The famous puzzle of the two lying brothers is a both well known and poorly understood:

There are two doors in front of you, each guarded by one of two brothers. One door leads to freedom, the other to certain doom. One of the brothers can only tell the truth, no matter what question you ask, and the other can only tell lies. You can only ask one yes-or-no question, directed at just one brother, and then you must choose one of the doors. What question do you ask?

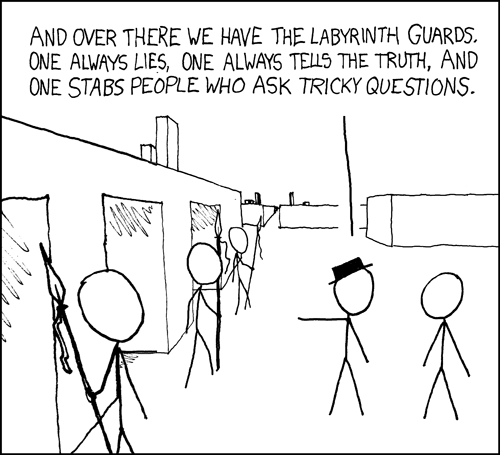

It appears throughout popular culture (including in Labyrinth), but wherever it is found, the characters that encounter it typically react with the same mixture of confusion and half-remembered solutions that people in the real world have in their heads. Most people remember how to answer the puzzle, having been walked through it at some point, probably when they were a child.

They know that you are meant to ask one brother what the other one would say when asked if this door leads to freedom. And it is easy to convince someone that this is the case by walking through the truth table of how that brother would respond, case by case. But it is much less obvious why this is the answer, and how you would come to this solution from first principles.

It turns out that the reasoning here is extremely simple, and lets us use what we know about functions to find the right question (and thus, answer).

What we need to know

The puzzle is really asking us to determine one actual piece of information with the one yes-or-no question. Specifically:

- Is this door the door to freedom?

The question:

- Is this brother lying?

Seems to be essential to finding that out, since while we only care about where the door leads at the end of the day, we cannot determine that until we know if the brother is lying. So the first task is to find out if the brother is a liar.

Interrogation Techniques

We can proceed as per a police investigation, and interrogate the guard.

If we want to find out if we are being lied to, we can ask questions about known facts:

(def facts {:sky-is-blue true

:water-is-wet true

:black-is-white false

:up-is-down false

})

We can then ask about these known facts, and then see if the guard gives the correct answers. Let us say that guards are functions that take in a set of facts, and then answer questions about that set, e.g.:

(defn truth-teller [memory]

(fn [question] (question memory)))

The truth teller is straightforward, just pulling a fact out of memory, and then passing that back to us.

(defn liar [memory]

(fn [question] (not (question memory))))

A liar is exactly the same, except that after recalling a fact, they tell us the opposite of what they know to be true. So trying that out:

(let [a (truth-teller facts)

b (liar facts)]

(doseq [fact (keys facts)

guard [a,b]]

(println (str "Guard is telling the truth? "

(= (facts fact) (guard fact))))))

Since the only difference between the two guards is how they process the contents of their memory, we can refactor this out:

(def lying not)

(def truthfully identity)

(doseq [fact (keys facts)

guard [lying truthfully]

]

(println (str "Guard is telling the truth? "

(str (= (facts fact)

(guard (facts fact)))))))

So determining whether the guard is a liar is equivalent to asking if an unknown function is equal to identity or not, which we can do by looking at their outputs.

We don't care who you are, just tell us the (not) truth

So far we can detect the liar if we have a shared set of facts we can agree on, and then we can just compare outputs. Then we know if we have a not-guard or an identity-guard. But wouldn't it be nice if we could transform a not-guard into an identity-guard? Then we could trust our answers. Well, lets look at the opposite, turning an identity-guard into a not-guard.

If we remember the laws of function composition, identity is the neutral element:

id . a === a

a . id === a

or in the case of not:

id . not === not

not . id === not

This means that if we compose the two guards together, we can get a not-guard every time, and it doesn't matter which order they come in, we are guaranteed to get a not-guard back:

(defn not-guard [[a b]] (comp a b))

Well, what use is a not-guard? Not much when we don't know if they are one, but once we know for sure that is what they are, we can transform them into a truth-teller, since not . not === id. So this means that whether the guards are [liar truth-teller] or [truth-teller liar], we can get a truth-teller by applying these transformations:

(defn tell-the-truth [guards] (comp not (not-guard guards)))

Finding our way out

Happily, this means that given either order of guards, we can always fashion a truth-teller by composing them together, and use this composite guard to solve the puzzle:

(defn solve [guards door-a-leads-to-freedom]

(let [truth-teller (tell-the-truth guards)]

(if (truth-teller door-a-leads-to-freedom)

:door-a

:door-b)))

Which of course if a round-about way of saying:

doorA === (not . not . id) doorA

doorA === (id . id) doorA

doorA === id doorA

doorA === doorA

What does this mean in terms of the puzzle? Composing two functions means to thread an input through two functions, and the two brothers here are pure functions of facts, one being the identity function. Composing two respondents means asking one how the other answers. Whenever we have an identity function and something else, we eliminate the identity, and simplify to whatever that something else is, no matter the order of composition. Then we can proceed on the assumption we are dealing with that. In the case of the guards, that means no matter which is A and which is B, we treat each of them as the liar, and we know how to deal with lies.

In some ways this puzzle is like solving an equation by dividing by a common factor. When we know that one of the factors in 1 we don't even have to do that, since (x * 1) and (1 * x) both equal x, just as (f . id) and (id . f) both equal f. It is almost surprising that we can use such simple equational reasoning to reason about functions in the exact same way we reason about numbers, and is an example of laws are important.

Category Theoretical Post-Script

Some people may even have heard of the description of a Monad as a "Monoid in the Category of Endofunctors", well "A Monoid in the Category of Endofunctors" is amusingly exactly the situation at hand. The functions identity and not are Endofunctors, being functions from Bool -> Bool. And they form a category that composes with (.) and has the identity id, or equivalently, they are are a Monoid where mappend is (.) and mempty is id. So we can use either set of laws, to show that we can factor out the identity element, i.e. the truth-telling guard, leaving us with just the liar.

Latest comments (0)