Disk reads are 4x (for SSD) to 80x (for magnetic disk) slower as compared to main memory (RAM) reads and hence it becomes extremely important for a database to utilize main memory as much as it can, and be super-performant while keeping its latencies to a bare minimum. Engines cannot simply replace disks with RAM because of volatility and cost, hence it needs to strike a balance between the two - maximize main-memory utilization and minimize the disk access.

The database engine virtually splits the data files into pages. A page is a unit which represents how much data the engine transfers at any one time between the disk (the data files) and the main memory. It is usually a few kilobytes 4KB, 8KB, 16KB, 32KB, etc. and is configurable via engine parameters. Because of its bulky size, a page can hold one or multiple rows of a table depending on how much data is in each row i.e. the length of the row.

Locality of reference

Database systems exhibit a strong and predictable behaviour called locality of reference which suggests the access pattern of a page and its neighbours.

Spatial Locality of Reference

The spatial locality of reference suggests if a row is accessed, there is a high probability that the neighbouring rows will be accessed in the near future.

Having a larger page size addresses this situation to some extent. As one page could fit multiple rows, this means when that page is cached in main memory, the engine saves a disk read if the neighbouring rows residing on the same page are accessed.

Another way to address this situation is to read-ahead pages that are very likely to be accessed in the future and keep them available in the main memory. This way if the read-ahead pages are referenced, the engine needs to go to the disk to fetch the page, rather it will find the page residing in the main memory and thus saving a bunch of disk reads.

Temporal Locality of Reference

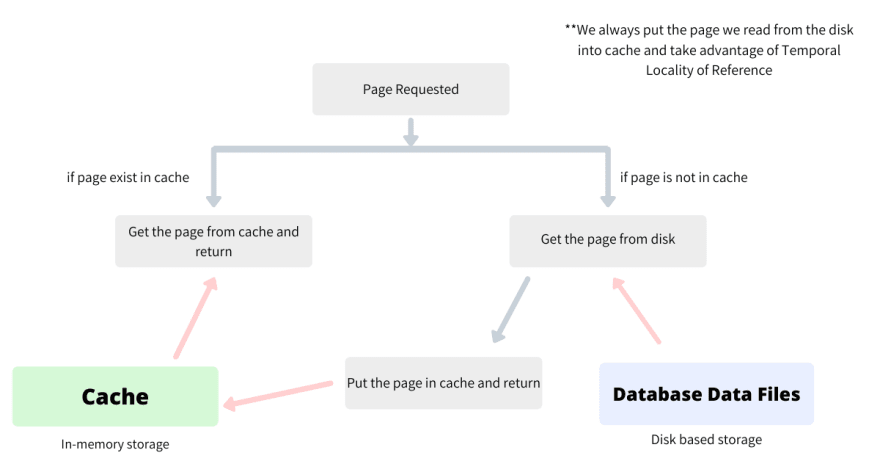

The temporal locality of reference suggests that if a page is recently accessed, it is very likely that the same page will be accessed again in the near future.

Caching exploits this behaviour by putting every single page accessed from the disk into main-memory (cache). Hence the next time a page which is available in the cache is referenced, the engine need not make a disk read to get the page, rather it could reference it from the cache directly, again saving a disk read.

Since the cache is very costly, it is in magnitude smaller in capacity than the disk. It can only hold some fixed number of pages which means the cache suffers from the problem of getting full very quickly. Once the cache gets full, the engine needs to evict an old page so that the new page, which according to the temporal locality of reference is going to be accessed in the near future, could get a place in the cache.

The most common strategy that decides the page that will be evicted from the cache is the Least Recently Used cache eviction strategy. This strategy uses Temporal Locality of Reference to the core and hence evicts the page which was not accessed the longest, thus maximizing the time the most-recently accessed pages are held in the cache.

LRU Cache

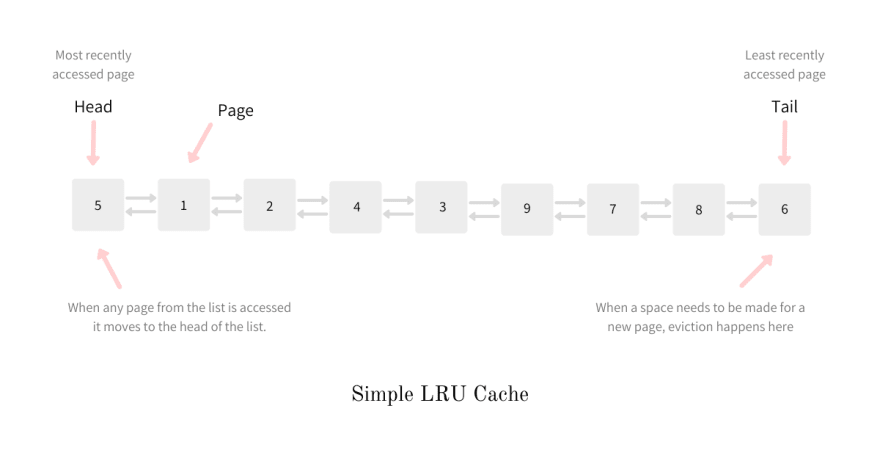

The LRU cache holds the items in the order of its last access, allowing us to identify which item is not being used the longest. When the cache is full and a newer item needs to make an entry in the cache, the item which is not accessed the longest is evicted and hence the name Least Recently Used.

The one end (head) of the list holds the most-recently referenced page while the fag end (tail) of the list holds the least-recently referenced one. A new page, being most-recently accessed, is always added at the head of the list while the eviction happens at the tail. If a page from the cache is referenced again, it is moved to the head of the list as it is now the most-recently referenced.

Implementation

LRU cache is often implemented by pairing a doubly-linked list with a hash map. The cache is thus just a linked list of pages and the hashmap maps the page_id to the node in the linked list, enabling O(1) lookups.

InnoDB's Buffer Pool

MySQL InnoDB's cache is called Buffer Pool which does exactly what has been established earlier. Pseudocode implementation of get_page function, using which the engine gets the page for further processing, could be summarized as

def get_page(page_id:int) -> Page:

# Check if the page is available in the cache

page = cache.get_page(page_id)

# if the page is retrieved from the main memory

# return the page.

if page:

return page

# retrieve the page from the disk

page = disk.get_page(page_id)

# put the page in the cache,

# if the cache is full, evict a page which is

# least recently used.

if cache.is_full():

cache.evict_page()

# put the page in the cache

cache.put_page(page)

# return the pages

return page

A notorious problem with Sequential Scans

Above caching strategy works wonders and helps the engine to be super-performant. Cache hit ratio is usually more than 80% for mid-sized production-level traffic, which means 80% of the times the pages were served from the main memory (cache) and the engine did not require to make the disk read.

What would happen if an entire table is scanned? say, while talking a DB dump, or running a SELECT without WHERE to perform some statistical computations.

Going by the MySQL's aforementioned behaviour, the engine iterates on all the pages and since each page which is accessed now is the most recent one, it puts it at the head of the cache while evicting one from the tail.

If the table is bigger than the cache, this process will wipe out the entire cache and fill it with the pages from just one table. If these pages are not referenced again, this is a total loss and performance of the database takes a hit. The performance will pickup once these pages are evicted from the cache and other pages make an entry.

Midpoint Insertion Strategy

MySQL InnoDB Engine ploys an extremely smart solution to solve the notorious problem with Sequential Scans. Instead of keeping its Buffer Pool a strict LRU, it tweaks it a little bit.

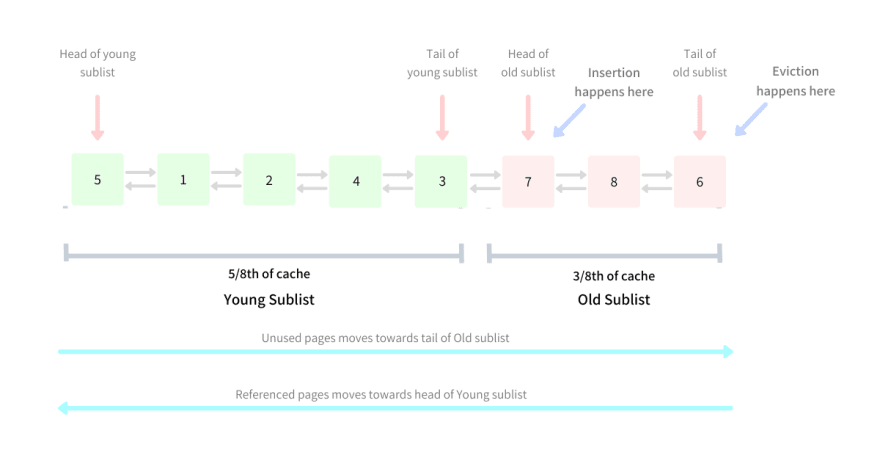

Instead of treating the Buffer Pool as a single doubly-linked list, it treats it as a combination of two smaller sublists - usually 5/8th and 3/8th of the total size. One sublist holds the younger data while the other one holds the older data. The head of the Young sublist holds the most recent pages and the recency decreases as we reach the tail of the Old sublist.

Eviction

The tail of the Old Sublist holds the Least Recently Used page and the eviction thus happens as per the LRU Strategy i.e. at the tail of the Old Sublist.

Insertion

This is where this strategy differs from Strict LRU. The insertion, instead of happening at "newest" end of the list i.e. head of Young sublist, happens at the head of Old sublist i.e. in the "middle" of the list. This position of the list where the tail of the Young sublist meets the head of the Old sublist is referred to as the "midpoint", and hence the name of the strategy is Midpoint Insertion Strategy.

By inserting in the middle, the pages that are only read once, such as during a full table scan, can be aged out of the Buffer Pool sooner than with a strict LRU algorithm.

Moving page from Old to the Young sublist

In this strategy, like in Strict LRU implementation, whenever the page is accessed it moves to the newest end of the list i.e. the head of the Young sublist. During the first access, the pages make an entry in the cache in the "middle" position.

If the page is referenced the second time it is moved to the head of Young sublist and hence stays in the cache for a longer time. If the page, after being inserted in the middle, is never referenced again (during full scans), it is evicted sooner because the Old sublist is usually shorter than the Young sublist.

The Young sublist thus remains unaffected by table scans bringing in new blocks that might or might not be accessed afterwards. The engine thus remains performant as more frequently accessed pages continue to remain in the cache (Young sublist).

MySQL parameter to tune the midpoint

InnoDB allows us to tune the midpoint of the buffer pool through the parameter innodb_old_blocks_pct. This parameter controls the percentage of Old sublist to Buffer Pool. The default value is 37 which corresponds to the ratio 3/8.

In order to get greater insights about Buffer Pool we can invoke the following command as

$ SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUS

----------------------

BUFFER POOL AND MEMORY

----------------------

Total memory allocated 137363456; in additional pool allocated 0

Dictionary memory allocated 159646

Buffer pool size 8191

Free buffers 7741

Database pages 449

Old database pages 0

...

Pages made young 12, not young 0

43.00 youngs/s, 27.00 non-youngs/s

...

Buffer pool hit rate 997 / 1000, young-making rate 0 / 1000 not 0 / 1000

Pages read ahead 0.00/s, evicted without access 0.00/s, Random read ahead 0.00/s

...

The command SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUS outputs a lot of interesting metrics but the most interesting and critical ones, w.r.t Memory and Buffer Pool, are

- number of pages that were made young

- rate of eviction without access

- cache hit ratio

- read ahead rate

Conclusion

We see how by changing just one aspect of LRU cache, MySQL InnoDB makes itself Scan Resistant. Sequential scanning was a critical issue for the cache but it was addressed in a very elegant way.

References

- Latency numbers

- Locality of reference

- InnoDB: Making Buffer Cache Scan Resistant

- MySQL Dev - Buffer Pool

- MySQL Dev - Making the Buffer Pool Scan Resistant

- MySQL Dev - InnoDB Disk I/O

Other articles you might like:

- Building Finite State Machines with Python Coroutines

- Solving an age-old problem using Bayesian Average

- Eight rituals to be a better programmer

- Pseudorandom numbers using Cellular Automata - Rule 30

- Overload Functions in Python

This article was originally published on my blog - What makes MySQL LRU cache scan resistant.

If you liked what you read, subscribe to my newsletter and get the post delivered directly to your inbox and give me a shout-out @arpit_bhayani.

Top comments (0)