Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm

☕️ Read this article on my blog

Equality of values in JavaScript: for years, this has been a quite obscure topic for me. How many times have I been confused by an if statement behaving in a surprising way, I cannot count. So: what are we talking about anyway? Check out this piece of code:

const userA = {firstname: 'John', lastname: 'Doe'}

const userB = {firstname: 'John', lastname: 'Doe'}

if (userA === userB) {

console.log('Both users are the same')

} else {

console.log('Users A and B are different')

}

What do you think the output will be when this code runs? Think about it for a second.

✅ If your answer was 💡 Reveal answer

Users A and B are different, you're right, congrats 🍾

Does this answer surprise you? Well, that is what we are going to talk about in this blog post. So let's clarify this, shall we?

1. Value types

The first step in understanding the equality of values is knowing the possible types for these values. In our JavaScript universe, we manipulate values all the time, and they can either be primitive values, or they can be of a special type.

1.1. Primitive values

Here is the exhaustive list of all the primitive values that we can encounter in our universe, with examples:

- booleans =>

true/false - numbers =>

7,42,2048, ... - bigints =>

6549846584548n(the n at the end is what makes it a BigInt - strings =>

"Apple" - symbols =>

Symbol() - undefined =>

undefined - null =>

null

That's it. Please note that there is only one possible value for the primitive type undefined, and that is... undefined. The same goes for the type null:

console.log(typeof(undefined)) // undefined

console.log(typeof(null)) // null

I am now gonna make a statement that might shock you, brace yourself, you'll be alright:

All primitive values already exist in the JavaScript universe

This means it's impossible to create a brand new value of a primitive type. I know, weird, right? When you do this:

let likes = 0

let views = 0

You are creating two variables that point to the already existing value 0, which is a number. This can be represented as the following:

It's even more surprising when we talk about strings:

let name = "John Doe"

The string "John Doe" isn't actually created out of nowhere, it already exists, you're just pointing to it. This might sound crazy, but it's crucial to understand when it comes to equality of values. Just imagine a world where all possible values for each primitive type already exist, waiting for a variable to point to them.

Knowing this, it becomes obvious that those assertions are all truthy:

console.log('John Doe' === 'John Doe') // ✅ true

console.log(42 === 42) // ✅ true

console.log(null === null) // ✅ true

console.log(undefined === undefined) // ✅ true

1.2. Special types

Ok, so far we've understood that all primitive values already exist, and that writing 2 or hello in our code always "summons" the same number or string value.

Special types, however, behave very differently, and allow us to generate our own values. They are only two special types in JavaScript:

- Objects =>

{firstname: 'John', lastname: 'Doe'} - Functions =>

function hello() { console.log('hello') }

When writing {} or () => {}, it always create a brand new different value:

let banana = {}

let apple = {}

console.log(banana === apple) // ❌ false: they are different values !

If we take a look back at our first example:

// Create a brand new object with properties firstname and lastname

// pointing to the already existing strings "John" and "Doe"

const userA = {firstname: 'John', lastname: 'Doe'}

// Again, create a brand new object with properties firstname and lastname

// pointing to the already existing strings "John" and "Doe"

const userB = {firstname: 'John', lastname: 'Doe'}

// userA and userB are totally different objects

if (userA === userB) {

console.log('Both users are the same')

} else {

// ...so they are "different", even though their properties are equal

console.log('Users A and B are different')

}

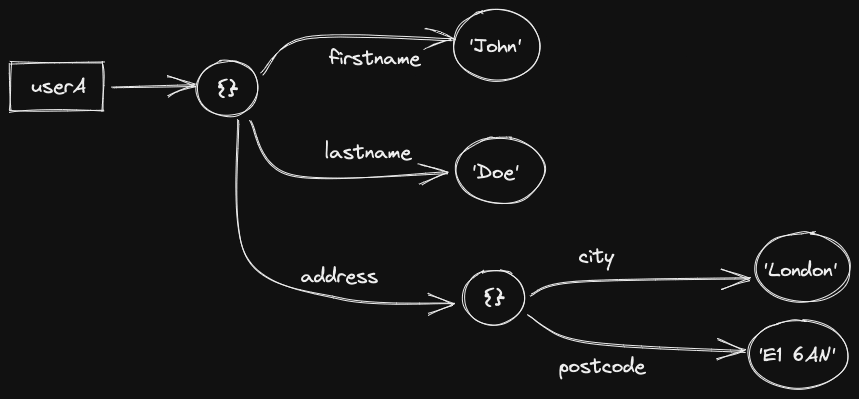

userA and userB both point to a brand new object. Each object has a property firstname pointing to the one and only string value 'John', and a property lastname pointing to the one and only string value Doe. Here is a sketch of the variables userA and userB:

Properties of an object can be seen as wires pointing to a value. Nothing more, nothing less. They can either point to primitive values, as is the case here, or they can also point to special types like other objects:

2. Types of equality

In JavaScript, they are several kinds of equality:

- Strict Equality:

a === b(triple equals). - Loose Equality:

a == b(double equals). - Same Value Equality:

Object.is(a, b)

The rules of loose equality (also called "abstract equality") can be confusing, which is why many coding standards nowadays prohibit its use altogether.

Nowadays web coding standards mainly use strict equality and same value equality. They behave mostly the same way, except two rare cases:

-

NaN === NaNisfalse, although they are the same value -

-0 === 0and0 === -0are true, although they are different values.

Fun fact: Despite Object in the method name,

Object.isis not specific to objects. It can compare any two values, whether they are objects or not!

console.log(Object.is(2, 2)) // ✅ true

3. Conclusion

🌯 Let's wrap things up: so far we've learned that primitive values in JavaScript can't be created, they already exist. Special type values, however, like objects or functions, are always generated to give us brand new values, which is why two objects or functions will never be strictly the same (===).

Objects have properties, which can be seen as wires pointing to primitive values, or to other objects. This can be confusing if two objects have properties pointing to the same values, like the ones in our very first example at the top: they may look the same, but they are indeed two different objects.

To build a reliable mental model around this, it's particularly useful to visualize wires going from our variables and pointing to values in the JavaScript universe. I have used Excalidraw to sketch the diagrams for this blog post, and I highly encourage you to try it out on real-world scenarios to sharpen your mental model.

This post was inspired by the fabulous Just JavaScript Course by Dan Abramov, illustrated by Maggie Appleton. The course is really affordable and definitely worth spending some time on.

4. Bonus: React hook dependencies

If you're using React, it is very likely that you have to manage useEffect dependencies here and then. Understanding equality of values is particularly important in this case, because as I mentioned previously on my post Master the art of React.useEffect:

React relies on value stability for

useEffectdependencies

This means that if you have a dependency which value isn't stable from a render to another, your useEffect will in fact run on every render. React will see that one of the dependencies has changed, so it will run the useEffect to synchronize with it. Here is a (really contrived) example to illustrate my point:

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(10)

const alertCountOver = () => console.log('Count is too high !');

React.useEffect(() => {

console.log('running check on count value')

if (count > 100) {

alertCountOver()

}

}, [count, alertCountOver])

What we want in this situation is our useEffect to run every time count changes. Because we use the alertCountOver function in the useEffect, our dear ESLint plugin has told us we should include it in our dependencies array.

The problem is: alertCountOver isn't stable! In fact, every time this component will render, the alertCountOver variable is assigned to a brand new function, so its value will always be different from previous renders. This results in our useEffect running on every render. Whoops 🥴

This is why understanding the difference between primitive values, special types values and how they behave when performing strict equalities is crucial here.

There are two possible solutions in our case:

- Extract the function

alertCountOveroutside of our component's body: this way the assignment will only occur once, and the value will become stable.

// ✅ This is fine

const alertCountOver = () => console.log('Count is too high !');

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(10)

React.useEffect(() => {

if (count > 100) {

alertCountOver()

}

}, [count, alertCountOver])

return (

// ...

)

}

-

Memoize the value of

alertCountOverto make it stable:

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(10)

// ✅ This is fine

const alertCountOver = React.useCallback(

() => console.log('Count is too high !')

, []);

React.useEffect(() => {

if (count > 100) {

alertCountOver()

}

}, [count, alertCountOver])

return (

// ...

)

}

To learn more about memoization in React, check out this blog post by Kent C. Dodds

That's all for today's breakfast folks. If you liked this post, feel free to share it with your friends/colleagues and leave your thoughts in the comments!

Have a fantastic day,

With 🧡, Yohann

Top comments (0)