I found the first mention of Kubernetes in computer science!!

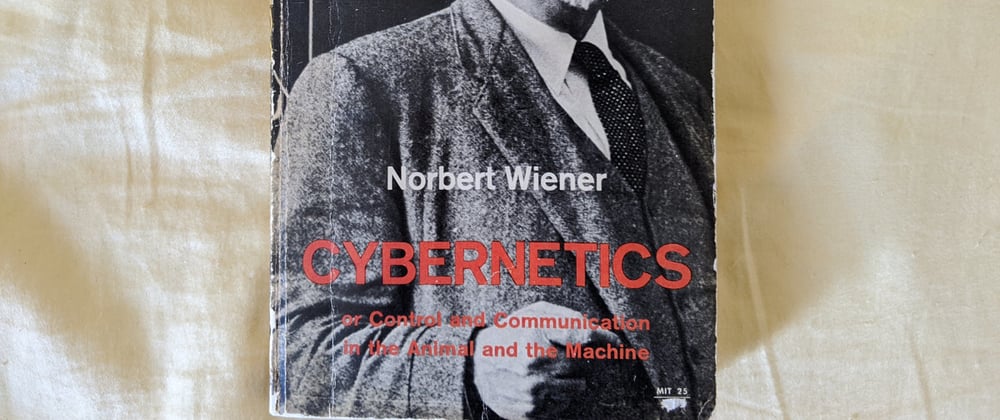

It comes from a book. "Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and Machine" by Norbert Wiener. Originally published in 1948. (Yes, even in 1948, non-fiction book titles abused the colon.)

The book has its own Wikipedia page. So many people read it that he published a sequel!

It's surprisingly hard to find. The New York Public Library has two copies offsite, only available on advanced request. The Brooklyn Public Library has zero copies.

I like to imagine I have the only physical copy in pandemic-lockdown New York City! Because right before the lockdown, I borrowed the 1961 edition from a science historian. And she hasn't asked for it back yet 😬.

In the book, Wiener tries to come up with a name for his new field. He writes: "All the existing teminology has too heavy a bias [...] we have been forced to coin at least one artificial neo-Greek expression to fill the gap."

He suggests "Cybernetics," from the Greek word χυβερνήτης, also pronounced "Kubernetes":

Why Cybernetics?

You may think that this is just a pointy-headed in-joke to make the rest of us feel dumb.

But it's actually a very relevant pointy-headed in-joke that only incidentally makes the rest of us feel dumb!

When Wiener published "Cybernetics," the dominant model of computing was finite automata and Turing machines. These are systems that take inputs at the start and produce outputs at the end.

Wiener points out that there are two problems with this model:

1) In any system with lots of closely coupled inputs, we need statistical models to handle the complexity. In chapter one, he compares astronomy versus meteorology. We can count how many stars there are, and can capture the interaction between stars with simple formulas. But in meteorology, there are simply too many particles and the interactions between them are too complex.

2) Information is distributed over time. We can use the time component to learn which inputs cause which outputs, and build feedback loops.

Wiener argues that if computer science does a better job embracing complex statistical systems and time-based feedback loops, we'll be able to better understand lots of non-mechanical systems, like biology and sociology.

The book gets very galaxy-brained to be honest, from "How do we build better thermostats?" to "Could this help us find a cure for Parkinson's disease?"

What Does That Mean For How We Build Systems?

Once you understand this parallel, you see it everywhere!

Consider Kubernetes. Before Kubernetes, you may have had a deploy script. That deploy script worked like a finite automata: look at some inputs, then deploy a server.

One of the key insights of Kubernetes is that when you're working with multiple servers with close coupling, this isn't enough. You need a system with runtime feedback loops to handle the runtime dependencies between servers.

I think this insight applies to developer tools as well. From Make in the 70s to Bazel today, build systems are still stuck in a world of finite automata, mapping inputs to outputs.

But the servers we're building have closely coupled runtime dependencies! Multi-service developer tools need runtime feedback loops as well.

Originally published on the Tilt Blog.

Top comments (0)