Original article here: https://dashbird.io/blog/complete-guide-lambda-triggers-design-patterns-part-2/

This is part of a series of articles discussing strategies to implement serverless architectural design patterns. We continue to follow this literature review. Although we use AWS serverless services to illustrate concepts, they can be applied in different cloud providers.

In the previous article (Part 1) we covered the Aggregator and Data Lake patterns. In today's article, we'll continue in the Orchestration & Aggregation category covering the Fan-in/Fan-out and Queue-based load leveling.

We previously explored these concepts in Crash Course on Fan-out & Fan-in with AWS Lambda and Why Serverless Apps Fail and How to Design Resilient Architectures, in case you'd like to dig deeper into some more examples.

Pattern: Fan-in / Fan-out

Purpose

Accomplish tasks that are too big or too slow for a single serverless function to handle.

Solutions

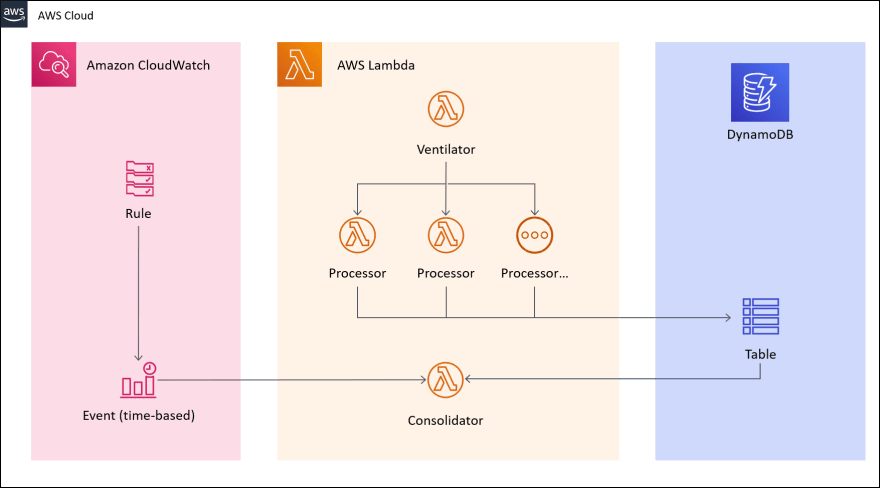

We have basically four major steps in a Fan-in/Fan-out architecture:

- Source of task: everything starts with a big task or a large list of tasks

- Ventilator: this is the entry point of the task and where the "Fan-out" process starts

- Processing: where tasks are actually accomplished

- Consolidation: brings together results from all task processing (a.k.a. "Fan-in")

We'll cover possible solutions for each of these stages below. In some cases, we use examples to illustrate our points. They are hypothetical scenarios and not necessarily an implementation recommendation for any particular case.

Task Source

Tasks could literally come from any possible AWS Lambda triggers, either synchronous or asynchronous. This includes traditional invoke API calls, or integrations with API Gateway, DynamoDB Streams, etc.

For tasks that involve processing large amounts of data, it's common to use integrations, since the invocation payload size limits are relatively low (up to 256 KB - 6 MB). For example, to process a 1 GB video file, it can first be stored in S3. The S3 PUT operation can automatically trigger a Lambda function. It doesn't violate Lambda limits because the invocation only provides the S3 object key. The Lambda function can then GET the file from S3 for processing.

AWS also recently added support for EFS (Elastic File System) within Lambda functions, which is an alternative to S3 for storing tasks with underlying large amounts of information. The criteria to choose between both services go beyond the purposes of our article.

Ventilator

This is where the Fan-out process really starts. An entry-point Lambda function receives a big task (or a large list of tasks) and is responsible for handling the distribution to multiple processors. Tasks can be distributed individually or grouped in small packs.

In the example of a 1 GB video file, let's say we need to perform machine learning analysis on video frames, or extract audio from the video. The Ventilator function could break the video down in 200 pieces of 5 MB. Each of these smaller video sections would be supplied to an external API, a cluster of servers, or even a second Lambda function to conduct proper analysis.

This is obviously based on the premise that breaking the video apart is extremely faster than performing the analysis we are interested in.

Processing

The 200 Fan-out requests coming from the Ventilator can be dispatched concurrently to multiple processors.

If it takes, let's say, 1 minute to process every 1 MB of video file, the entire task can be accomplished in 5 minutes (1 minute * 5 MB/section). If the entire video was to be processed sequentially in a single node, it would take 1,000 minutes (or +16 hours). Clearly not possible in Lambda, due to timeout limitations.

You might think this will also reduce total costs, since Processor Lambdas could be configured with much less memory than what the large task requires. But in most Fan-in / Fan-out use cases, the workload is CPU-bound. Reducing memory size will also reduce CPU power, which in turns increases processing time. Since Lambda is billed not only by memory size, but also per duration, the gains in lower memory allocation can be offset by the longer duration.

To learn more about this, I recommend reading How to Optimize Lambda Memory and CPU and Lower Your AWS Lambda Bill by Increasing Memory Size.

Consolidation

In some cases, it will be necessary to bring results from all processors together. Since each Fan-out process will probably run independently and asynchronously, it's difficult to coordinate the results delivery without an intermediary storage mechanism.

For that we can use:

- Queues, Topics or Event Bridges

- Stream processors

- Databases or Datastores

In the AWS ecosystem, for the first group we have SQS (queue), SNS (topics) and EventBridge. In the second, Kinesis has different flavors depending on what type of data and requirements we have. Finally, in the third group there are S3 (object storage), Aurora Serverless (relational database) and DynamoDB (key-value store). Again, choosing what suits better each use case is beyond the scope of our current discussion.

Each of these services can act as a temporary storage for processing results. A third Lambda function, which we'll call Consolidator, can later pick up all the results and assemble them together in a coherent way for the task at hand.

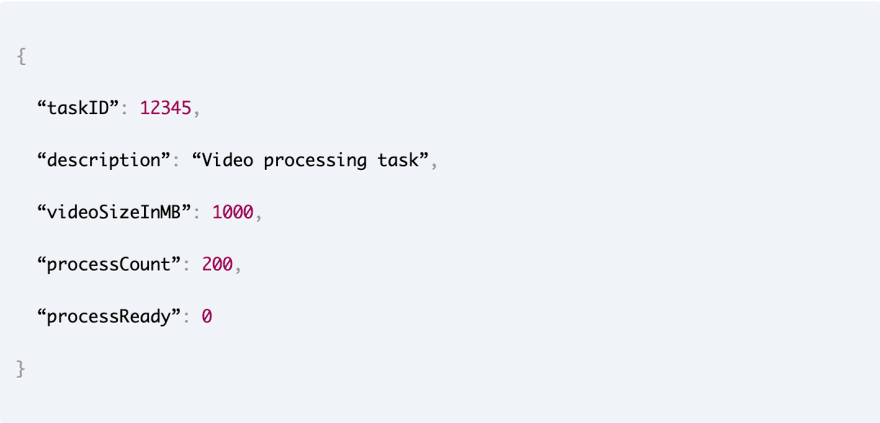

But how does the Consolidator know when everything is ready? One approach is having the ventilator storing a task summary in a DynamoDB table, for example. It could store an item such as this:

Each processor increments the processReady integer when its task is finished. Since DynamoDB supports atomic incrementing, this operation is safe for our use case.

The Consolidator function can be invoked on a scheduled basis, using CloudWatch Rules, to check whether processReady == processCount. Or we can also use DynamoDB Streams to automatically invoke the Consolidator upon item update (which may not be efficient, since the Consolidator will have to ignore 199 invocations out of 200).

One disadvantage of this architecture regards monitoring and debugging issues. A good practice would be to generate a unique correlationID in the Ventilator, which is passed to each Processor. All Lambda functions should log the same correlationID, this way it's possible to track down every request associated with a single Fan-in/Fan-out process.

Monitoring services that are tailored to Serverless also allows us to create “projects” representing multiple Lambdas, which simplifies issue tracking and resolution on distributed architectures such as Fan-in/Fan-out.

Pattern: Queue-based load leveling

Purpose

Decouple highly variable workloads from downstream resources with expensive or inelastic behavior.

For example: consider an API Endpoint, whose incoming data is processed by a Lambda function and stored in a DynamoDB table with a Provisioned capacity mode. The concurrency level of the API is usually low, but at some points, during short and unpredictable periods of time, it may spike to 10x to 15x higher. DynamoDB auto-scale usually can't cope with the rapid pace of demand increase, which leads to ProvisionedThroughputExceededException.

Solutions

The Queue-based Load Leveling pattern is a great candidate to solve this type of problem. It is highly recommended for workloads that are:

- Write-intensive

- Tolerant to an eventually-consistent data model

- Highly variable

- Subject to unpredictable spikes in demand

Implementing the solution is straightforward. In the example above, instead of having the Lambda function directly storing data in DynamoDB, it pushes the data to a Queue first. It responds with a 200-Ok to the consumer, even though the data hasn't reached the final destination (DynamoDB) yet.

A second Lambda function is responsible for polling messages from the Queue in a predetermined concurrency level that is aligned with the Provisioned Capacity allocated to the DynamoDB table.

Risk Mitigation

The risks associated with this pattern are mainly data consistency and loss of information.

Having a Queue in front of DynamoDB means the data is never “committed” to the datastore immediately after the API client submits it. If the client write and read right after, it might still get stale data from DynamoDB. This pattern is only recommended in scenarios where this is not an issue.

During peaks, the Queue may grow and information can be lost if we don't take necessary precautions. Messages will have a retention period, after which they'll be deleted by the Queue, even if not read yet by the second Lambda.

To avoid this situation, there are three areas of caution:

- Enable centralized monitoring of your Inventory of queues to receive alerts about the ones growing too rapidly before messages are at risk of being lost

- Set a retention period that leaves comfortable time for the second Lambda to catch up in the event of unexpected long spikes

- Configure a Dead Letter Queue to give an extra room for processing - make sure to observe a caveat when setting an appropriate retention period for this additional queue

Important considerations

Read-intensive workloads can't benefit from Queue-based load leveling, basically because we must access the downstream resource to retrieve the data needed by the consumer. Reserve this pattern for write-intensive endpoints.

As discussed before, Queue-based is not recommended for systems where strong data consistency is expected.

The pattern can only deliver good value in scenarios where demand is highly variable, with spiky and unpredictable behavior. If your application has steady and predictable demand, it's better to adjust your downstream resources to it. In case of DynamoDB, the auto-scale feature might be enough, or maybe increasing the Provisioned Throughput would be recommended.

Wrapping up

In the next articles, we'll discuss more patterns around Availability, Event-Management, Communication and Authorization. Make sure to subscribe and be notified if you'd like to follow up.

Implementing a well-architected serverless application is not an easy fit. To support you on that Journey, Dashbird launched the first serverless Insights engine. It runs live checks of your infrastructure and cross-references it against industry best practices to emit early signs preventing failures and indicating areas that can benefit from an architectural improvement. Test the service with a free account today, no credit card required.

Top comments (0)