A well-known technique for improving the run-time performance of a software system (in Python or any language) is function memoization. Memoization is a type of caching applied to a single function. If a function is called multiple times with the same arguments, repeating the calculation can be avoided by storing the results in a mapping (or on disk), keyed by the arguments. Upon subsequent calls, if the arguments are found, the stored result is returned.

This opportunity comes with tradeoffs. Memoization reduces time at the cost of space: previously calculated results must be stored either in memory or on disk. Additionally, the function memoized must be pure: the output must be determined exclusively by its inputs. Finally, not all types of function arguments are suitable. With in-memory memoization, where results are stored in a mapping, arguments must be hashable and immutable. With disk-based memoization, where results are stored in a file, arguments must be reducible to a unique file name; a message digest derived from a cryptographic hash function is optimal for this purpose.

Another challenge of memoization is cache invalidation: to avoid excessive cache growth, caches must be dropped. The Python standard library provides an in-memory solution with the functools.lru_cache() decorator. This decorator implements memoization with a "least recently used" (LRU) cache invalidation strategy: after reaching a maximum count, caches that have least-recently been used are dropped.

For Python programmers using Pandas DataFrames as function arguments, there are further challenges. As mutable containers, Pandas DataFrame and Series are not hashable. The functools.lru_cache() will fail if an argument is a Pandas DataFrame.

>>> import functools

>>> @functools.lru_cache

... def cube(v):

... return v ** 3

...

>>> import pandas as pd

>>> df = pd.DataFrame(np.arange(1_000_000).reshape(1000, 1000))

>>> cube(df)

Traceback (most recent call last):

TypeError: unhashable type: 'DataFrame'

StaticFrame is an alternative DataFrame library that offers efficient solutions to this problem, both for in-memory and disk-based memoization.

Hash Functions and Hash Collisions

Before demonstrating DataFrame memoization with StaticFrame, it is important to distinguish different types of hash functions.

A hashing function converts a variable-sized value into a smaller, (generally) fixed-sized value. A hash collision is when different inputs hash to the same result. For some applications, hash collisions are acceptable. Cryptographic hash functions aim to eliminate collisions.

In Python, the built-in hash() function converts hashable objects into an integer. Arbitrary types can provide support by implementing the magic method __hash__(). Importantly, the results of hash() are not collision resistant:

>>> hash('')

0

>>> hash(0)

0

>>> hash(False)

0

Python dictionaries use hash() to transform dictionary keys into storage positions in a low-level C array. Collisions are expected, and if found, are resolved with equality comparisons using __eq__(). Thus, for an arbitrary type to be hashable, it needs to implement both __hash__() and __eq__().

Cryptographic hashing functions are unlike hash(): they are designed to avoid collisions. Python implements a collection of cryptographic hashing functions in the hashlib library. These functions consume byte data and return, with the hexdigest() method, a message digest as a string.

>>> import hashlib

>>> hashlib.sha256(b'').hexdigest()

'e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855'

>>> hashlib.sha256(b'0').hexdigest()

'5feceb66ffc86f38d952786c6d696c79c2dbc239dd4e91b46729d73a27fb57e9'

>>> hashlib.sha256(b'False').hexdigest()

'60a33e6cf5151f2d52eddae9685cfa270426aa89d8dbc7dfb854606f1d1a40fe'

In-Memory Memoization

To memoize functions that take DataFrames as arguments, an immutable and hashable DataFrame is required. StaticFrame offers the FrameHE for this purpose, where "HE" stands for "hash, equals," the two required implementations for Python hashability. While the StaticFrame Frame is immutable, it is not hashable.

The FrameHE.__hash__() method returns the hash() of the labels of the index and columns. While this will collide with any other FrameHE with the same labels but different values, using just the labels defers the more expensive full-value comparison to __eq__().

The implementation of FrameHE.__eq__() simply delegates to Frame.equals(), a method that always returns a single Boolean. This contrasts with Frame.__eq__(), which returns an element-wise comparison in a Boolean Frame.

>>> f = sf.FrameHE(np.arange(1_000_000).reshape(1000, 1000))

>>> hash(f)

8397108298071051538

>>> f == f * 2

False

With a FrameHE as an argument, the cube() function, decorated with functools.lru_cache(), can be used. If lacking a FrameHE, the to_frame_he() method can be used to efficiently create a FrameHE from other StaticFrame containers. As underlying NumPy array data is immutable and sharable among containers, this is a light-weight, no-copy operation. If coming from a Pandas DataFrame, FrameHE.from_pandas() can be used.

In the example below, cube() is called with the FrameHE created above. The IPython %time utility shows that, after being called once, subsequent calls with the same argument are three orders of magnitude faster (from ms to µs).

>>> %time cube(f)

CPU times: user 8.24 ms, sys: 99 µs, total: 8.34 ms

>>> %time cube(f)

CPU times: user 5 µs, sys: 4 µs, total: 9 µs

While helpful for in-memory memoization, FrameHE instances can also be members of sets, offering a novel approach to collecting unique containers.

Creating a Message Digest from a DataFrame

While in-memory memoization offers optimal performance, caches consume system memory and do not persist beyond the life of the process. If function results are large, or caches should persist, disk-based memoization is an alternative.

In this scenario, mutability and hashability of arguments is irrelevant. Instead, cached results can be retrieved from a file with a name derived from the arguments. Applying a cryptographic hash function on the arguments is ideal for this purpose.

As such hash functions generally take byte data as input, a Frame and all of its components must be converted to a byte representation. A common approach is to serialize the Frame as JSON (or some other string representation), which can then be converted to bytes. As underlying NumPy array data is already stored in bytes, converting that data to strings is inefficient. Further, as JSON does not support the full range of NumPy types, the JSON input might also be insufficiently distinct, leading to collisions.

StaticFrame offers via_hashlib() to meet this need, providing an efficient way to provide byte input to cryptographic hash functions found in the Python hashlib module. An example using SHA-256 is given below.

>>> f.via_hashlib(include_name=False).sha256().hexdigest()

'b931bd5662bb75949404f3735acf652cf177c5236e9d20342851417325dd026c'

First, via_hashlib() is called with options to determine which container components should be included in the input bytes. As the default name attribute, None, is not byte encodable, it is excluded. Second, the hash function constructor sha256() is called, returning an instance loaded with the appropriate input bytes. Third, the hexdigest() method is called to return the message digest as a string. Alternative cryptographic hash function constructors, such as sha3_256, shake_256, and blake2b are available.

To create the input bytes, StaticFrame concatenates all underlying byte data (both values and labels), optionally including container metadata (such as name and __class__.__name__ attributes). This same byte representation is available with the via_hashlib().to_bytes() method. If necessary, this can be combined with other byte data to create a hash digest based on multiple components.

>>> len(f.via_hashlib(include_name=False).to_bytes())

8016017

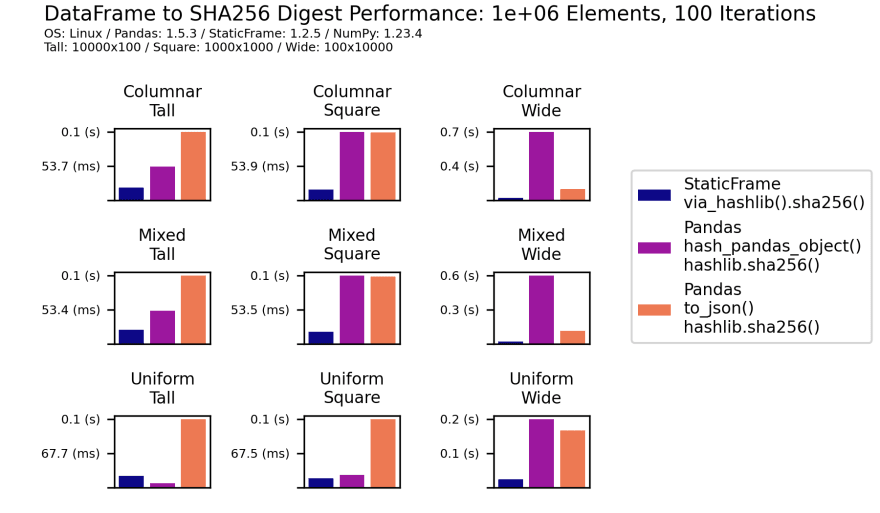

StaticFrame's built-in support for creating message digests is shown to be more efficient than two common approaches with Pandas. The first approach uses the Pandas utility function pd.hash_pandas_object() to derive per-column integer hashes. This routine uses a bespoke digest algorithm that makes no claim of cryptographic collision resistance. For comparison here, those per-column integer hashes are used as input to a hashlib message digest function. The second approach provides a JSON representation of the entire DataFrame as input to a hashlib message digest function. While this may be more collision resistant than pd.hash_pandas_object(), it is often slower. The following chart displays performance characteristics of these two approaches compared to via_hashlib(). Over a range of DataFrame shapes and type mixtures, via_hashlib() outperforms all except one.

Disk-Based Memoization

Given a means to convert a DataFrame into a hash digest, a disk-based caching routine can be implemented. The decorator below does this for the narrow case of a function that takes and returns a single Frame. In this routine, a file name is derived from a message digest of the argument, prefixed by the name of the function. If the file name does not exist, the decorated function is called and the result is written. If the file name does exist, it is loaded and returned. Here, the StaticFrame NPZ file format is used. As demonstrated in a recent PyCon talk, storing a Frame as an NPZ is often much faster than Parquet and related formats, and provides complete round-trip serialization.

>>> def disk_cache(func):

... def wrapped(arg):

... fn = '.'.join(func.__name__, arg.via_hashlib(include_name=False).sha256().hexdigest(), 'npz')

... fp = Path('/tmp') / fn

... if not fp.exists():

... func(arg).to_npz(fp)

... return sf.Frame.from_npz(fp)

... return wrapped

To demonstrate this decorator, it can be applied to a function that iterates over windows of ten rows, sums the columns, and then concatenates the results into a single Frame.

>>> @disk_cache

... def windowed_sum(v):

... return sf.Frame.from_concat(v.iter_window_items(size=10).apply_iter(lambda l, f: f.sum().rename(l)))

After first usage, performance is reduced to less than twenty percent of the original run time. While loading a disk-based cache is slower than retrieving an in-memory cache, the benefit of avoiding repeated calculations is gained without consuming memory and with the opportunity of persistent caches.

>>> %time windowed_sum(f)

CPU times: user 596 ms, sys: 15.6 ms, total: 612 ms

>>> %time windowed_sum(f)

CPU times: user 77.3 ms, sys: 24.4 ms, total: 102 ms

The via_hashlib() interfaces can be used in other situations as a digital signature or checksum of all characteristics of a DataFrame.

Conclusion

If pure functions are called multiple times with the same arguments, memoization can vastly improve performance. While functions that input and output DataFrames require special handling, StaticFrame offers convenient tools to implement both in-memory and disk-based memoization. While care must be taken to ensure that caches are properly invalidated and collisions are avoided, great performance benefits can be realized when repeated work is eliminated.

Top comments (0)