OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect are becoming the de-facto standard for handling authentication and authorization in modern applications.

This post is the starting point of a series of posts covering OAuth 2.0 and OpenID Connect (OIDC). It introduces you to OAuth and OIDC and tells you why you'll want to leverage these mechanisms when dealing with authentication and authorization. We'll also take a look at OAuth tokens and the most widely used OAuth extensions.

Beware that I use the terms OAuth and OAuth 2.0 interchangeably. So when I say OAuth I mean OAuth 2.0 not the 1.0 version.

What Is OAuth?

Before defining what OAuth is I'd like to make a clear distinction between Authentication(AuthN) and Authorization(AuthZ): AuthN defines who you are. On the other hand, AuthZ specifies what you can do.

To save you the time from looking up to Wikipedia here is the definition:

OAuth is an open standard for access delegation, commonly used as a way for Internet users to grant websites or applications access to their information on other websites but without giving them the passwords

Keep in mind that OAuth 2.0 is an authorization framework. Like most frameworks, it does left many things undefined and it's up to the specific OAuth implementation to define the missing parts.

Here I am describing some of the most widely used oAuth 2.0 extensions:

JWT

JSON Web Token, short for JWT defined by RFC 7519 as a way to repensent claims to be exchanged between two parties. Note that OAuth doesn't require JWTs, but it's common to use it along with it. JWTs are encoded, there're not encrypted; so make sure to not put sensitive information into JWT. It's not secure! If you want to share sensitive data you could leverage an opaque token or JSON Web Encryption (JWE).

A JWT contains fields like:

- iss (issuer): Specifies issuing auth server

- iat (issued at): Issued at time

- sub (subject): Identifies the principal that is the subject of the JWT(the user)

- aud (audience): Represents who should use it

- exp (expiration): Specifies the expiration date

Token revocation

The token revocation spec defined by RFC 7009 as a way to revoke(cancel) a token via API. Note that implementing this spec is optional, and it shouldn't be because if your tokens were leaked to malicious actors, you'd need a way to make the access token invalid without needing to wait for the expiration date of the token.

Token introspect

The token introspection spec RFC 7662 examines a token to describe its contents, this is useful if you want to know the content of an opaque token. Also, it is used to determine the validity of a token. Finally, With introspection your client applications can query the authorization server to know if the token is revoked.

Dynamic Client Registration

The Dynamic Client Registraction spec RFC 7591 let systems to register themselves with the auth server for reqesting tokens and It is done programmatically. Once registered you could leverage Dynamic Client Management spec RFC 7592 to manage and maintain registered oAuth clients.

Authorization Server Metadata Discovery

All the above specifications are optional. Not to mention that not all auth servers will support all the above oAuth 2.0 extensions. This is where Authorization Server Metadata Discovery spec REF 8414 known as oAuth Discovery Document comes in handy. It allows us to query the auth server to learn about its capabilities. Also, the server will tell us what endpoints are available.

Why OAuth?

OAuth was created to solve authentication issues. Previously, third-party apps using HTTP Basic users were prompted for username/password so the app can make authorized requests on their behalf. So you have to trust the app because if you give your email/password to a third-party app, it will store your credentials in their datastore. Using HTTP Basic decentralizes password management to third-party apps. Many of these apps will have to store your credentials in their datastores; therefore, third-party apps will be required to do their best to secure their datastores, which isn't an easy thing to do. Security leaks in those third-party apps could emerge, and boom! Users are doomed!

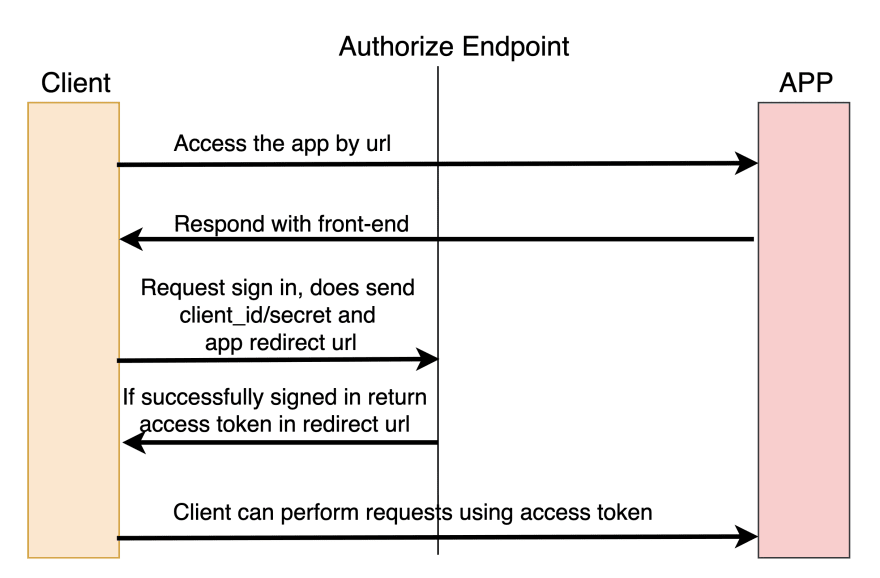

With OAuth, instead of sending username/password to the API every time you make a request, you'll register your application to the OAuth server and then send a client_id(provided by the OAuth server) and a secret to getting a signed access token which will authorize future requests. The diagram bellow illustrates the basic process for getting an access token:

OAuth Tokens

RFC 6749 defines an OAuth access token as:

Access tokens are credentials used to access protected resources. An access token is a string representing an authorization issued to the client. The string is usually opaque to the client. Tokens represent specific scopes and durations of access, granted by the resource owner, and enforced by the resource server and authorization server.

I found this to be a vague definition, so let's try to demystify it.

As we've learned previously, OAuth 2.0 is a framework or a loose agreement that leaves many things undefined. The tokens are among the many things. Note that it gets pretty clean when working with an OAuth implementation. Typically an Opaque or JSON Web Tokens are the most common approaches to OAuth:

- An opaque token is a unique string that acts as a database key to retrieve relevant information, only the issuer(auth server) knows the format; there's nothing to decode or decrypt in this token.

- JWT has readable content. If you go to https://jwt.io/, anyone can validate and decode the content of that JWT.

Validating a JWT

Validating the JWT is a crucial step in establishing trust between the auth server and the app. If we validate a token correctly, we can trust it.

These are typically the steps to validate an access or ID token:

- You have to retrieve your signing keys. Often, these keys are available in the keys document via URL from your auth server.

- The JWT contains three components: the header, payload, and signature separated by a dot. Decode these components using Base64

- After decoding the JWT header, grab the kid(Key ID) claim, which should be precise as the key from the original document you retrieved a couple of steps ago. If they don't match either the document is out of date, or the token is not for you, and you should decline it immediately.

- Next, use the referenced key to sign the payload and compare it against the original signature. If they don't match, then the token is not for you, and you should decline it immediately.

- After knowing that the token is for us and untouched, we'll examine four claims from the payload. First, the ISS(issuer) claim should match our auth server, so we know where it originated from. Next, the AUD(Audience) claim should match the values set in our auth server, so we know who the token is intended for. Next, CID(Client ID) claim should match the Client ID of our app that requested the token. And finally, EXP(Expiration Time) should be in the future; If our EXP is in the past, it means that the token is no longer valid, and we can't trust it.

If our token failed in any of the above checks, we shouldn't use that token because we can't trust it. But once you've made it through all the above steps, your token should be valid and verified.

PS: Implementing these steps yourself is error-prone and a daunting task. Luckily there are various libraries in every programming language that handles most of this work for you.

Refresh Token

Because refresh token is an opaque token, it means that it can't be decoded and verified; thus, it can only be used in the token endpoint authorization server. Now the auth server grabs the refresh token, make sure it's still active, and then dispense a new access token and refresh token. Note that the revocation endpoint must be secured, for example, if someone gets a refresh token, they can each time(as long as refresh token not expired) generate new access and refresh token. We don't want this!

What Is OpenID Connect?

OpenID Connect (OIDC) is an authentication layer on top of OAuth 2.0. It provides the structure to a user profile, and allows you to selectively share it. So OIDC is just a special case of OAuth, and It's designed for Single Sign On(SSO) and sharing profile information. Like so GitHub, Twitter and many others use OIDC to share user profile information to clients.

On top of OAuth 2.0, OIDC adds another type of token: the ID Token. This token is highly defined and structured; it is mandated to be a JWT. Most of the times it contains the user profile information.

OIDC exposes user info endpoint to retreive user info. In general, this will retreive the exact user info which was available in the ID token itself. Thus, if you app trust the auth server that issued the token, we know who signed in and can use that to create a profile on our end. Note that OIDC supports only a subset of the OAuth grant types(we'll cover them in the next blog).

The great thing about OIDC is that the structure and names of token claims are entirely defined by the specification with isn't the case when using jusr the regular OAuth.

Wrap Up

In this blog, I've introduced you to the world of OAuth and OIDC. In the next part, we'll cover OAuth Grant Types.

If you have any feedback about my blogs. Please, don't hesitate to reach out to me or just say a "hello" on twitter: @HamzaLovesJava

Top comments (0)