Before we get started

If you're a beginner android dev: don't drop this knowledge in an android interview 😬 IMO most interviewers today (August 2021) will expect to hear about clean architecture, stateless usecases, coroutines, flow, and maybe jetpack compose.

If you've been around long enough to remember android before reactive streams (perhaps not very fondly!): I ask you to keep an open mind, we have nearly 10 years more experience than we had back then, the classic mistakes are much easier to avoid this time around.

For everyone else: Reactive streams has been used in android architectures since a few years after android was first released (initially just as a way to replace AsyncTask - google's clunky way of creating a thread). It's completely understandable if you thought there was no other reasonable way to write an android app, but it turns out there is...

The current state of play

We're going to consider clean architecture specifically here, but this applies to any android architecture where you have a view layer reacting to state changes.

Many Android implementations of clean architecture use reactive streams (usually RxJava or Kotlin Flow) to connect architectural layers together.

Over the years, I've come to believe that reactive streams is completely the wrong abstraction for architecting android applications and implementing non-trivial reactive UIs. Please note, I'm not saying you shouldn't use reactive streams in android! - there are plenty of good reasons to use reactive streams in general.

Reactive Streams

Let's first back up a little. Reactive Streams could just as well have been called Observable Streams, and you can consider it a combination of two concepts:

- Observers (tell me whenever you’ve changed)

- Streams (data and operators like .map .filter etc)

For some specific use cases: handling streams of changing data, which you want to process on various threads (like the raw output of an IoT device for example) reactive streams is a natural fit. The needs of most android app architectures however tend to be a little more along the lines of:

- connect to a network to download discreet pieces of data (always on an IO thread)

- update a UI based on some change of state (always on the UI thread)

You certainly can treat everything as a reactive stream if you wish, and if parts of your app actually aren’t a great match for reactive streams, you can just have your functions return a Single<Whatever> anyway. Regular code that touches reactive streams often gets "reactive-streamified" like this (even code that isn’t, and has no need to be, reactive in the first place).

Anyway, it’s entirely possible to treat these two concepts separately. We can consider a piece of code’s observable nature separate to the data that actually changed (I explain how below). This means your function signatures don’t have to change, you can continue returning a Boolean if that’s what you need to do, and Observable<Somethings> won’t slowly spread throughout your code base.

Back to current architectures

The typical android clean architecture example you'll find on the internet is also only reactive in a fairly trivial way: UI triggers a request -> then receives a response, sometimes with updates (essentially a callback).

Once you include reacting to things which aren't triggered by the UI though (like in real apps), things get complicated. Let's say you want your UI to react to a change of network status, or an external accessory being plugged in, or a notification being received to the device (or all of these at the same time). Add Android's infamous lifecycle into the mix with its self-destroying views, and the abstraction starts to look a little shakey.

Here, caching and memory references start to be a big problem for android (whereas they might not be such a problem on the server side).

The typical solution to this is to turn everything into a reactive stream, and with enough RxJava operators you can of course fix all the caching and memory reference problems - but these are problems that only exist because of choosing an inappropriate abstraction in the first place. Remove Reactive Streams from your android architecture and you remove the problems

Enough talking, show me the money

Here's the UI from a sample clean architecture app (the code is on github). It displays various fake weather data fetched from the internet, downloaded on a real network connection.

I'd recommend you clone the repo and play with the app on a device, it's hard to get a feel of just how dynamic the screen is from a screen shot.

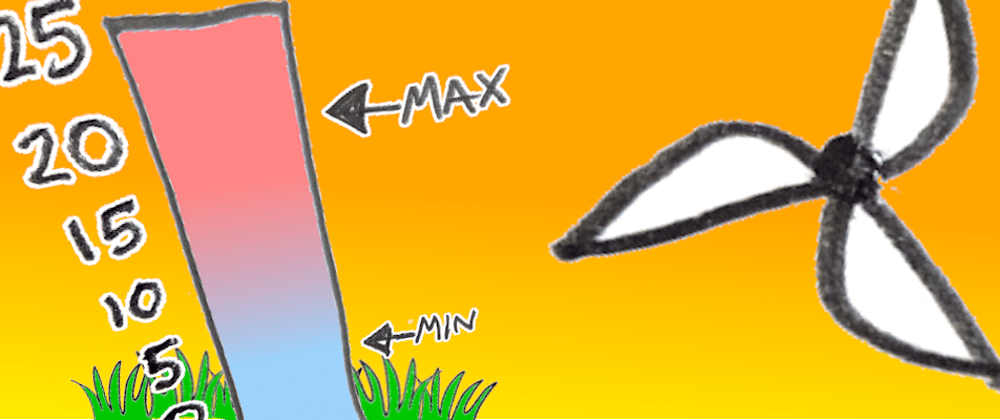

The view is divided into two halves so you can see how it works, the graphics on the left hand side are completely driven by the data on the right hand side. So for example, the MAX and MIN temperature indicators are positioned according to the maxTempC and minTempC states.

DashboardViewState(

weather=WeatherViewState(

maxTempC=16,

minTempC=0,

windSpeedKmpH=33,

pollenLevel=MEDIUM

),

autoRefresh=AutoRefreshViewState(

timeElapsedPcent=0.0,

autoRefreshing=false

),

errorResolution=null,

isUpdating=false

)

Any time the state changes, the UI updates itself automatically. If the user gets back from making a phone call, or rotates their screen, the UI just refreshes whatever state is provided. Any animations are fired on state changes (for instance when the temperature values change)

Because all the heavy lifting is being done elsewhere, the view code is thin: about 100 lines (50 if we remove the animations). This makes it easy to maintain or change.

The ViewModel which creates this immutable view state is observing two main things: a WeatherModel and a RefreshModel (if that sounds unfamiliar to you, you can think of these models as ViewModels that have application level scope, or see what wikipedia has to say about domain models).

Even though this app is still quite simple, it does more than the typical "trigger a request -> receive a response" sample code. Some of the changes it's observing don't directly originate from the the UI. Despite this complication, what's missing from the view model here is most of the boiler plate associated with reactive streams. Rotating the screen also doesn't cause any additional network requests to be fired, it doesn't require a dedicated caching strategy either because the state of the models in the domain layer hasn't changed (this tracks reality much closer - why would the weather state need to be re-queried as a result of a screen rotation anyway?).

What's a bit surprising for people who come across this technique for the first time, is that the benefits become even more apparent as more things are observed (let's say we also wanted to observe a NetworkAvailabilityModel and a NotificationModel, it would be an extra line for each in the ViewModel, and still no memory leaks).

So how does it work then?

Basically, the observer pattern.

In this sample, the observable pattern is implemented with a library (fore) but it's important to realise that the actual code is fairly simple, it boils down to a list of observers (usually the observers are in the UI layer somewhere, added and removed in line with the view lifecycle) that implement this interface:

interface Observer {

fun somethingChanged()

}

The only requirement back in the domain layer, is that all observable models need to call notifyObservers() whenever their state has changed.

These notifications get fired either on the UI thread (which is what you want when updating your UI) or the current thread (which is what you want during a unit test).

We hinted at it earlier, but the key innovation here is that we have separated a piece of code’s observable nature from the data that actually changed.

This means we no longer have multiple observable APIs to deal with such as an Observable<WeatherState>, an Observable<RefreshState> and an Observable<NetworkState> (or Flow<WeatherState>, Flow<RefreshState> Flow<NetworkState>, etc.) Everything is observable in exactly the same way: something changed, or it didn't.

That turns out to be unbelievably helpful when removing boiler plate and driving complex reactive UIs (there are some robustness wins too). That level of simplicity won't be any good for processing streams of IoT data - that we can do using Flow, but for tying together android architectural layers in a large complex reactive app it's pretty unbeatable.

The full app is on github

Latest comments (0)