How a simple manual change in an AWS Security Group using the AWS Web Console can have bitter security consequences

In this article, we’ll show how a simple manual change in an AWS Security Group using the AWS Web Console can have bitter security consequences. This one is based on many first-hand experiences and user feedback, in a production context with infrastructure-as-code.

Allowing PgSQL (with Terraform)

For this article, we’ll take the example recently experienced by a team we know. They secured access to their PgSQL instances with this simple Terraform configuration, allowing only the web servers subnet:

// Secure the PgSQL RDS cluster using a dedicated SG

resource "aws_security_group" "pgsql" {

name = "PgSQL Security Group"

description = "PgSQL Security Group"

tags = {

Name = "PgSQL Security Group"

}

}

// PgSQL can only be accessed from the WWW network (10.0.0.0/8)

resource "aws_security_group_rule" "pgsql" {

type = "ingress"

from_port = 5432

to_port = 5432

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/8"]

security_group_id = aws_security_group.pgsql.id

}

They had a scheduled terraform plan as a GitHub Action for the whole infrastructure, so if something changed, it was reported right away. The “GitOps” workflow also included some linters, a terraform plan, followed by a terraform apply after a merge on the main branch.

It worked well and satisfied the initial basic security requirements. Good job!

That one Security Group temporary change

A couple of years later, to win a new major customer, they agreed to allow a pentesting audit. Long story short, one auditor was pentesting from the internet, while the other worked from different internal networks of the company.

Oddly enough, they didn’t come back with the same results: the external audit came clean, while the internal one basically opposed a strict “no-go” to the commercial deal. Reason: the auditor reported he gained access to every customer database in a matter of minutes. With proof.

How could it happen?

One day, someone from the team needed to quickly test something on a customer database who experienced a bug. A single value to change. Going through the hassle of switching to the secure network, then connecting to the corporate VPN, then going through the Bastion using a smartcard for authentication, probably also having to explain soon to the security team why he connected and what he did…this was definitely too much. Especially when he could simply allow the company’s office outgoing IPv4 on the “PgSQL” security group! And remove it after the change. Moreover, he would necessarily remember about it, as all the Security Groups were 100% managed by Terraform on CI.

And it worked well! That team member fixed the customer issue in the database quickly.

And forgot to remove the security group rule, until it was discovered by the auditor, so that he could:

connect painlessly to the customer databases from the office

then easily find passwords using a tool like hydra against PostgreSQL.

profit.

How we ended up there?

Here’s the context in which this team worked:

a team member had AWS Web Console credentials large enough to make Security Group changes

they assumed Security Group Rules were represented similarly on AWS and Terraform

they wrote their Security Groups rules a certain way using Terraform

We can’t do much about the first issue: it’s the harsh reality of most companies today. Surely enough they need to adopt a proper full GitOps workflow, but most aren’t there yet (and won’t be for a while).

The lists are not what they seem

The second assumption is confusing because of what can the UI lead you to believe. As developers, we know that cidr_blocks = ["10.0.0.0/8"] is a list and that adding an element to it will make it different.

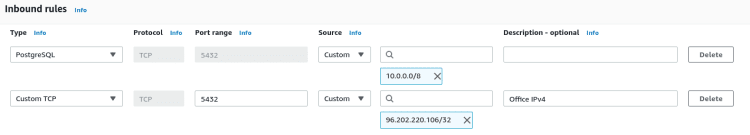

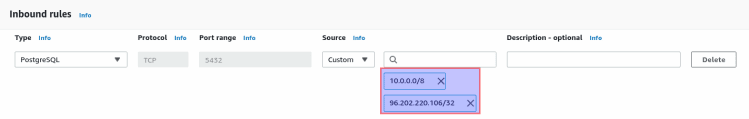

As a developer, I can also easily believe that such a design in the AWS Console would also generate a list, both IPs are listed under the same line, exactly as if I read ["10.0.0.0/8", "96.202.220.106/32"]:

The thing is, in the end, on the AWS side, they really are two elements of a list, but in the Terraform model, they end up being two distinct resources and not two elements. This difference in models between the cloud provider and Terraform can sometimes be misleading for users and can have major consequences.

The way you write your Terraform matters

The third and final situation here is the way the Terraform configuration was written.

Can you guess what happened in CI for months after the manual change wasn’t reverted? Nothing.

$ terraform apply

aws_security_group.pgsql: Refreshing state... [id=sg-0b6af725ba7e7691b]

aws_security_group_rule.pgsql: Refreshing state... [id=sgrule-3696232291]

Apply complete! Resources: 0 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

To be more precise, something happened. The manual Security Group rule change was added without anyone being notified about it in the terraform.tfstate right when the next terraform apply ran in CI:

"ingress": [

{

"cidr_blocks": [

"10.0.0.0/8"

],

"description": "",

"from_port": 5432,

"ipv6_cidr_blocks": [],

"prefix_list_ids": [],

"protocol": "tcp",

"security_groups": [],

"self": false,

"to_port": 5432

},

{

"cidr_blocks": [

"96.202.220.106/32"

],

"description": "",

"from_port": 5432,

"ipv6_cidr_blocks": [],

"prefix_list_ids": [],

"protocol": "tcp",

"security_groups": [],

"self": false,

"to_port": 5432

}

],

Yes, you will end up with a Terraform state with way more information and resources than you intended from the code, as the Terraform state job is not to represent your intention, but to map the real world with your config.

The way Security Group Rules were written couldn’t help discovering the change (not to mention notifying anyone). You could add a billion rules and it would be the same.

Fortunately, in this case, if you read Terraform’s documentation for the AWS provider (currently v3.36), you’ll find 2 options to configure Security Groups:

Use the aws_security_group resource with inline egress {} and ingress {} blocks for the rules.

Use the aws_security_group resource with additional aws_security_group_rule resources.

In this case, using the first option would have been better for this team, from a more DevSecOps point of view. See how the next terraform apply in CI would have had the expected effect:

$ terraform apply

aws_security_group.pgsql: Refreshing state... [id=sg-03a12201c68c38d92]

An execution plan has been generated and is shown below.

Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

~ update in-place

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# aws_security_group.pgsql will be updated in-place

~ resource "aws_security_group" "pgsql" {

id = "sg-03a12201c68c38d92"

~ ingress = [

- {

- cidr_blocks = [

- "96.202.220.106/32",

]

- description = "Allow PgSQL from WWW"

- from_port = 5432

- ipv6_cidr_blocks = []

- prefix_list_ids = []

- protocol = "tcp"

- security_groups = []

- self = false

- to_port = 5432

},

# (1 unchanged element hidden)

]

name = "PgSQL Security Group"

tags = {

"Name" = "PgSQL Security Group"

}

# (6 unchanged attributes hidden)

}

Plan: 0 to add, 1 to change, 0 to destroy.

Unfortunately, it’s often too late when you realize it, and this kind of option doesn’t exist for every resource out there. What was a DevOps discussion (“let’s automate those deployments and ship that on CI!”) can quickly become a DevSecOps discussion now (“how should we write our Terraform configuration according to our goals?”).

The driftctl option

That’s why using driftctl is always a good option. As the tool compares your Terraform state to the reality of your AWS account, you can deploy the tool at 2 important places of your workflow:

as a scheduled run (like an hourly cronjob), so you get reports when something changes

as a pre-condition to a terraform apply step in CI: so you ensure you’re working with an unmodified Terraform state (as by design the refresh part of the apply can modify it). You may also want to parallelize this driftctl step with a terraform plan.

Here’s a driftctl run when the activity is as expected on the AWS account:

$ driftctl scan

Scanned resources: (54)

Found 2 resource(s)

- 100% coverage

Congrats! Your infrastructure is fully in sync.

$ echo $?

0

Here’s a driftctl run with the above manual change:

$ driftctl scan

Scanned resources: (55)

Found resources not covered by IaC:

aws_security_group_rule:

- Type: ingress, SecurityGroup: sg-0ce251e7ce328547d, Protocol: tcp, Ports: 5432, Source: 96.202.220.106/32

Found 3 resource(s)

- 66% coverage

- 2 covered by IaC

- 1 not covered by IaC

- 0 missing on cloud provider

- 0/2 changed outside of IaC

$ echo $?

1

This output clearly shows:

a resource NOT on the Terraform state, of type aws_security_group_rule, for the Security Group sg-0ce251e7ce328547d, that allows TCP/5432 for 96.202.220.106/32. This should trigger an alarm!

some metrics for your own reference.

This output can be exported as JSON too, so you can easily manipulate it and integrated it into your other tools and notification systems. There’s a ton of other options and integrations you can use with driftctl, but that will be for another article!

Reference:

Terraform AWS Provider resources documentation: aws_security_group_rule and aws_security_group

Top comments (0)