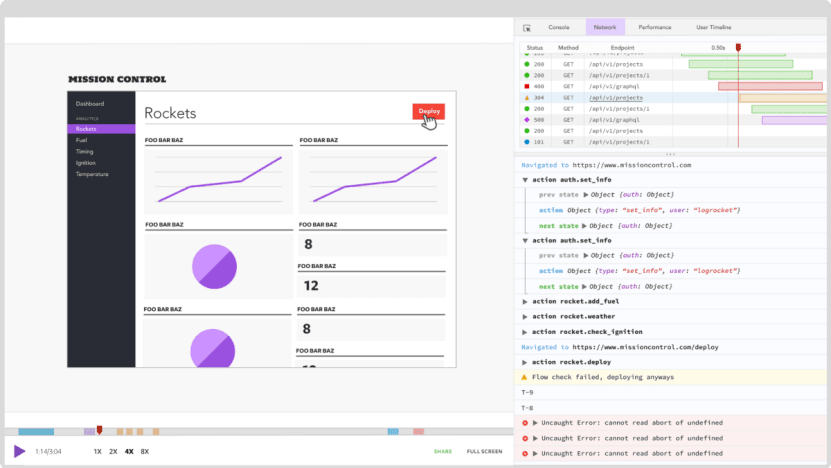

Debugging React applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking Redux state, automatically surfacing JavaScript errors, and tracking slow network requests and component load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket is like a DVR for web apps, recording literally everything that happens on your React app. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on what state your application was in when an issue occurred. LogRocket also monitors your app's performance, reporting with metrics like client CPU load, client memory usage, and more.

The LogRocket Redux middleware package adds an extra layer of visibility into your user sessions. LogRocket logs all actions and state from your Redux stores.

Modernize how you debug your React apps — start monitoring for free.

The post Strongly typed frontend code with Scala.js appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

Top comments (0)