Since my team is currently hiring, how we go about hiring for tech roles is very much on my mind right now. I’ve participated in hiring on three different teams now (on both sides of the hiring equation), and my own thinking and process has evolved.

Designing an interview gauntlet

On my first team, I transitioned from being a freelance contractor to a full-time hire and never experienced their interview process. So, when I was asked to hire additional front-end talent, I was a bit overwhelmed with the task. I had heard of the whiteboard interviews that are common in tech (and were used by the back-end team), but that activity seemed so far removed from the daily job as to be meaningless. While I’m proud of that choice, I also admit that my sense of what was useful to ask in an interview was still pretty underdeveloped. Desparate for guidance, much of the process I used was informed by a CSS-Tricks article on front-end interviews.

Looking back over these interview questions, I see now that they focus mainly on testing a candidate’s knowledge and tactics:

- Name 3 ways to decrease page load (perceived or actual load time).

- Let’s say you start a new project right now –- what solution would you choose for adding custom icons to the project?

- What CSS units do you commonly use?

- List as many values for the display property that you can remember. (This one really makes me wince now.)

After enduring a gauntlet of quiz questions, candidates were invited to an in-person interview which included more quiz-style questions and a coding activity, also cribbed from the CSS-Tricks article. We provided candidates the image below and a set amount of time to recreate the button in CodePen (with explicit free reign to search the web for anything they normally would look up):

While I wouldn’t be keen to use this activity now, it was relevant to the job at hand, where both being able to spot important details in comps and recreate them with pixel-perfect precision was a requirement. It definitely tested candidates and even enraged one who, after twenty minutes, glared directly at me and then my boss and said, “It’s not like she could do this either.”

The candidate was wrong (I had timed myself recreating the button), but I didn’t feel good about pushing someone to that point of frustration and definitely felt the interview process could be improved. We eventually replaced this specific activity with recreating a nav element that existed in one of our products – it had similar complexity to the button, but it was spread out over more elements and somehow didn’t feel as grueling.

Lessons learned

- Anything I ask a candidate to do during the interview should have immediate relevance to what the job asks of them. Essentially, no whiteboarding; if you ask a candidate to write code, they should be able to do so in a familiar code editor with the tooling they’re accustomed to.

- Avoid questions that can and should be resolved with a web search or a visit to MDN. Knowing stuff is definitely important to the job, but outright quizzing candidates isn’t as revealing as one might hope and adds extra stress into an already fraught process.

- Tricky “gotcha questions” don’t feel good as a candidate or as an interviewer.

A better understanding of the interview process

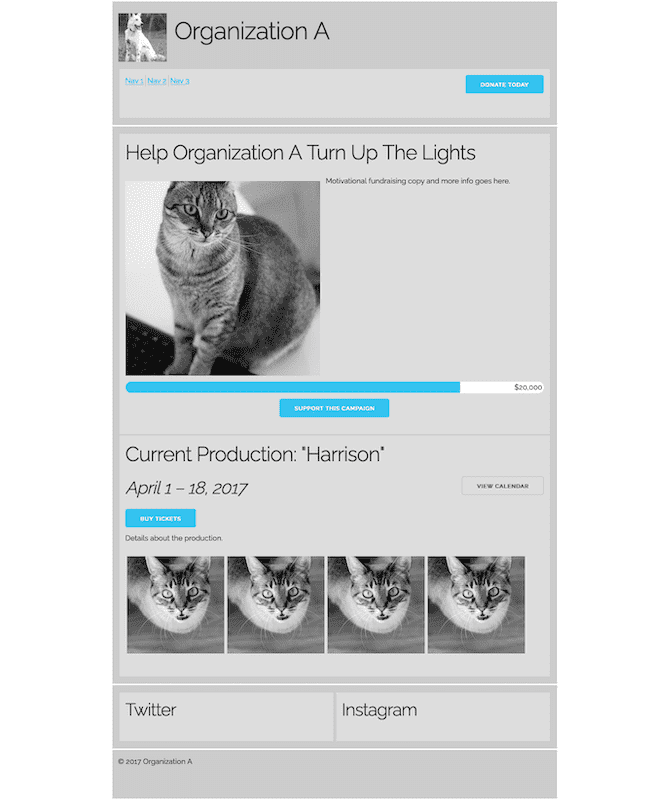

Interviewing for my next role, I had my first experience of being on the other side of an interview activity. After two screening interviews, I did a series of remote interviews and was given a timed activity. I was given a problem spec sheet that outlined a variety of information that might be included on an organization’s profile and asked to design wireframes for two different organizations, showing how I would handle the competing needs of the information.

While it was not explicit that this would be a coding exercise, I work faster in HTML and familiar CSS frameworks than I do in programs like Figma or Sketch, so I created two HTML documents using a combination of the Skeleton CSS framework, jQuery and PlaceIMG:

I wrote just under 100 lines of HTML, 125 lines of Sass and 40 lines of JS in the allotted time, which seems like a miniscule effort in comparison to some of the take-home activities assigned to candidates these days. However, the hiring committee wasn’t expecting any code at all, so presenting a wireframe that had animations and hover effects definitely made me stand out.

More importantly, while some of the interview questions I was asked did touch on my opinions about tech topics, the vast majority of the questions were about how I approached problem solving overall and how I collaborated with others. The interview, as a result, felt more like a conversation than a quiz.

After being hired, I participated in the hiring process for coworkers both on and off the dev team and gained new appreciation for how this thoughtful process came to be. As a member of hiring committees, I was asked to take implicit association tests to understand my unconcious biases and also given rubrics by which to grade candidates, helping us keep the important criteria for the role front of mind and providing some quantitative data to a process that can be ruled—disasterously so—by instinct.

Lessons learned

- Good hiring processes come out of very thoughtful consideration about the outcomes you want and the things that might get in the way of those outcomes. For example:

- For many folks participating in the hiring process, it’s on top of their normal job, so providing guidance is necessary to steer things in the right direction.

- Bias has the potential to affect every stage of a hiring process. Deal with that head on vs pretending otherwise.

- Hiring conversations should feel exactly like that—conversations—and not oral exams.

- Bonus lesson: Avoid asking candidates to solve design problems your team is currently working on. While the activity presented to me in my interview for this job wasn’t a source of frustration at the time, I soon learned that it was something that was in the upcoming work queue for the team. In retrospect, I would avoid interview problems like this because it’s entirely possible to create a conflict where you don’t hire the candidate with the best solution (for a variety of valid reasons). If you go forward using anything suggested or created by an un-hired candidate during the interview process, you’ve essentially gotten free work out of them. Better to avoid this possibility alltogether.

My best, current thinking on hiring

For my current role, I had an informal conversation with the hiring manager followed by an all-day on-site interview with members of the dev team and the organization overall, including the CEO. The phone screen felt like a conversation, while the team interview clearly worked from a script of questions. Additionally, a couple of days before the on-site, I was presented with a JavaScript code sample and a matching test, and asked to review the code and be prepared to discuss it. The email introducing this code included this note, which I found to be a great display of kindness:

Please don’t overanalyze the code too much - we’re not here to ask trick questions, but to instead engage with you as you read this code and share thoughts about it.

It’s rare for anything in an interview process to put candidates at ease— but this did it for me. I probably read this sentence ten times before my interview. I remember it now, over a year later. Not only did it make me feel comfortable with the code review, it made me excited to meet the people at the other end of the email who were invested in treating candidates so kindly.

I’m currently doing my first round of hiring for Lumen’s front-end team and am grateful for my years of experience—hiring and as a candidate—that have informed this process. I’m building onto a process that has been updated since I was hired and hope my changes improve the process for candidates and, assuming we make a successful hire, are adopted by the rest of the team.

Things I’ve added to our process:

- Inspired by our VP of Product who included specific references to Lumen’s company values of commitment, openness, generosity and creativity in a recent job description, I’ve done the same for our engineering team (see the job description). Being successful at Lumen means being invested in those values and our educational mission.

- Created documentation about the process for the hiring committee and others involved in the hiring process. This provides a consolidated, shared resource for everyone and also allows me to remind folks of the importance of hiring. It’s easy for it to feel like an add-on, an extra ask on your work day, but I truly believe it’s some of the most important work we’ll do this month.

- Requirement for all involved in the hiring process to complete a handful of implicit association tests and read two articles, one about the downsides of hiring for “culture fit” and examples of unconcious bias in hiring.

- Added a request for a candidate’s pronouns before the first interview. This prevents interviewers from doing any guesswork and hopefully signals to candidates that we care about having a respectful working relationship.

- Instead of scouring online lists of “front-end interview questions,” as I did in my first hiring role, I’ve taken inspiration from how our learning team thinks about assessments. Before writing exam questions, first there’s an understanding of the learning outcomes of the chapter. So, I got clear about what I want to learn about a candidate at each stage of our interview process and created a document with those headings. Only after I knew what knowledge I was after did I look at our existing interview questions, selecting those that help us learn those things or drafting new questions/discusion points when none of the existing questions proved useful to my goals.

- We’ve adapted the original code conversation to instead be a take-home code review exercise and, for this search, I updated that to have a front-end component. Additionally, I added some more specific prompts and questions as part of the code review to better understand a candidate’s previous experience with code review.

- Provide a rubric/scale for evaluation from the hiring committee, in addition to our more standard conversational evaluation. My goal here is to prevent the hiring committee from being too swayed by who speaks first or a good candidate from being skipped over because of bias.

Lessons learned

This process is ongoing—as in, we’re currently conducting interviews—so it’s too early to sum things up in a tidy bow. However, two things stand out to me at this point:

- Like so many other things, the hiring process is iterative. I’m learning things all the time, which allows me to refine and improve whatever my current best guess about how to do this. You also get to a better result faster if you get insight from more folks. Listen to your team if they say they would be put off by a question or request or express that they wouldn’t be succeed at your activity; none of these are good signs.

- Know your WHY. Why are we asking this question? What do we want to learn? Also: Why are we asking for pronouns? Why do we need to do this bias exercise? I haven’t been asked these questions in our current process, but I’m prepared for them—most specifically because I didn’t ask for permission for these changes to our process, I just implemented them.

And that really touches on part of why I think hiring is so important. It’s not just adding new team members, it’s also a moment for the current team to reflect on about what they value, what the team culture is—to celebrate that and to make adjustments. Especially on the smaller teams I love to lead and work on, hiring has a huge impact on all of us, which is why I spend so much time thinking about it…and, now, writing about it.

Top comments (0)