Although rebase is not a complicated concept itself, many people have trouble understanding it.

I believe this is mostly because people new to git postpone or never get to learning the rebase command because they are overwhelmed by all the other stuff necessary to just survive with git. And the fact they keep hearing rebase is a dangerous command makes them keep postponing it's learning.

So if this applies to you too, stay with me to learn how git rebase works on a simple example.

Say you are on your project's master branch (we’ll display only the last 4 commits):

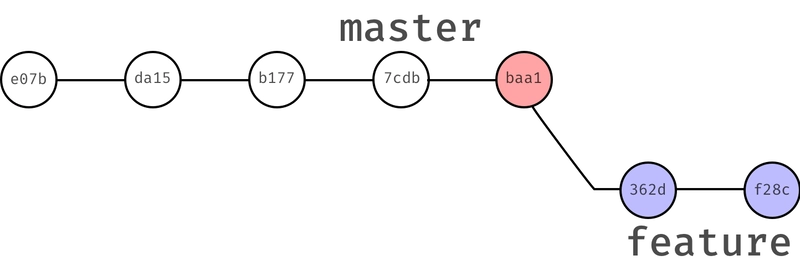

Now you want to develop some cool new feature on a different branch so you create one with git checkout -b feature and make two commits. Now your master and feature branches look like this:

But now someone reports a bug on your application and you quickly switch (checkout) to your master branch to find and fix the bug. After some time you do fix it and push (and deploy) the change. Everything is fine again and you can come back to your feature branch.

But now you realize you have a little problem. Your feature branch still has that same bug that you fixed on the master branch and you realize that the bug will also affect your new code on the feature branch, so you need to incorporate those bug-fixing changes (commit) to your feature branch. But how? Well, there are a few ways to achieve that but the best would be if you could just go back in time like Doc and Marty did, and do the bug-fix commit before you made the feature branch. That way the commit that has the bug fixing code would be contained in the feature branch (once you get back to the future). Well, turns out you can do just that. I mean, not actually go back in time but alter (git) history. And you do it with the rebase command. So, if you are on your feature branch and you do:

git rebase master

This is how your branches are gonna look like afterward:

As you see, the history of the feature branch has changed. If someone would now look at it he/she would think you made (checked out) your feature branch after the bug fixing commit.

So this is great right? Why just not use it all the time? Well, there is a catch. Remember how when Doc and Marty came back to the future it was a bit different? Well, that happens with git rebase too, but don’t worry, your code will stay the same, only the checksums of the commits on your feature branch will change. And what are these checksums? Well, you probably noticed that 40-chars long string that you see right to every commit when you do git log:

commit f5cad47722bc98419fe5037753f5bbe29d3917c4

Author: John Doe <john@doe.com>

Date: Mon Apr 23 11:49:07 2018 +0200

Did some stuff:)

That's the checksum. You can think of checksums as unique identifiers for commits and because of the way git generates them (you can check my blog post on git’s data model for more info) they change on our feature branch after rebase.

So, if the commits had these checksums before rebase:

Then after the rebase, the checksums on the feature branch would change:

And this is why you keep hearing git rebase is a dangerous command. Because it alters history and you should use it with caution.

But why exactly is this dangerous and when? Well, let’s say you are not the only one working on the feature branch, but there are more people pulling and pushing changes to it. And now you do your rebase and (force) push the changes to the feature remote. Now, when your colleague Bob tries to pull from the remote feature, everything explodes because his local version of feature branch has a different history than the remote version.

OK, so Bob’s computer won't actually explode, but there is no nice way for him to fix this situation. So, as a general rule of thumb, if you are working on a public branch (that other people are pulling changes from), you will not do a rebase on that branch. If, on the other hand, you are working on your local branch and haven’t pushed it to the remote server yet, or you did but it is still only you who is working on that branch (you must be sure of that) then you can do a rebase on it.

Top comments (20)

Bob can actually do this to fix it:

git checkout -b feature-bob- creates a new branch from the existing feature branch for Bob, with his changesgit checkout feature- go back to the original branchgit fetch origin- fetch changes from remote after the rebasegit reset --hard origin/feature- resets Bob's currentfeaturebranch to be identical with remote'sgit checkout feature-bob- go back to Bob's branchgit rebase feature- include your changes into his branchBob now keeps working on his feature branch and just rebases on top of yours. That way you can work on the same feature, but still do your own rebase.

From the Bob's local

featurebranch, he can accomplish all this with just:git pull --rebase origin featureI use

pull --rebaseall the time when I don't want a merge commit every time I pull down from the public branch. Simply replays my local commits on top of the remote head.Yeah I was going to mention this in the fetch flow.

It actually makes collaborating with rebase completely acceptable as long as you never merge which I think may work at times too.

Hello Dalibor,

This solution would fit the "no nice way for him to fix this situation" category in my opinion :)

Rebase is a nice trick, but not a real workflow:

Just pull and merge, it's ok. Don't lie to git's history.

Saying that rebase is not a real workflow is relative. It will depend on what level you are rebasing things. Although it might not be the best option when you do not put your work in separate branches and instead commit everything to the default branch, I can say that rebasing makes your git history much cleaner. So a good approach in my opinion is when you work in separate branches and use rebase on those to clean history a little bit and then after that you merge to the default branch, which should give you merge commits, which believe me can be really helpful.

Git push --force-with-lease

That is a slightly safer push, wish the command was shorter.

Using git to communicate, I believe requires rebase.

Git is a Communication tool

Jesse Phillips

It depends on how you work. If your branch is only being worked on by you and/or your team, just communicate before you git push -f it, so everyone will be up to date afterwards. If that doesn't work for you, merge and silently cry about your ugly git history.

Hello Roger,

I wouldn't call rebase a "trick". It's a git command like any other.

Whether you'll use it depends on your(team's) workflow.

If the two commits of the feature branch have conflicts with the new one in

master, I'll have to resolve conflicts twice, which is even worse if there are more. This is what I normally do:This is what I do when working in a feature branch + PR workflow, what do you think?

Hy David,

Yes, this happens because during rebase git re-applies the commits (from feature branch in this case), so if you have conflicts on some commit, you must resolve them before git can try to re-apply the next commit. And if you have conflicts on every commit than you'll have to do it fore every of those commits.

Your workflow helps you avoid that "multiple" conflict resolution but you lose you commits granularity since they all get squashed into a single commit.

Only one thing - checkout interactive rebase, it's a cool feature and could help you combine a message for your squashed commits.

Exactly, but I actually prefer to have a single commit for a feature, while I like to have the whole commit history of my branch while I'm working on it, so yeah, interactive rebase is a good choice for that :)

I need to evaluate more cases, but if each commit conflicts, you don't eliminate any merge conflict by squashing. You'll just get one big collection of conflicts to deal with.

I'll have to admit that I rarely use rebase. I don't mind the "messier" git history, as as far as I am concerned it is a true history.

On top of that, I am of the "commit early, commit often" mindset and hand in hand with that is "push your branch to origin often IN CASE OF FIRE".

And since I instilled this in my team as well, our branches are pushed up public often, which is exactly the scenario one should not be rebasing from.

So it works out for us just fine.

Vim has the true history which is actually really helpful during initial changes. But I don't commit my vim history to git, I have a different goal when I commit.

Git is a Communication tool

Jesse Phillips

Thanks for explaining rebasing! :D

Where we're going, we don't need old commit ids.

But seriously, you combined one of my favorite movies with my favorite git command. Nailed it!

Really well explained!

I don't suggest using rebase because if that red node on master removes some dependencies and functions that you actually need in those purple nodes, your commits won't build.

That is fair I suggest using commit --fixup to get the solution to the right commit. You still need to make a solution on merge.