Before we get started the material/demos I used in this article are from - Tyler McGinnis' The Ultimate Guide to Hoisting, Scopes, and Closures in JavaScript. I tried to summarize the material as I understand it and tweaked the demos a bit to make the house metaphor work but his article is much more detailed and I highly encourage you check it out if you haven't already. Ok, let's jump in.

Before we get to hoisting, scope & closures, let's talk about Execution Context.

Execution Context context refers to how and which part of your code is currently active or accessible.

When you execute or run a JavaScript program the first Execution Context gets created and we can imagine as starting in an empty room-less house.

Initially our Execution Context is going to have two things. A global object (the empty room-less house) and a variable (something that can change) named this.

The name of our house is window when JavaScript runs in the browser.

Let's look at an example for what we see when we start JavaScript without any code:

As you can see, even without any code 2 things are created:

-

window- The empty house or global object. -

this- Our first variable which references (points to) our house.

This is our most simple Global Execution Context.

We haven't actually written any code yet. Let's fix that and begin to modify and do things in our house (Global Execution Context).

Execution Context Phases

Let's start by defining 3 variables that describe our house and running our code:

var roofColor = "pink";

var wallColor = "white";

function getHouseDescriptionRoom() {

return (

"Wow, what a nice " +

roofColor +

" roof on that " +

wallColor +

" house! 👀"

);

}

Every execution context is going to run in two steps. A Creation phase & an Execution phase:

Step 1 - Creation Phase

Step 2 - Execution Phase Phase

Another view:

In the Global Execution Context's Creation phase, JavaScript will:

- Create a global object, our house named

window. - Create an object called

thisthat references our house (window). - Set up memory space for variables and functions (I'll explain how these can be thought of as rooms in our house soon!).

- Assign variable declarations a default value of “undefined”.

- Place functions in memory (put the rooms in the house)

Now that JavaScript has prepared our house and the variables that we will need we can move onto the Execution phase which is where we step through our code one line at a time until we finish.

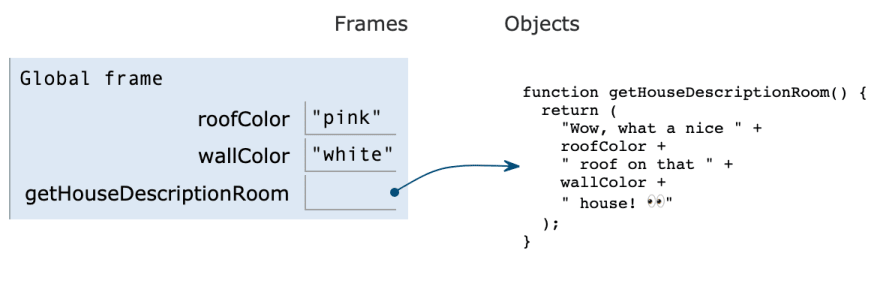

The gifs below shows this process:

To recap:

- We created a Global Execution Context with 2 variables (

roofColor&wallColor) and a function (getHouseDescriptionRoom). - During the

Creationphase of our Global Execution Context JavaScript the two variables we created are assigned an inital value ofundefinedand third variablegetHouseDescriptionRoomis created to store our function. - During the

Executionphase our code gets ran line by line and the variables get assigned their values.

Try the code out for yourself and give it a shot!

Let's look a little more closely at the Creation vs Execution phase. We are going to log(print) some values to the screen after the Creation phase but before they have gone through the Execution phase. Then we will log their values after the Execution phase.

// After Creation but before Execution

console.log("roofColor: ", roofColor);

console.log("wallColor: ", wallColor);

console.log("getHouseDescriptionRoom: ", getHouseDescriptionRoom);

// Execution step for our variables & Function

var roofColor = "pink";

var wallColor = "white";

function getHouseDescriptionRoom() {

return (

"Wow, what a nice " +

roofColor +

" roof on that " +

wallColor +

" house! 👀"

);

}

// After Creation and after Execution

console.log("roofColor: ", roofColor);

console.log("wallColor: ", wallColor);

console.log("getHouseDescriptionRoom: ", getHouseDescriptionRoom);

Before scrolling further spend some time looking at the code above and try to think about what is going to get logged to the console.

Here is the code you can play with for yourself:

Here is what get's logged:

// After Creation but before Execution

console.log("roofColor: ", roofColor); // roofColor: undefined

console.log("wallColor: ", wallColor); // wallColor: undefined

console.log("getHouseDescriptionRoom: ", getHouseDescriptionRoom); // getHouseDescriptionRoom: function getHouseDescriptionRoom() { return "Wow, what a nice " + roofColor + " roof on that " + wallColor + " house! 👀"; }

// Execution step for our variables & Function

var roofColor = "pink";

var wallColor = "white";

function getHouseDescriptionRoom() {

return (

"Wow, what a nice " +

roofColor +

" roof on that " +

wallColor +

" house! 👀"

);

}

// After Creation and after Execution

console.log("roofColor: ", roofColor); // roofColor: pink

console.log("wallColor: ", wallColor); // wallColor: white

console.log("getHouseDescriptionRoom: ", getHouseDescriptionRoom); // getHouseDescriptionRoom: function getHouseDescriptionRoom() { return "Wow, what a nice " + roofColor + " roof on that " + wallColor + " house! 👀"; }

As we can see after the Creation step our variables roofColor & wallColor are undefined as this is how they are initialized.

Once they are defined in the Execution step we then log their values which are now defined. This process of assigning values to variables during the Creation is referred to as Hoisting.

To be clear, when the program is runs/executes and we read or step over line 1, Creation Phase has already happened which is why the variables are undefined on the right in the Global Execution Context at this point. Execution Phase is when the program is running so the variables then get defined in the global frame after you step over lines 7 and 8. The variables here exist in the Global Execution Context which is why they are defined and available to use without having to call or invoke getHouseDescriptionRoom. You don't have to call a method for the variables in the Global Execution Context to be defined and available but they will only be so after the Creation Phase which happens in the background in preparation for the program to enter Execution Phase where line 1 begins.

Next, we'll explore Function Execution Context and begin to add rooms to our house (window).

Function Execution Context

Now we're going to use what we learned about the Global Execution Context to learn how Functions have their own Execution Context which we can think of as rooms in the house built for a specific purpose. A Function Execution Context is created whenever a function is invoked or called.

An Execution Context only gets created at the initialization of the JavaScript engine (Global Execution Context) and whenever a function is invoked (Function Execution Context).

So what's the difference between a Global Execution Context and a Function Execution Context? Let's take a look at the Creation phase:

- Create a

globalargument object, variables we can take into or that exist in the room. - Create an object called

this. - Set up memory space for variables and functions.

- Assign variable declarations a default value of “undefined”.

- Place functions in memory.

The only difference is that instead of a global object (window) getting created (we already have that) we create an arguments object which consists of variables we can take into or that exist in the room.

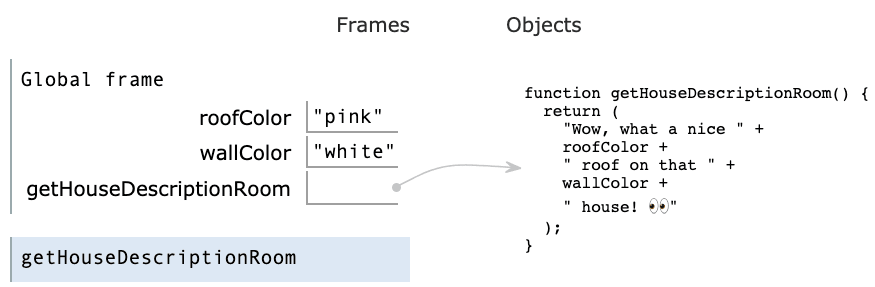

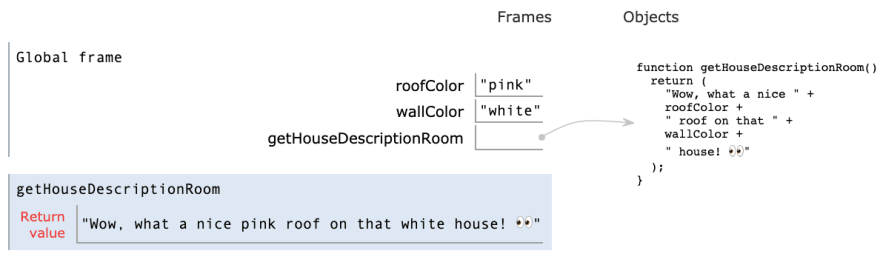

To see this in action let's take a look at what our code looks like when we invoke or step into our getHouseDescriptionRoom by adding this to our original code at the end: getHouseDescriptionRoom(). If you look back at the code you'll see that the only thing that happens when we visit this room in our house is that we return with a string that describes the house by using the variables in the Global Execution Context

Global Execution Context Creation Phase

Global Execution Phase Before getHouseDescriptionRoom is invoked

Function Execution Context Creation Phase

Function Execution Context Execution Phase

Step through the code yourself here:

Here is the code you can play with for yourself:

One thing to notice is that this function does not take any variables which is why the arguments object is empty. Another thing to notice is that once the getHouseDescriptionRoom is finished running it is removed from the visualizations. This represents the function being removed from the Execution/Call Stack. JavaScript uses this to order and execute functions one at a time. These are in the Frames column of the JavaScript Tutor visualizer. With “JavaScript Visualizer” the Execution Stack is shown in a nested fashion. You can think of this is as us leaving the room and stepping back into the house.

Remember that each function has it's own Execution context.

Let's take a look at another example:

function mainBedroom() {

console.log("In the mainBedroom");

function goToCloset() {

console.log("In goToCloset");

function findAShirt() {

console.log("In findAShirt");

}

findAShirt();

}

goToCloset();

}

mainBedroom();

Step through the Code:

If we look at the following gif, we can see that the mainBedroom function gets invoked which puts us in that room so to speak, it's Execution Context. In this function we then invoke goToCloset and step into a new room/Execution Context.

We then execute findAShirt which puts us in a new Execution Context and breaks our metaphor down a a bit but the concept remains. Each Execution Context has it's own variables & logic that gets performed inside of it. Once they are executed they are "popped off"/removed from the Execution / Call Stack.

Functions with Local Variables

We mentioned earlier that our function did not take any arguments or variables. Let's change that with a new example.

var firstName = "Elvis"

var lastName = "Ibarra";

function kitchen(name) {

var cupOfCoffee = "a hot cup of coffee"

return(name + " is in the kitchen holding " + cupOfCoffee);

}

console.log(kitchen(firstName));

Looking at the gifs below we can see that the variable cupOfCoffee exists inside of the kitchen's Execution Context. We are also doing something a little bit different and logging the return value of the kitchen function. One way to think of this is that we are leaving the function's Execution Context with a return value and executing that value in the Global Execution Context.

Now we can introduuce a new term Scope which similar to Execution Context refers to where our variables are accessible.

Local Scope refers to everything inside of a function (the rooms in the house) and Global Scope are variables/methods accessible in our Global Execution Context (in the house but not in the rooms).

Step through the Code:

Any arguments that you pass into a function will be local variables in that function's Execution Context. In this example, firstName & lastName exist as a variables in the Global Execution context (where they are defined) and in the kitchen Execution Context where it was passed in as an argument.

Finally, our variable cupOfCoffee is a local variable in the kitchen Execution Context.

Let's take a look at another example. What get's logged in the example below?

function backyard() {

var lawnChair = "is in the backyard"

}

backyard()

console.log(lawnChair);

Let's step through the code line by line. First, after the Global Execution Creation Step we have created a variable which stores our function backyard in memory and nothing else has happened. From here we move onto line 5 which is the next line that we will execute. Our current state looks like this:

After we execute line 5 our backyard Execution Context (local scope) undergoes a Creation phase in which the variable lawnChair is initialized with a value of undefined. We will define it on line 2 in the next step.

Line 2 executes which defines our variable lawnChair with the string value is in the backyard. Since we did not specify a return for this function, by default it is undefined.

Next this function will complete it's Execution Context and be popped off the Execution / Call Stack and it's variables/methods will no longer be available to the Global Execution Context (Global Frame in these images). Note the function get's removed from the Frames column. At this point we have left the backyard and stepped back into the house.

Now that line 5 has finished executing we can execute the final line 7:

An error! What's going on? In the Global Execution context we are logging the variable lawnchair which is defined and exists in the backyard's Execution Context. Another way of saying this is that the lawnchair is a local variable defined in the function backyard which is inaccessible in the Global Scope. Or, since we stepped back into the house, we can't use the lawn chair since it's outside in the backyard.

What if there's more than one local scope? Well, let's get a little tricky and put some gnomes on our lawn, what get's logged here and in what order? (Try and answer for yourself before scrolling further...)

function gnome1 () {

var name = 'Begnym'

console.log(name)

}

function gnome2 () {

var name = 'Jinzic'

console.log(name)

}

console.log(name)

var name = 'Borwass'

gnome1()

gnome2()

console.log(name)

The result is undefined, Begnym, Jinzic, & Borwass in that order. This is because each gnome has it's own local scope and although the variable name exists in both the local and the global scope JavaScript first looks inside the scope of the function that is currently executing.

Step through the Code:

You should be asking... well what if a variable exists in the Global scope but not in the Local scope? Well, check this out:

var gnome1 = 'Begnym';

function logName () {

console.log(gnome1);

}

logName();

Step through the Code:

As we can see if the variable does not exist in the Local scope JavaScript will look to the Global Scope (Execution Context) and if it exists there will use that value. This is why the logged value is Begnym. This process of looking in the Local scope first for a variable and then in the global scope is known as the Scope Chain.

For the last example I want to show what happens when a variable exists in a parent Execution Context (Scope) which as been popped off the Execution / Call Stack. For this example, let's do some laundry:

Try to read the code below and guess what the final logged value will be:

var shirts = 0

function fillLaundryBasket(x) {

return function addMore (y) {

return x + y;

};

}

var grab5 = fillLaundryBasket(5);

shirts += grab5(2)

console.log(shirts)

Let's step through the code again but this time I'll jump to the good parts. First we'll invoke the function fillLaundryBasket on line 5 with the argument 5 and save the return value in a variable called grab5. This creates the Local fillLaundryBasket Execution Context with an x variable with a value of 5.

This results in the grab5 variable pointing to the returned AddMore function with the defined x variable. The fillLaundryBasket Execution Context gets removed from the Execution / Call Stack but although it's variables are removed, as we'll see in the next step, nested functions have access to the parent's variables.

Next we'll step through line 10 which adds the return value of grab5 with an argument of 2. As we can see from the screenshot the addMore Execution Context still has the x value of 5 although fillLaundryBasket is no longer the Local scope. This is why the return and logged value is 7.

The scope in which the x value exists has a special name known as the Closure scope and is best visualized in the JavaScript Visualizer. The concept of a child "closing" the variables including the parent is called Closures.

Hopefully the house metaphor helps you understand Execution Context a little bit better. The best way to learn is to walk through the code yourself and start experimenting. You can make your house/rooms as simple or complex as you want and as you get comfortable you'll find yourself building/creating your dream house (program). Have fun!

That's it! Thanks again to Tyler McGinnis for the inspiration and the original material 🙏 🙂 .

Top comments (0)