Refactoring CSS

What to keep in mind when thinking about refactoring your CSS

Photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

As developers, we work in an industry that has a luxury not afforded to many others. We can edit things that have already been published.

In many other industries retroactively changing things is incredibly difficult. A writer can’t take their book off the shelves and rework a sentence. An artist can’t remove layers of paint to improve the layer beneath, and a construction company can’t build a new floor off-site and slot it back in when it’s ready.

Us developers? We can iterate internally on the design, on the frontend or backend, and then continue to push changes once the product is live.

This is a very good thing.

Because, no matter how careful we may be, we’re almost certainly going to come across code that we look at and think, “this could be better.” At which point you and your team might decide it’s time to improve it.

It’s worth noting…

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” — Benjamin Franklin

Even though the idea of a refactor sits over most mature products it doesn’t mean you should code with a we’ll-rewrite-it-later-anyway mindset.

Having a style guide, an outline of the project, a plan for approaching it, a proper directory structure, and naming convention are still important. Having these in place is what stops a quick refactor from becoming a complete overhaul.

“Everyone knows that debugging is twice as hard as writing a program in the first place. So if you’re as clever as you can be when you write it, how will you ever debug it? “— Brian Kernighan, The Elements of Programming Style

Refactoring can be difficult and is often tagged on as kind of an afterthought. The truth is, just like accessibility and responsiveness, it should be planned and approached as part of the main work. Not an extension to the project.

Why would I have to refactor?

A CSS Mess. A CESS, if you will.

As we mentioned at the beginning, we can constantly iterate on the work we do. Because of this, our job continues after pushing to production, and the codebase can grow larger and larger. We can keep the code as clean as possible along the way, but with enough “quick changes”, pulls and merges, things can get messy.

Let’s take the following fictitious example:

A website has a blog section with a nice card layout. The CSS (if using BEM )might look something like this:

/* _blog-post.scss */

.blog-post {}

.blog-post__header {}

.blog-post__title {}

.blog-post__image {}

.blog-post__footer {}

The product changes and you’re asked to add a news section. It has a similar layout and style. You don’t want to give a news-article the same class as a blog post. So you make another file:

/* _news-article.scss */

.news-article {}

.news-article__header {}

.news-article__title {}

.news-article__image {}

.news-article__footer {}

You could be asked for a similar events section, but let’s leave it as it is. Now we have the problem of unnecessary duplicate code. What we probably want is to remove the above files and have something more like:

/* _post.scss */

.post {

&__header {}

&__title {}

&__image {}

&__footer{}

&.post--blog {

/* Modifier stuff here */

}

}

But of course, CSS is finicky and operates globally. When a new developer comes to this CSS they might be scared of changing it for fear of it breaking something elsewhere. On top of that, they might be working to a deadline, or maybe they’ll say “I’ll come back to this later”, but never will.

These little things add up over time and might result in your team deciding on a refactor.

When and when not to refactor

Maybe you’re thinking, why would I even touch this if it works? And that’s a very important and necessary question because you might not need to. The following isn’t an exhaustive list, but just an idea of things that may sway you one way or the other.

When it might be time to refactor

- Your CSS is excessively large.

- Hinders performance in some way (large load time, layout breaks in specific use cases)

- Developers spend time working around the code, not with it.

- You want to increase the readability for newcomers.

- You work in a very large team and refactoring now means you’re saving a little time for a lot of people.

- A specific issue has been raised by multiple people.

- The refactoring will be quick.

When it might not be necessary

- A rewrite or re-design is coming up, and it will be easier to write from scratch.

- The CSS “looks bad”, but no developer has had an issue with it. And no user has reported any

- The CSS is bad but belongs to an element or component that won’t be touched. Take for example a footer which isn’t going to change. If a developer had some initial problems, but it’s finished and works, it might be worth focusing your attention on a different part of the site.

Of course, whether something is worthy of a refactor is your choice. The above are just indicators I’ve learned of. So you decide it’s time, now what?

Refactoring “on the move”

This should be your first port of call. These are small pieces of tidying up that are more relaxed and less arduous than a full-on refactor.

It involves going over your .css or .scss files and combing them for classes that hold the same style declarations or have declarations that override each other. You should add comments to rules that don’t make immediate sense or seem to be unused. For instance, the class might not appear in the HTML but is added later by JavaScript. For example:

.faq {

&.is-expanded {

/* Toggled when user clicks on element */

}

}

Of course, doing this manually might take a while, so use a Linter. You can tweak your config and be warned upfront about things like duplicate declarations or empty selectors.

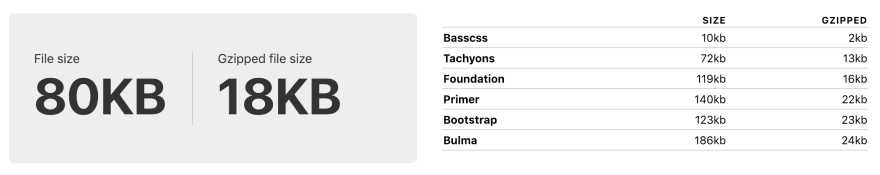

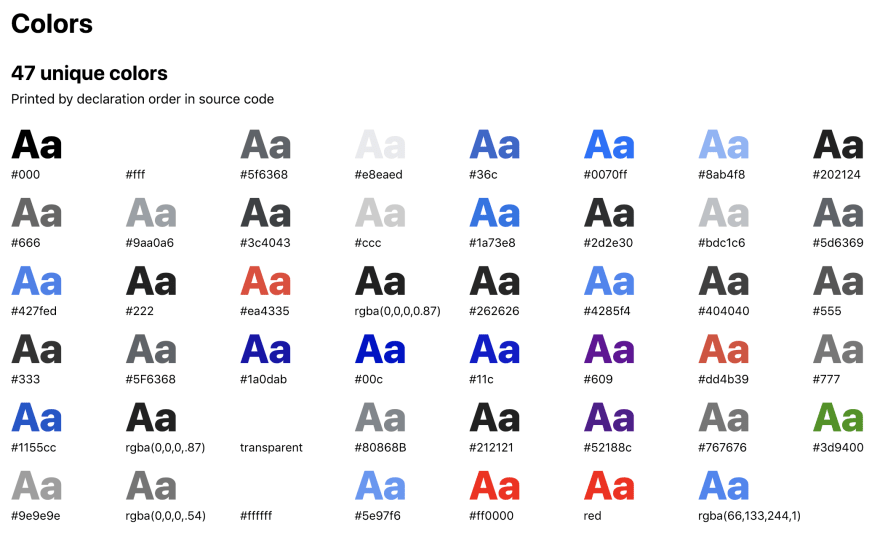

You can also get some valuable information about your CSS using CSS Stats. This site can provide valuable information about the inline and linked CSS you’re using. You can get size comparisons to popular libraries. Declaration counts for layout, spacing etc, it shows a specificity graph… And the number of unique declarations for things like colour or font sizes.

Take the stats with a grain of salt, and have a general idea of the codebase you’re working on. Because having 40 unique colour declarations might seem like a lot for a standard marketing site, but for online clothes stores with colour swatches these results wouldn’t be so surprising.

When used properly the stats can be very insightful and can be used to weed out unnecessary rules. If your design system lists 7 different sizes in its type scale and you have 30+, maybe it’s time to refactor those declarations into a single class or remove the declarations that are never actually applied.

The “component refactor”

This is the refactor that is done with one specific element or component in mind. For example, you’ve decided to tackle the header because multiple devs have had problems adding to it or modifying it.

The thought of diving straight in and making everything better for a lot of people can be motivating. But slow down and ask yourself or amongst your team the following questions:

What really needs to be refactored?

Let’s imagine we have a large messy footer that has some unused CSS and a bunch of hacks.

It might seem like an ideal candidate, but if it’s a part of the site that works, no users have reported a problem and it isn’t due to be updated for a while it can most likely be pushed to the back of the queue.

Maybe you have a nav that has many different variations or states might be better as a target. Maybe it’s snowballing and developers keep adding more classes with more specific rules to override it’s already specific selectors. Or perhaps we know that the client wants to add more states in a coming update. Or, you’ve finally dropped support for an older browser and you can use newer features like flexbox and rewrite the hacky float filled CSS from before.

Is the refactor short enough?

A refactor of a whole page might take longer than you think. You might be well served to set a smaller goal. Rather than tackling a whole page, how about just the buttons, or forms? Having smaller targets means you can demo the improvement more quickly, and be back on other projects/dev work faster than if you were tackling something huge like the home page. You should always have the end goal in sight. Refactor, move on, repeat.

Where shall I do my “refactoring”?

Basically, anywhere but the project it came from. CodePen, jsFiddle, a playground HTML file in your dev environment.

The main point is that it should be built away from your old stale codebase, though could import the grid if absolutely necessary. Refactoring in this way means that we rework our component away from all the conflicts or overwrites that were causing it to be messy in the first place. We can build it and test it in a new sterile environment, knowing that when it’s complete and reincorporated into the site we can identify more easily where the conflicts come in.

How should I implement the refactored code?

In Isolation 👀

Once this is done, you can swap out your old nav for the new one. At this point, there will likely be some conflicts with the old CSS. So what do we do?

We need need to write some hacky CSS now to help preserve our sanity later. This sounds counterproductive, but it’s actually a good strategy when refactoring. We can isolate, signpost and write this “quick fix” CSS until our refactored component looks as it should, then as the old CSS is removed and these conflicts disappear we can remove these hacks. Let’s look at a practical example with a nav.

- Step 1: We’ve refactored the nav in isolation. It follows all best practices and is ready to replace the old clunky one. We swap out the HTML and import our new .scss file.

- Step 2: We’ve brought it in, but it doesn’t look right. The styling for the colour and font size are off because of the specificity of some older badly written code.

Code below:

/* _links.scss (old) */

header > nav li a {

color: blue;

display: inline-block;

padding: 0 0 0 10px;

font-size: 12px;

}

/* _new-nav.scss (new) */

.nav__link {

padding-left: 10px;

color: red;

font-size: 14px;

}

- Step 3: We code to fix the problem, but we do so away from our clean CSS. In a well-commented, appropriately named file reserved solely for “bad” code (fixes.scss, hacks.scss, shame.scss or temporary.scss would all work).

Code below:

/* _fixes.scss *//*

Add !important declarations to the .nav__link class because more specific code from _links.scss is overwriting the colour and font-size.

*/

.nav__link {

color: red !important;

font-size: 14px !important;

}

- Step 4: Now we “attack” the bad CSS. We go in and remove the old stale CSS that was conflicting with our shiny new nav.

- Step 5: Now we can remove our fixes CSS for that specific conflict.

- Step 6: Repeat until old CSS and hacky CSS are removed.

- Step 7: Marvel at the beauty you have created.

Harry Roberts explains this approach thoroughly in his talk from the WeAreDeveloper’s Conference in 2017. https://youtu.be/fvTryZjGyg8

Conclusion

The need for a refactor can be kept at bay by improving as you are going along and introducing useful build tools like linters, or products like CSS stats into your workflow. But when and if a refactor is necessary, it should be approached methodically and as carefully planned out and iterated on as the actual product itself. Hopefully, the information above can help you better prepare.

Feel differently? Have anything to add, agree, disagree? If you’ve got any feedback we’d love to hear from you — please leave a comment here, or drop us a line on Twitter. We’re @InktrapDesign.

Top comments (0)